99-million-year-old ticks sucked the blood of dinosaurs

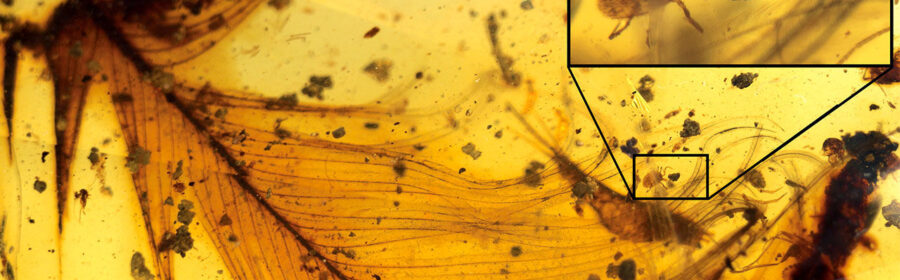

Researchers have uncovered some amazing pieces of the past preserved in ancient amber, from a new order of insects to whole baby birds. Now, another mind-blowing amber discovery surfaced, featuring a 99-million-year-old dinosaur feather along with several ticks, the oldest discovered so far.

One tick still clings to the dino feather, engorged from its last blood meal, notes John Pickerell at National Geographic.

Abandon any Jurassic Park fantasies now before you get too excited. The extraction of DNA from amber has never been effective, and the short lifetime of DNA will make it too damaged to use anyway, states the press release.

But the new find, chronicled in the journal Nature Communications, does tell us a lot about the history and evolution of blood-sucking ticks.

David Grimaldi, paper co-author and American Museum of Natural History entomologist, was examining a group of amber specimens from a private collection when he and his colleagues realized they were looking at a feather and ticks, reports Nicholas St. Fleur at The New York Times.

“Holy moly this is cool,” Grimaldi tells St. Fleur he thought at the time. “This is the first time we’ve been able to find ticks directly associated with the dinosaur feathers.”

The researchers found five ticks stuck in the amber. these include a nymph or immature tick, the engorged tick, and two covered with beetle hair.

As Gretchen Vogel at Science reports, the larvae of these beetles live in nests and feed off of discarded bits of skin and feathers. They are covered in protective hairs that slough off, sometimes creating mats of the hairs in nests.

These tiny hairs tend to stick to anything else that visits the nest. So the presence of the larvae hair suggests that the ticks were infesting a dinosaur nest, possibly a brood of theropod dinos—the deep ancestors of modern birds.

As Pickrell reports, this find indicates two important things. First, it gives strong evidence to suggest that dinosaurs raised their young in nests. Second, it suggests that dinosaurs of the Cretaceous age had to deal with parasites like ticks as well.

“Seeing a tick preserved in the same resin flow as a feather provides a concrete example of the ecological relationship, where most of the previous evidence has been speculative,” Ryan McKellar, curator of invertebrate palaeontology at the Royal Saskatchewan Museum in Canada, who is not involved in the study, tells Pickrell.

Ricardo Pérez-de la Fuente, the co-author of the study and researcher at the Oxford University Museum of Natural History, had long been pursuing the idea that ticks were dino parasites, Rebecca Hersher at NPR reports.

Pérez-de la Fuente has previously examined ancient ticks from other bits of amber covered in beetle hairs. But the combo of the tick and feather is the first hard evidence placing the two critters in close proximity.

Even so, most researchers believed that ticks only sucked the blood of early amphibians—and many millions of years later mammals—not feathered dinos, palaeontologist Ben Mans, who is not associated with the study, tells Hersher. This makes this most recent find a surprise.

One of those preserved ticks also represents a new species, which the researchers dubbed Deinocroton draculi. The scientists hope to follow up and figure out how the ancient tick fits into the family tree of the bloodsuckers.

As Pickrell reports, molecular clock analysis of modern ticks suggests that their ancient relatives first evolved some 200 to 300 million years ago, which means there’s still a long, bloody history of the critters for researchers to dig up.