Israel Museum obtains world’s ‘first Jewish coin’

The Israel Museum has acquired over 1,200 ancient silver Persian coins, among the earliest known currency from the area, including what the museum has identified as the world’s oldest Jewish coin.

The coins, dated to the 5th and 4th centuries BCE when the region was controlled by the Persian Empire, constitute “the largest collection in the world of Persian-period coins.”

The collection includes a number of previously unknown varieties, the museum said. Chief among the rare artefacts is a silver drachm, an ancient coin based upon the Greek drachma, which, in clearly legible Aramaic script, bears the word yehud, or Judea.

“It’s the earliest coin from the province of Judea,” the museum’s chief curator of archaeology, Haim Gitler, said in an interview with The Times of Israel, calling the 5th-century silver drachm the “first Jewish coin.”

The coin collection dates to the period a century or more after the Achaemenid Persian Empire under Cyrus II (the Great) conquered and annexed the Neo-Babylonian Empire in 539 BCE. The Persians ruled the Levant for the next two centuries until Alexander of Macedon stormed through and toppled their empire. Roughly a century before Persia conquered the Middle East, the earliest known currency was minted from electrum — a silver-gold alloy — in Lydia, western Asia Minor.

The idea of precious metal coinage spread across the empire. Judea, Samaria and Philistia, part of the satrapy of Syria and Jerusalem, began minting their own coins shortly thereafter. The 3.58 gram yehud coin — a hair or two lighter than today’s one shekel coin — was reportedly found in the hills southwest of Hebron and was bought at auction by New York antiquities collector Jonathan Rosen.

Rosen, “one of the world’s most important private collectors of Mesopotamian art” according to The New York Times, agreed to donate his entire collection of Persian-era coins to the museum in March 2013. The acquisition was completed in November. Apollo, an international art magazine, ranked the collection among the top museum acquisitions of 2013.

Although there are a handful of other examples of coins bearing the name Judea, Gitler said the silver drachm was a “unique coin” in its design, and was likely minted in Philistia, the coastal plain encompassing the modern cities of Ashdod, Ashkelon and Gaza, for use in the province of Jerusalem. “Only later did Judea start to mint its own coins,” he said.

Then, as now, Judea, Samaria and Philistia sat at the crossroads of civilizations and at the far reaches of the Persian Empire, and local artisans would imitate styles from coins that arrived from abroad.

The coinage represented in the collection consequently exhibits a stunning array of artistic influences from Persia, Greece, Anatolia and Egypt. Many coins feature owls, a symbol closely associated with the goddess Athena, both of which appeared on Greek drachmas in antiquity. Other coins bear images of deities, heroes, mythical beasts and animals familiar to the Middle East — including camels, horses, cows, eagles, and lions.

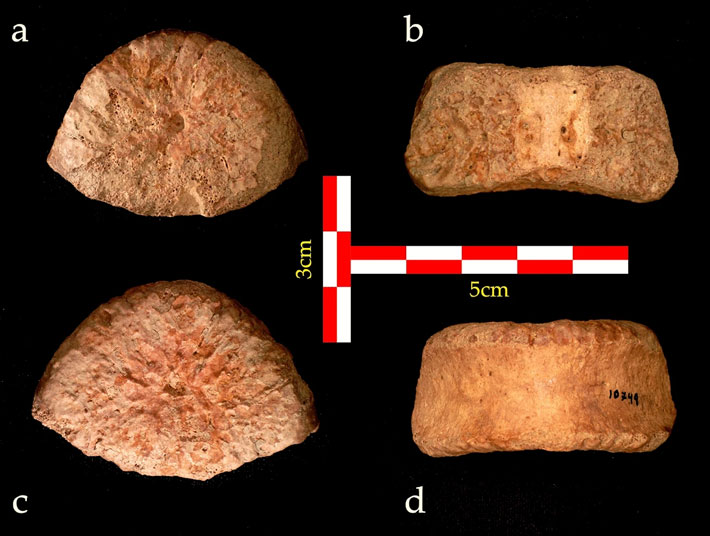

The Judean drachm’s iconography is representative of the local fusion of artistic designs. Emblazoned on its obverse is a gorgoneion, a Greek icon of the head of a gorgon that serves as a talisman against evil, but its hair is stylized like the Egyptian goddess Hathor. On the reverse side is a lion astride a cow with the Aramaic letters yod, heh and dalet. The exact meaning of the coin’s iconography remains undetermined.

Based on the stylization of the gorgon head, which in earlier incarnations was demonic and bestial and over the centuries became more anthropomorphic, and the style of the Aramaic script, Gitler dated the coin to the early 4th century BCE.

“We barely have any information or texts describing the Persian period in Palestine, so almost all that we know comes from these coins,” he said. Gitler explained that the tiny images engraved in silver offer a glimpse into the appearance, manner of dress and language spoken by inhabitants of the region at the time.

It is clear from the collection that the die-engravers of Persian Palestine who designed the coins demonstrated a proclivity for creative expression unseen elsewhere in the empire, creating a “local flavour” of coinage, Gitler said. Coins from Tyre and Sidon, just up the coast, have a much smaller variety of styles.

A Philistian drachm from the late 5th century BCE in the collection employs a clever example of “optical trickery” in its design, he noted.

When turned 90˚ counterclockwise, the lion on the coin’s reverse becomes the helmet of the bearded man, and its paws become the man’s hair. Gitler said such illusions were fairly common, noting that a Samarian coin from the same period showed the head of a bearded man whose face is composed of two faces in profile. Hidden owls also roost within the designs of other creatures.

“The coins really show us a variety of motifs which is unequaled” in the Persian Empire, Gitler said. “It shows that the people who were designing these coins weren’t just making the coins because they had to do them, but they enjoyed doing it.”

A selection of coins from the collection is now on display in the Israel Museum’s Archaeology Wing, including the lion optical illusion coin shown above.

“Of course in the future we’ll start incorporating more of the collection,” he said, voicing interest in holding an exhibition of a selection of the coins in the collection which he said would be “even more amazing” than the White Gold exhibit in 2012 that showcased the world’s earliest electrum currency.