A 2,000-Year-Old Antler In Vietnam May Be Oldest Music Instrument Of Its Kind

An unusual deer antler found in Vietnam may be one of the oldest string instruments ever unearthed in Southeast Asia.

Discovered at a site along the Mekong River, the 2,000-year-old instrument is like a single-stringed harp and may have been a great-grandparent to the complex musical instruments people still pluck today in Vietnam.

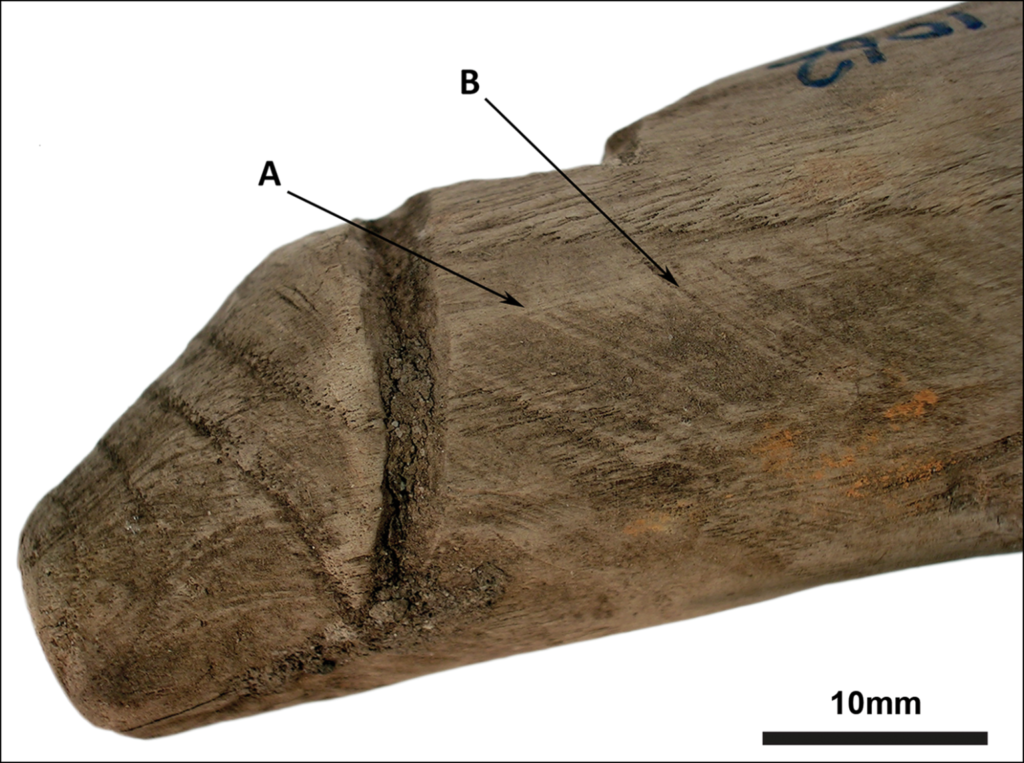

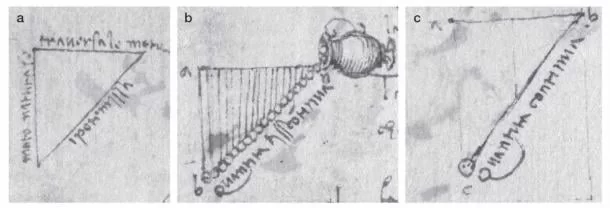

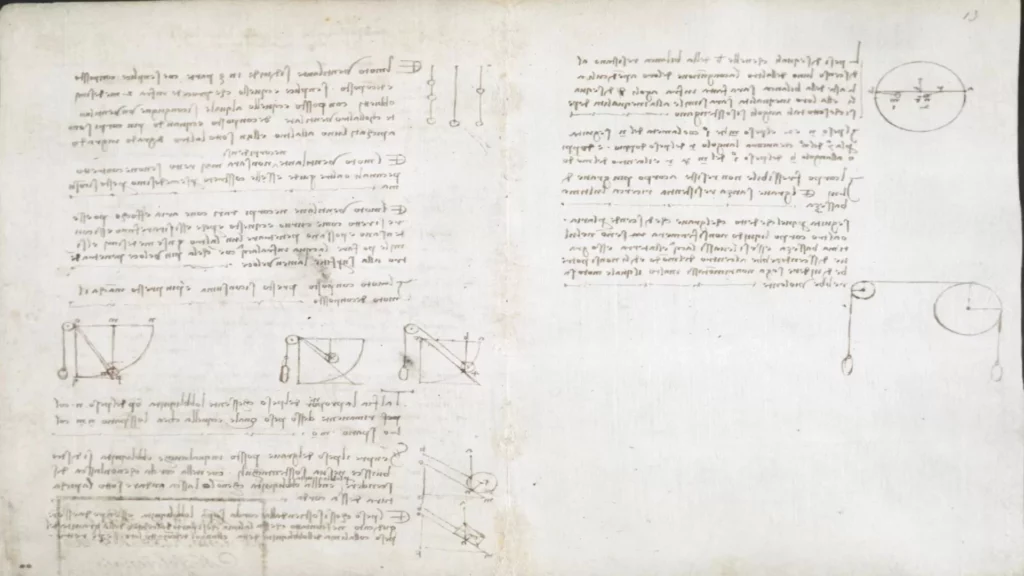

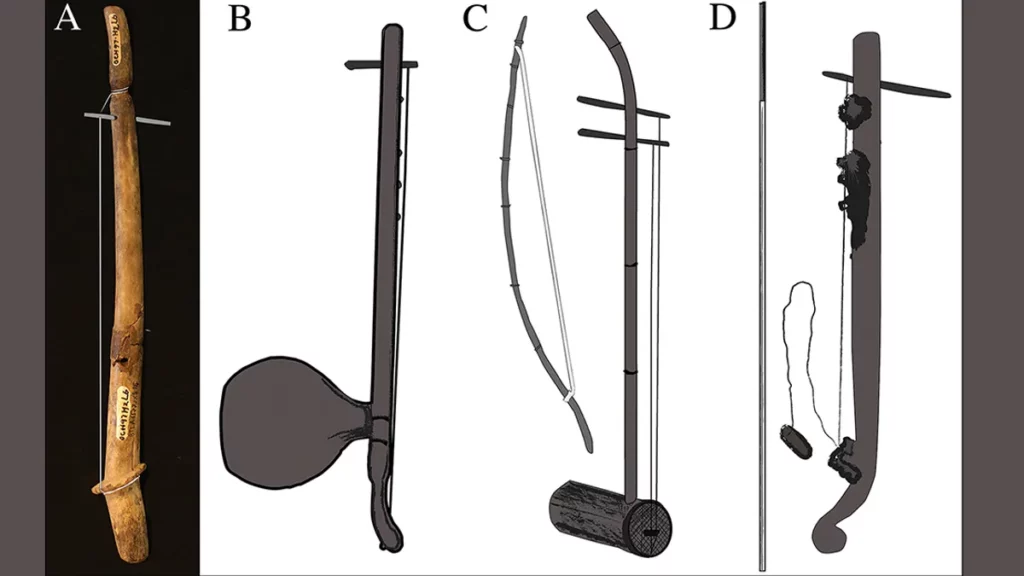

The artifact consists of a 35-centimeter-long piece of deer antler with a hole at one end for a peg, which was likely used to tune the string like the keys at the top of a guitar. While the string eroded away long ago, the object also features a bridge that was perhaps used to support the string.

Archaeologists from the Australian National University and Long An Museum in Vietnam recently described the fascinating objects in a new paper, reaching the conclusion that it was almost certainly a stringed instrument that was plucked to create music.

“No other explanation for its use makes sense,” Fredeliza Campos, lead researcher and PhD student from ANU, said in a statement seen by IFLScience.

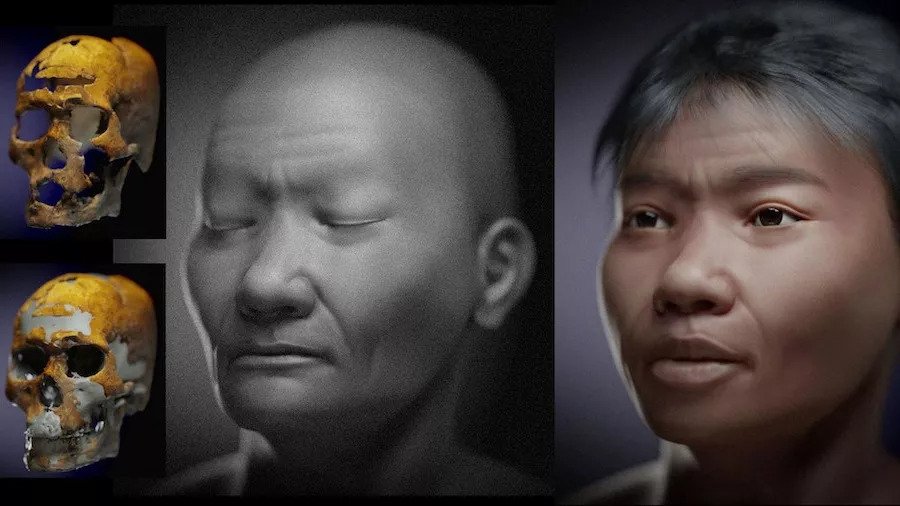

The antler most likely came from a Sambar deer or an Indian hog deer, two species that are native to mainland Southeast Asia.

The team dated the object to 2,000 years old from Vietnam’s pre-Óc Eo culture along the Mekong River, which is exceptionally early for this kind of instrument.

“This stringed instrument, or chordophone, is one of the earliest examples of this type of instrument in Southeast Asia. It fills the gap between the region’s earliest known musical instruments – lithophones or stone percussion plates – and more modern instruments,” she added.

There’s evidence to suggest that many ancient cultures had a rich and lovely music culture, but it often escapes the archaeological record. Songs don’t stick around in rocky sediments, after all.

For instance, ancient Greece is one of the most studied portions of ancient history and we know enjoying music played a key part in their culture, as shown by the number of artworks showing instruments being tooted and plucked. However, the quest to discover what the music sounded like has been described as a “maddening enigma.”

To better understand the music cultures of ancient Vietnam, the researchers sifted through a catalog of over 600 bone artifacts found in the area. Their analysis indicates that this fashioned antler fits the bill and shows the emergence of contemporary Vietnamese musical instruments, such as the K’ný.

“The K’ný is a single-string bowed instrument that is uniquely controlled by the player’s mouth, which also acts as a resonator. It can play a wide variety of sounds and tones, much more than a chromatic scale you often hear on a piano,” added Campos.

The new study was published in the journal Antiquity this week.