Mayan DISCOVERY: How find in 2,000-year-old city ‘reveals story of creation’

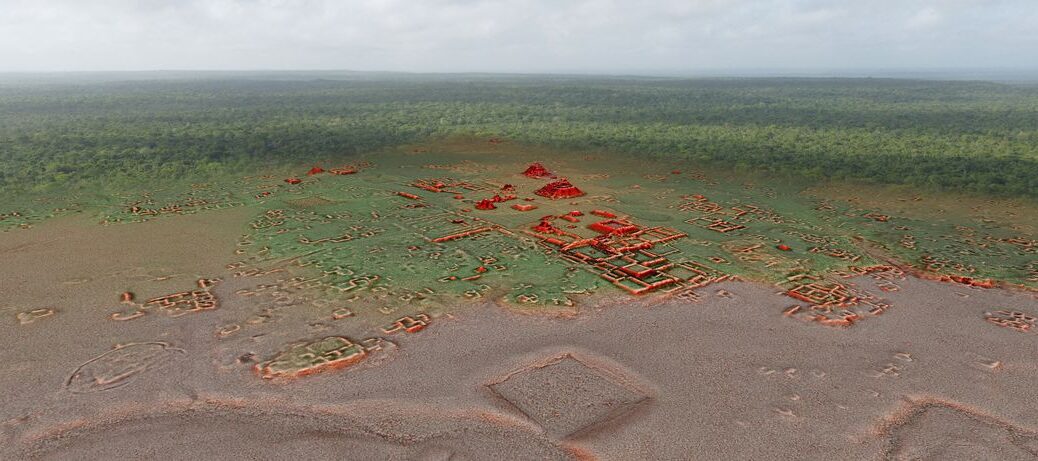

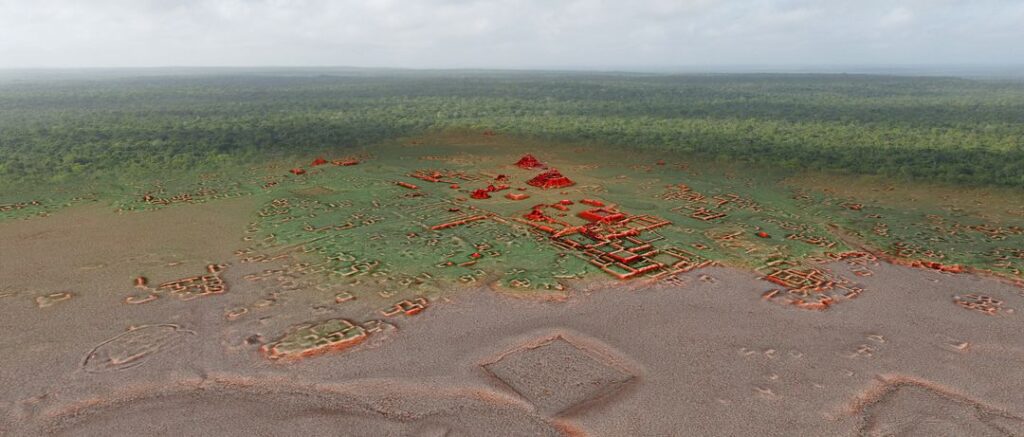

The Mayans were a civilisation known for their architecture, mathematics and astronomical beliefs, who date back as far as 2000BC. However, thanks to a discovery made at the El Mirador site in northern Guatemala, historians are able to know more about their theories over how human beings ended up on Earth. Archaeologist Richard Hansen took Morgan Freeman to see a spectacular discovery deep in the jungles during the filming of “The Story of God”.

He told Mr Freeman in 2017: “We like to think of Los Angeles and New York as being modern cities, but these guys had the same perspective of their own city.

“They had water delivery systems. they had freeways – the very first in the world.

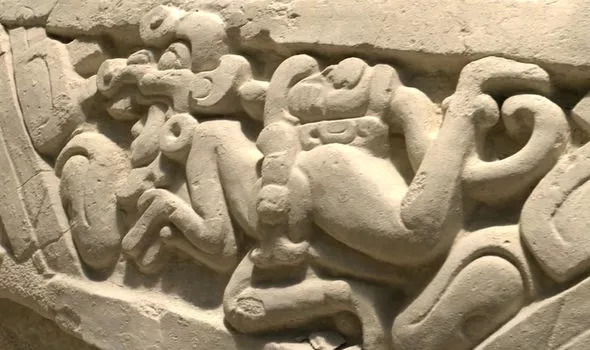

“This is one of the most interesting excavations we have ever had.

“This is art that was carved in stucco hundreds of years before Christ and it has an incredible scene showing the entire pantheon of the Mayan religion.

This is one of the most interesting excavations we have ever had

Richard Hansen

“This is the Mayan Bible, the Mayan Genesis story with all the deities that are needed to tell the story.”

Mr Hansen went on to reveal what he believed the stonework represented.

He added: “This is the oldest version of the Mayan’s sacred story of creation that has ever been found.

“The focus is on two swimmers carrying a severed head.

“It’s this head right here that gave us the clue who this might be a the first place.

“We think this is Hunahpu – one of the hero twins that serves the whole process of creation.”

The Mayan Hero Twins are the central figures of the oldest Mayan myth to have been preserved in its entirety. Hunahpu and Xbalanque are portrayed as complementary forces – life and death, sky and Earth or day and night. The pair need each other to balance out the other and balance out the two sides of a single entity. It comes after another discovery was revealed when the truth was over when the Mayans thought the world would end.

In 2012, there was a brief frenzy after it was claimed that December 21 would mark the end of the world because it was the end-date of a 5,126-year cycle on the Mayan calendar. However, thanks to the discovery of a stone slate in Tikal, Guatemala, archaeologists are able to understand more about this key date. Stanley Guenter, a world-leading decoder of Mayan inscriptions, revealed during the same series: “This is stela 10, you can see we’ve got a king – there is his head and big headdress full of feathers, [his] shoulders, all of his jewellery and down to his feet.

“If you look down below, we can actually see we have a captive and we can see his hands and even legs – all tied up for sacrifice.

“[On the back] we have a date that gives us a specific point in time – 11 years and 360 days, then we have three katuns – which are 20 years each.

“So that is another 60, and then we have nine b’ak’tuns, because this is a date of about 525AD.

“So if you remember we had 13 b’ak’tuns ended in 2012, but the really interesting thing is the monument does not stop there.”

Mr Guenter then went on to reveal how the entirety of the discovery reveals the 2012 prediction was just a single cycle inside a number of bigger cycles.

He continued: “It tells us there were 19 of the higher unit – the pictun – and even higher, 11 at the next unit.

“Each one of those units is 20 times larger than the previous, so what we see on this monument is that 13 b’ak’tuns was not the end of any calendar – just one cycle.

“It was just the start of a new cycle, a new beginning, that would go on for almost eternity.

“We have never found the end for the Mayans.”