Parasite eggs in old toilet came from pork eaten 1,300 years ago

Nara Prefecture–Denizens of the Asuka Period (592-710) feasted on pork and may have done so routinely, archaeologists deduced from parasite eggs excavated from a toilet structure found in the ruins of the ancient capital of Fujiwarakyo.

The eggs, which serve as scientific evidence of pork consumption because humans are infected with parasites after eating undercooked pork, are one of the oldest findings in the country, researchers from the Archaeological Institute of Kashihara, Nara Prefecture, reported.

It is possible that immigrants from the Chinese continent ate pork regularly, they added.

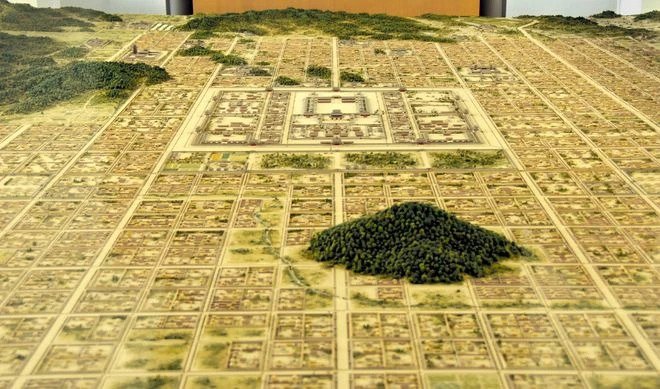

The institute excavated the ruins of Fujiwarakyo, which served as the imperial capital between 694 and 710 in Sakurai, also in the prefecture, in the year ending in March 2019. It found a toilet structure in the northeast of the remains of the Fujiwara no Miya palace, the centerpiece of the capital.

Masaaki Kanehara, a professor of environmental archaeology at Nara University of Education who also serves as a collaborative researcher at the institute, and his wife, Masako, head director of the Cultural Assets Scientific Research Center, a general incorporated association, analyzed soil samples.

According to the researchers, there were five egg shells found in the soil. The eggs were apparently laid by a parasite known as a pork tapeworm, which infects humans when they eat pork.

Although bones of boars or pigs possibly raised by humans had been found when the institute conducted a survey at Fujiwarakyo in the year ending in March 2001, no pork tapeworm eggs were discovered at the time.

Similar parasite eggs had also been found in toilet structures of the ruins of Korokan in Fukuoka, which is referred to as the “ancient guest palace,” and Akita Castle in Akita. Both structures apparently date to the Nara Period (710-784), meaning that the eggs were younger than those found at Fujiwarakyo.

Previously, what appeared to be pig bones were found from an archaeological site dating back to the Yayoi Period (c. 1000 B.C.-250 A.D.). But parasite eggs provide more direct evidence for pork consumption.

Professor Kanehara said that the parasite eggs were excreted by humans after they ate undercooked pork. It is also possible that they ate pork on a routine basis because the eggs were found in the remains of the toilet facility used on a daily basis.

In the late seventh century, just before Fujiwarakyo, believed to be Japan’s first full-scale capital laid out in a grid pattern on the ancient Chinese model, was built, the Baekje and Goguryeo kingdoms in the Korean Peninsula both were conquered. It is thought that many of the emigrants fled to Japan.

The parasite eggs show that people who came from the food cultures of the Chinese continent and Korean Peninsula lived in Fujiwarakyo, the institute said in its report released in the spring.

“(The parasite eggs) are important pieces of information to shed light on a meat-eating culture in the history of eating habits in Japan because many facts about pig breeding and the regular consumption of pork at the time remain unclear,” said Masashi Maruyama, an associate professor of zooarchaeology at Tokai University’s School of Marine Science and Technology who studies the history between humans and animals from the standpoint of archaeology.

“Unlike cows and horses, pigs don’t require pastures. It is quite possible that they were bred inside Fujiwarakyo.”

‘CIRCUMSTANTIAL EVIDENCE’ OF PORK CONSUMPTION

Various pieces of “circumstantial evidence” indicate that pork had also been consumed even in older times.

Excavated from a Yayoi Period site in Oita was what appeared to be a pig skull. With similar bones also having been unearthed at other Yayoi Period ruins, they are collectively referred to as the “Yayoi pig” to differentiate them from wild boars. It is possible that there were people who raised pigs and ate them.

Meanwhile, the word “ikainotsu” is mentioned in one section in “Nihon Shoki” (The Chronicles of Japan), a book of classical Japanese history compiled in the eighth century, which is dedicated to the period of time when Emperor Nintoku reigned. It suggests that there were people whose jobs were to breed boars.

Another entry shows that the meat from cows, horses, dogs, monkeys and chickens were forbidden from consumption in 675, just before the capital was relocated to Fujiwarakyo. However, there are no direct mentions of pigs and boars. The practice of eating animal meat became increasingly shunned with the spread of Buddhism, which prohibits killing.

However, according to Maruyama, the meat of pigs and boars were eaten in Edo (present-day Tokyo), Osaka, Hakata and Nagasaki’s Dejima island, on which the Dutch trading post was located, in the Edo Period (1603-1867). Animal bones were also excavated from historical sites in each region.

The Tokyo-based Japan Pork Producers Association states on its website that pig and boar breeding became widespread in Japan after techniques were presumably brought into Japan by immigrants from the Chinese continent and Korean Peninsula between 200 and 699.

But it makes it unclear as to exactly when livestock breeding began, citing there are varying opinions.