A trove of 13,000 Artifacts Sheds Light on Enigmatic Chinese Civilization

For hundreds of years, the Sanxingdui culture flourished in what is now southwest China, producing ornate bronze masks and precious wares before vanishing abruptly around 1100 or 1200 B.C.E.

Believed to be part of the broader Shu state, the civilization continues to fascinate more than 3,000 years after its demise. As state-run news agency Xinhua reports, a trove of 13,000 artefacts unearthed at the Sanxingdui Ruins site over the past two years is poised to offer new insights into the mysterious Bronze Age culture.

Found in six sacrificial pits, according to China Daily’s Wang Kaihao, the cache includes 1,238 bronze wares, 543 gold artefacts and 565 jade objects.

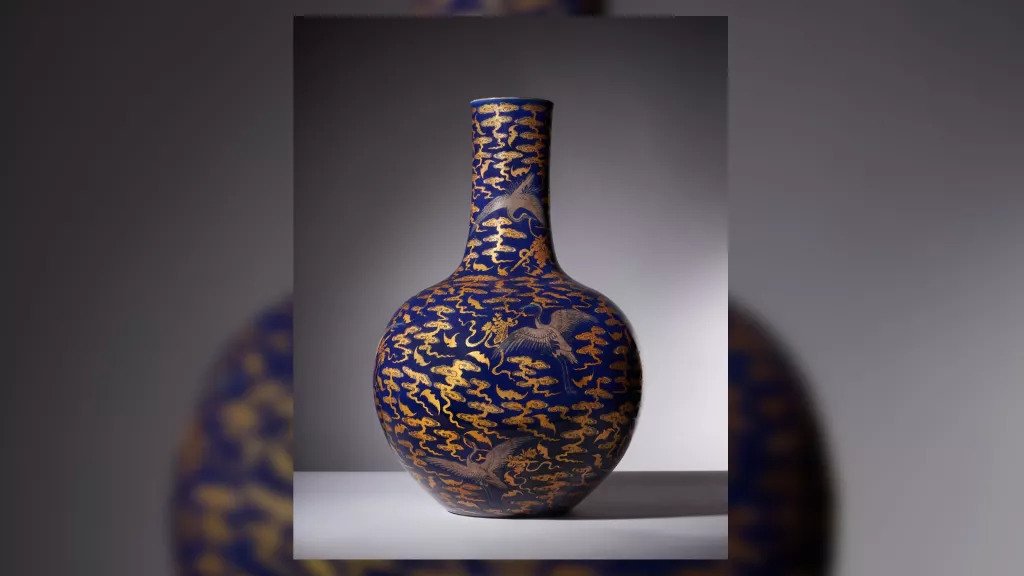

Among the highlights of the discovery is a bronze box with a tortoise-shaped lid, dragonhead handles and bronze ribbons. Green jade is tucked inside the container, which appears to have once been wrapped in silk.

“It would not be an exaggeration to say that the vessel is one of its kind, given its distinctive shape, fine craftsmanship and ingenious design,” Li Haichao, an archaeologist at Sichuan University, tells Xinhua. “Although we do not know what this vessel was used for, we can assume that ancient people treasured it.”

Other key finds include a bronze sacrificial altar, a giant bronze mask, and a bronze statue with a human head and a snake’s body. Per the Global Times’ Ji Yuqiao, the hybrid figure rests its hands on a lei drinking vessel; another type of vessel known as a zun is painted on the statue’s head in vermillion hues.

The sculpture’s blend of artistic styles reflects the “early exchange and integration of Chinese civilization,” says Ran Honglin, a researcher at the Sichuan Provincial Cultural Relics and Archaeology Research Institute, to Xinhua. It’s human and snake components are typical of the Shu state, while the lei is more commonly associated with the pre-Western Zhou Dynasty. The zun is historically found in the Zhongyuan region.

“These three factors are now blended into one artefact, which demonstrates that Sanxingdui is an important part of Chinese civilization,” Ran adds.

According to an official government FAQ, a farmer stumbled onto the Sanxingdui Ruins in 1929. The first archaeological excavation at the site took place in 1934, but work soon drew to a halt amid the political tumult of the mid-20th century.

It was only in 1986 that scholars recognized the significance of the ruins: As Live Science’s Tia Ghose wrote in 2014, archaeologists found two pits filled with 1,000 artefacts, including eight-foot-tall bronze sculptures whose artistry points to an “impressive technical ability that was present nowhere else in the world at the time.” Because the objects were broken or burned before burial, experts concluded that they’d been placed in the pits as part of a sacrificial ritual.

In addition to the towering figurines, excavators discovered oversized bronze masks with exaggerated facial features. Measuring around three feet wide, the masks share several key characteristics, per the Saxingdui Museum: “knife-shaped eyebrows, protruding eyes in [a] triangle shape, big stretching ears, snub nose and fine mouth.” Experts posit that the masks may have memorialized their creators’ ancestors or gods.

No written records or human remains associated with the Sanxingdui survive today, reports Kathleen Magramo for CNN. But scholars generally agree that the culture was part of the kingdom of Shu, which thrived on the Chengdu Plain until its defeat by the state of Qin in 316 B.C.E. The exact reasons for the Sanxingdui’s decline are unknown, but theories abound, with earthquakes, war and flooding all proposed as possible explanations.

Based on the discovery of similar artefacts at Jinsha, about 30 miles away from the Sanxingdui Ruins, some archaeologists argue that the Sanxingdui moved to Jinsha and rebuilt their community there.

Between 2020 and 2022, a renewed slate of excavations uncovered six additional pits at the Sanxingdui site. Last year, archaeologists revealed fragments of a gold mask, traces of silk, bronzeware adorned with depictions of animals, ivory carvings and other artefacts.

The current round of excavations is slated to conclude in October. As Ran tells the Global Times, “The number of unearthed cultural relics will keep increasing with further work.”