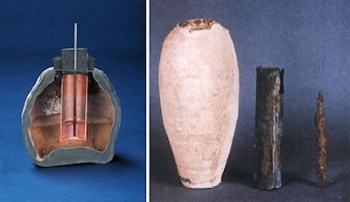

A battery around 200 BC found by the German Archaeologist in 1938.

It was in 1938, while working in Khujut Rabu, just outside Baghdad in modern-day Iraq, that German archaeologist Wilhelm Konig unearthed a five-inch-long (13 cm) clay jar containing a copper cylinder that encased an iron rod.

The vessel showed signs of corrosion, and early tests revealed that an acidic agent, such as vinegar or wine had been present.

They are commonly considered to have been intentionally designed to produce an electric charge.

“They are a one-off. As far as we know, nobody else has found anything like these. They are odd things; they are one of life’s enigmas.”

Form and Function:

Railway construction in Baghdad in 1936, uncovered a copper cylinder with a rod of iron amongst other finds from the Parthian period. In 1938, these were identified as primitive electric cells by Dr. Wilhelm Konig, then the director of the Baghdad museum laboratory, who related the discovery to other similar finds (Iraqi cylinders, rods and asphalt stoppers, all corroded as if by some acid, and a few slender Iron and Bronze rods found with them). He concluded that their purpose was for electroplating gold and Silver jewellery.

The Object he first found (left), was a 6-inch high pot of bright yellow clay containing a cylinder of sheet-copper 5 inches by 1.5 inches. The edge of the copper cylinder was soldered with a lead-tin alloy comparable to today’s solder. The bottom of the cylinder was capped with a crimped-in copper disc and sealed with bitumen or asphalt. Another insulating layer of Asphalt sealed the top and also held in place an iron rod suspended into the centre of the copper cylinder.

Two separate experiments with replicas of the cells have produced a 0.5-Volt current for as long as 18 days from each battery, using an electrolyte 5% solution of Vinegar, wine or copper-sulfate, sulphuric acid, and citric acid, all available at the time. (One replica produced 0.87-Volts).

From the BBC News Article

Most sources date the batteries to around 200 BC – in the Parthian era, circa 250 BC to AD 225. Skilled warriors, the Parthians were not noted for their scientific achievements.

“Although this collection of objects is usually dated as Parthian, the grounds for this are unclear,” says Dr St John Simpson, also from the department of the ancient Near East at the British Museum.

“The pot itself is Sassanian. This discrepancy presumably lies either in a misidentification of the age of the ceramic vessel, or the site at which they were found.”

From the same Article, these prophetic words of wisdom:

‘War can destroy more than people, an army or a leader. Culture, tradition, and history also lie in the firing line. Iraq has a rich national heritage. The Garden of Eden and the Tower of Babel are said to have been sited in this ancient land. In any war, there is a chance that priceless treasures will be lost forever, articles such as the “ancient battery” that resides defenseless in the museum of Baghdad’.

Unfortunately, the Baghdad batteries are now lost to us following the looting of the Baghdad museum in 2003.

This article appeared in the Guardian: Thursday, April 22 2004.

The situation in Iraq makes the fate of the 8,000 or so artefacts still missing from the National Museum of Baghdad ever more uncertain. Among them is an unassuming looking, 13cm long clay jar that represents one of archaeology’s greatest puzzles – the Baghdad battery. The enigmatic vessel was unearthed by the German archaeologist Wilhelm Koenig in the late 1930s, either in the National Museum or in a grave at Khujut Rabu, a Parthian site near Baghdad (accounts differ). The corroded earthenware jar contained a copper cylinder, which itself encased an iron rod, all sealed with asphalt. Koenig recognised it as a battery and identified several more specimens from fragments found in the region.

He theorised that several batteries would have been strung together, to increase their output, and used to electroplate precious objects. Koenig’s ideas were rejected by his peers and, with the onset of the second world war, subsequently forgotten.

Following the war, the fresh analysis revealed signs of corrosion by an acidic substance, perhaps vinegar or wine. An American engineer, Willard Gray, filled a replica jar with grape juice and was able to produce 1.5-2 volts of power. Then, in the late 1970s, a German team used a string of replica batteries successfully to electroplate a thin layer of silver.

About a dozen such jars were held in Baghdad’s National Museum. Although their exact age is uncertain, they’re thought to date from the Sassanian period, approximately AD 225-640. While it’s now largely accepted that the jars are indeed batteries, their purpose remains unknown. What were our ancestors doing with (admittedly, tiny) electric charges, 1,000 years before the first twitchings of our modern electrical age?

Certainly, the batteries would have been highly-valued objects: several were needed to provide even a small amount of power. The electroplating theory remains a strong contender, while a medical function has also been suggested – the Ancient Greeks, for example, are known to have used electric eels to numb pain.

Of particular interest in relation to the Baghdad Batteries is the suggestion that they were used in order to electroplate Copper Vases with silver, which were also once to be found in the Baghdad museum. They had been excavated from Sumerian sites in southern Iraq, dating 2,500 -2,000 BC.

Paul T. Keyser of the University of Alberta in Canada has come up with an alternative suggestion. Writing in the prestigious archaeological Journal of Near Eastern Studies, he claims that these batteries were used as an analgesic. He points out that there is evidence that electric eels were used to numb an area of pain or to anaesthetize it for medical treatment. The electric battery could have provided a less messy and more readily available method of analgesic.

Of course, the 1.5 volts that would have been generated by such a device would not do much to deaden a patch of skin, so the next conclusion was that these ancient people must have discovered how to link up several batteries in series to produce a higher voltage.

‘The Chinese had developed acupuncture by this time, and still use acupuncture combined with an electric current. This may explain the presence of needle-like objects found with some of the batteries’