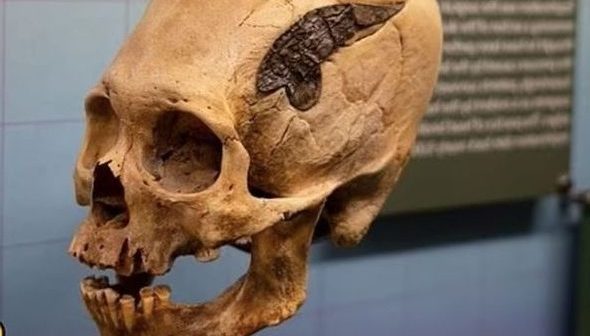

Archaeologists stunned as 2,000-year-old skull bound by metal evidence of ancient surgery

Archaeologists were taken aback when a 2,000-year-old skull was discovered bound by metal evidence of ancient surgery. The 2,000-year-old skull of a Peruvian warrior bound by metal, which is one of the earliest examples of ancient surgery, has astounded archaeologists.

The elongated skull, which has been fused together with metal, is currently on display at the SKELETONS: Museum of Osteology in Oklahoma, USA. The museum has described the find as one of its “most interesting” pieces.

The skull is thought to have belonged to a Peruvian warrior who was killed in a battle around 200 years ago. When the warrior returned from battle seriously injured, Peruvian surgeons are said to have performed a miraculous surgery on his skull.

The elongation of the museum’s structure was “achieved through head binding beginning at a very young age,” according to the museum’s Facebook page.

This was a practice used to demonstrate social status.

A piece of metal is thought to have been implanted by ancient Peruvian surgeons to repair the fractured skull. The material used was “not poured as molten metal,” according to the museum, and the plate was “used to help bind the broken bones.”

The alloy’s exact composition is unknown.

“The material used was not poured as molten metal,” the museum explained.

“We have no idea what the alloy’s composition is.”

The plate served as a binding agent for the broken bones.

“While we can’t say for sure whether anaesthesia was used, we do know that many natural remedies for surgical procedures existed during this time period.”

The procedure on the skull, according to experts, demonstrates that ancient peoples were capable of performing complex surgery and medical procedures.

“We don’t have a ton of background on this piece, but we do know he survived the procedure,” the museum wrote.

“You can see that it’s tightly fused together based on the broken bone surrounding the repair.

“The surgery went well.”

The skull had been in the museum’s private collection for quite some time. However, the artefact was later put on display in 2020, following a surge in the public interest.

“Traditionally, silver and gold were used for this type of procedure,” a SKELETONS: Museum of Osteology spokesperson told the Daily Star.

The Peruvian region where the skull was discovered is well-known for surgeons who devised a series of complicated procedures to treat a fractured skull.

At the time, the type of skull injury seen here was fairly common.

This is due to the use of projectiles in battle, such as slingshots.

In addition, elongated skulls were quite common.