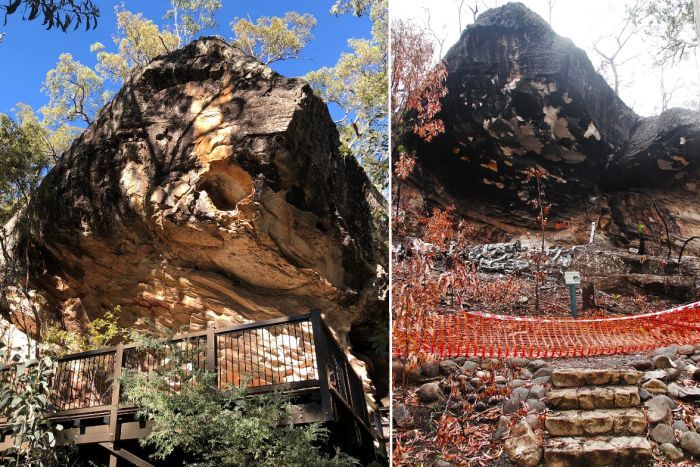

The aftermath of fire damage to important rock art at the Baloon Cave tourist destination, Carnarvon Gorge, Queensland, Australia

The ancient aboriginal rock art in the Baloon Cave in Australia can not be restored following the fire damage, caused by a recycled plastic walkway, ignited into a fireball in 2018.

After the recycled plastic walkway, old rock art including handprints and carving petroglyphs was destroyed, supposedly protecting the site, exploded into a ball of flames during a bushfire in Carnarvon National Park last year.

The artwork dating back several thousands of years has now been lost forever as experts who assessed the site announced that it cannot possibly be restored.

Some of the painted hand stencils date back 8,000 years while others had been created in more recent times, and Dale Harding, a member of the Baloon Cave working group, told ABC.net that the Aboriginal rock art was part of an ongoing cultural project providing links between his Bidjara, Ghungalu and Garingbal ancestors. Now, after realizing the extent of the destruction caused at Baloon Cave during 2018’s devastating Queensland bushfires, Mr. Harding has called for the removal of “all flammable structures” at vulnerable sites across the country.

Furthermore, the Brisbane Times spoke with Griffith University anthropologist and archaeologist, Paul Tacon, who described the fire as “a huge bomb going off” and that he was “horrified” to see the damage and destruction first-hand at the site.

Talking of what the loss means, culturally, to the indigenous Bidjara, Ghungalu and Garingbal communities, Mr. Harding said the art was the “foundation and the basis of who I identify as.” He added that his elders describe the whole Aboriginal rock art network as being “a university, a hospital and a cathedral” and that the incident was akin to the “destruction of Notre Dame Cathedral for the people of Paris, and that can’t be taken back,” he lamented.

Trying to understand how such a terrible thing could happen, Professor Tacon said the destruction would “not have occurred” if it hadn’t been for the installation of recycled plastic walkways, which he describes as “solidified petroleum.” Tacon said that if you have a hot fire underneath these plastics, they melt and then explode into a fireball, “and that’s exactly what happened.”

Detailing the damage, Professor Tacon said a chunk of rock from a set of “hafted stone axes” located high on the wall broke away and what’s left now has a large crack running through it. What’s more, the ancient cave art also suffered extensive water damage from the steam that was released from the plastic as it burned.

What is perhaps most worrying in this story is that a similar incident occurred in 2008 when a fire at Keep River in the Northern Territory set off another recycled-plastic walkway, and that fireball also caused numerous paintings and engravings within a natural stone archway to crack and crumble away.

Professor Tacon said “this stuff is really dangerous,” and he wants to see political steps taken to assure “no-one ever uses this [recycled-plastic] in a rock shelter with art again.” He suggested replacing them with “non-destructive platforms made out of steel, or concrete and steel.”

Responding to the cultural catastrophe Environment Minister Leeanne Enoch said that personally, she was absolutely devastated, being herself a Quandamooka woman from North Stradbroke Island. After visiting the damaged site, she said she had “felt every bit of the pain that everybody else felt and that there were a lot of tears shed that day,” and that experts had assessed the site confirming it could not be restored.

Since last year, Ms. Enoch’s Environment department has removed plastic boardwalks from other sites of cultural heritage around Queensland, but she outright rejected Professor Tacon’s suggesting that wooden boardwalks should also be removed.

However, this case of destruction at the Baloon Cave is only the beginning of the end for Australia’s ancient arts, most of which are set to vanish as a consequence of environmental pollution.

A Creative Spirits article explains that the “groove depth” measured on petroglyphs has decreased significantly over the last few decades because of a sharp increase in the number of cars in Australia.

Robert Bednarik, the founder of the Australian Rock Art Research Association, said small changes in carbon dioxide levels, temperature, and humidity, influence the growth of microorganisms and algae, which cause irreparable damage.

Even if an ancient engraving is not directly exposed to rain, Aboriginal rock engravings crumble by about half a grain of rock per year, through dew and fog settling in the grooves. While traditionally it was customary for indigenous specialists to repair and renew their ancestral artworks, National Parks today forbid Aboriginal people to do this. Thus, the only petroglyphs that you will see 100 years from now, according to Dr. Bednarik, are those very deeply carved, representing a small minority.

Talking of cultural issues in the land down under, it would seem Australian political culture has run ahead of itself and the relentless fight for control is having a catastrophic effect on the environment and on Aboriginal culture. Only yesterday a Daily Mail article reported that the Green’s political party leader, Richard Di Natale is regularly criticized by the Conservatives for opposing “hazard-reduction burns,” and Facebook critics have accused the Greens of being responsible for the current bushfires.

Now, the Australian environment minister is resisting getting rid of dangerous wooden walkways and cultural authorities won’t allow the repainting of rock art by indigenous craftspeople. Even though Dr. Bednarik says without this type of preservation most of them will be gone within a century. We do indeed live in a topsy-turvy world, in which carts so often lead horses, and politicians advise scientists.