Roman soldier’s 1,900-year-old payslip uncovered in Masada

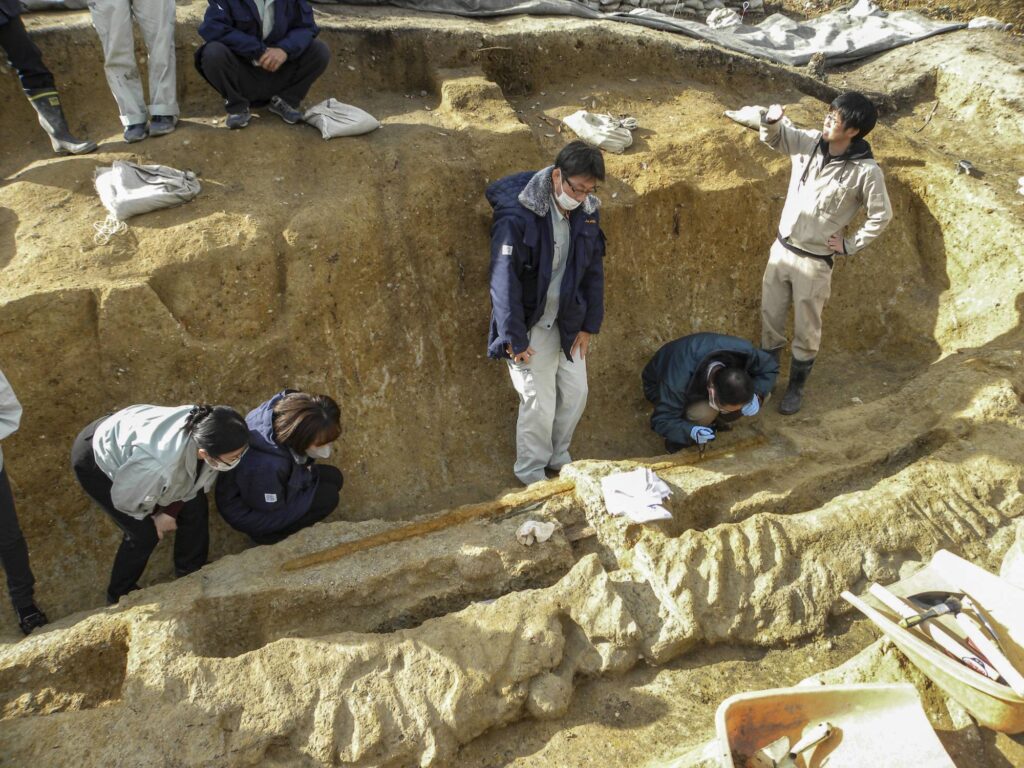

During excavations at Masada, archaeologists from the Israel Antiquities (IAA) uncovered a papyrus payslip dated to 72 BC belonging to a Roman soldier.

Masada is a rugged crag in the Judean Desert overlooking the Dead Sea. Herod, the first-century BCE Judean king best known for constructing Jerusalem’s Temple Mount complex, built a fortress and palace on the mountain.

Jewish rebels entrenched themselves at Masada a century later, from 66 to 74 CE, during the Jewish Revolt against Rome. A Roman army besieged the last holdouts nearly four years after the fall of Jerusalem.

The only historical account of the conflict is Josephus Flavius, who claims that the Jewish rebels all committed mass suicide before Roman troops stormed the battlements. However, archaeologists dispute that account’s historical accuracy.

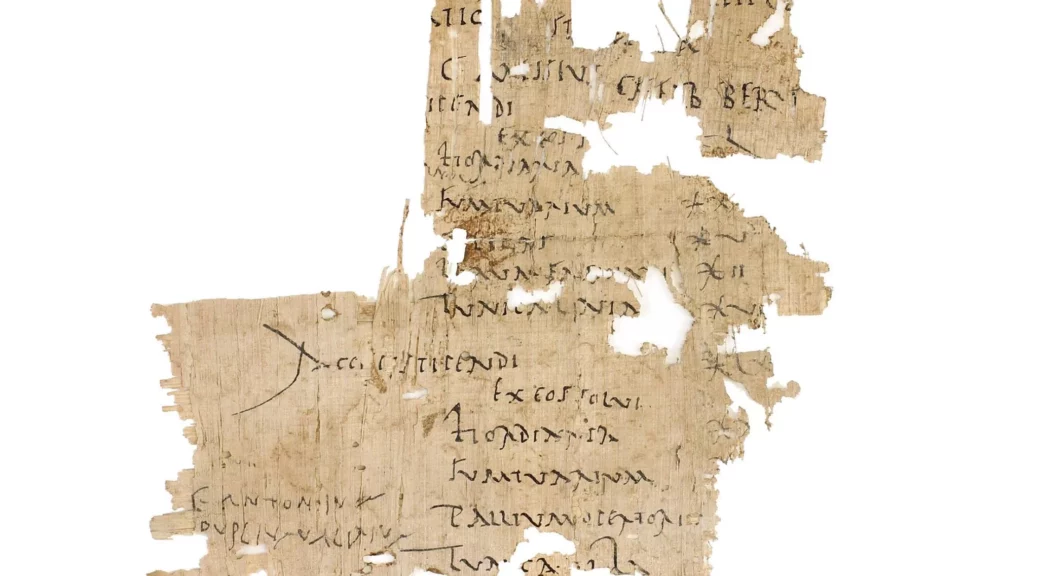

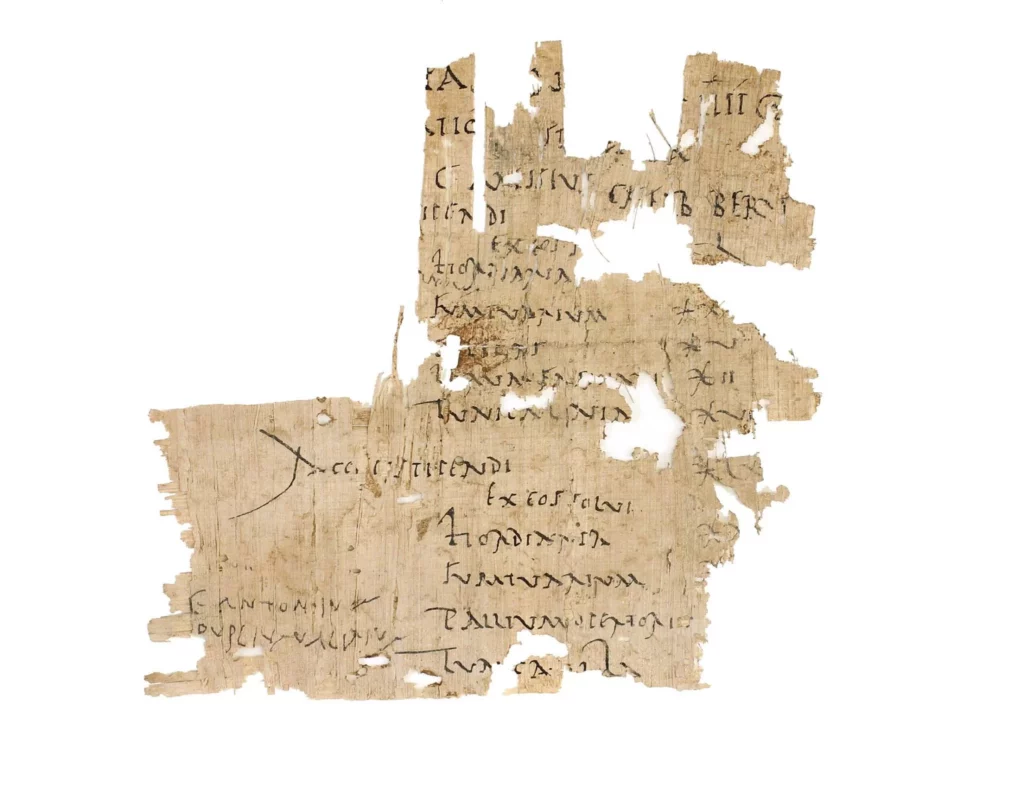

The IAA discovered a detailed military paycheck (one of only three legionary paychecks discovered throughout the Roman Empire) issued to a Roman legionary soldier during the First Jewish-Roman War in AD 72.

The paycheck is one of 14 Latin scrolls found at Masada by archaeologists – 13 of which was written on papyrus, and one on parchment paper.

Although the papyrus was damaged over time and therefore very fragmentary, it contains valuable information about the management of the Roman army and the status of the soldiers.

The document provides a detailed summary of a Roman soldier’s salary over two pay periods (out of three he would receive annually), including the various deductions that he was charged. The army supplied the soldiers with basic equipment, but, as today, some soldiers chose to add and upgrade their equipment.

“This soldier’s paycheck included deductions for boots and a linen tunic, and even for barley fodder for his horse,” says Dr. Oren Ableman, senior curator-researcher at the Israel Antiquities Authority Dead Sea Scrolls Unit.

“Surprisingly, the details indicate that the deductions almost exceeded the soldier’s salary. Whilst this document provides only a glimpse into a single soldier’s expenses in a specific year, it is clear that in the light of the nature and risks of the job, the soldiers did not stay in the army only for the salary.

According to Dr. Ableman, “The soldiers may have been allowed to loot on military campaigns. Other possible suggestions arise from reviewing the different historical texts preserved in the Israel Antiquities Authority Dead Sea Scrolls Laboratory.

For example, a document discovered in the Cave of Letters in Nahal Hever from the time of the Bar Kokhba Revolt (132–135 CE) sheds some light on some side hustles Roman soldiers used to earn extra cash.

This document is a loan deed signed between a Roman soldier and a Jewish resident, the soldier charging the resident with interest higher than was legal.

This document reinforces the understanding that the Roman soldiers’ salaries may have been augmented by additional sources of income, making service in the Roman army far more lucrative.”