First Australians ate giant eggs of huge flightless birds, ancient proteins confirm

Proteins extracted from fragments of prehistoric eggshells found in the Australian sands confirm that the continent’s earliest humans consumed the eggs of a two-metre tall bird that disappeared into extinction over 47,000 years ago.

Burn marks discovered on scraps of ancient shell several years ago suggested the first Australians cooked and ate large eggs from a long-extinct bird – leading to fierce debate over the species that laid them.

Now, an international team led by scientists from the universities of Cambridge and Turin have placed the animal on the evolutionary tree by comparing the protein sequences from powdered egg fossils to those encoded in the genomes of living avian species.

“Time, temperature and the chemistry of a fossil all dictate how much information we can glean,” said senior co-author Prof Matthew Collins from the University of Cambridge’s Department of Archaeology.

“Eggshells are made of mineral crystals that can tightly trap some proteins, preserving this biological data in the harshest of environments – potentially for millions of years”

Prof Matthew Collins

According to findings published in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, the ancient eggs came from Genyornis: a huge flightless “mihirung” – or ‘Thunder Bird’ – with tiny wings and massive legs that roamed prehistoric Australia, possibly in flocks.

Fossil records show that Genyornis stood over two metres tall, weighed between 220-240 kilograms, and laid melon-sized eggs of around 1.5 kg. It was among the Australian “mega-fauna” to vanish a few thousand years after humans arrived, suggesting people played a role in its extinction.

The earliest “robust” date for the arrival of humans to Australia is some 65,000 years ago.

Burnt eggshells from the previously unconfirmed species all date to around 50 to 55 thousand years ago – not long before Genyornis is thought to have gone extinct – by which time humans had spread across most of the continent.

“There is no evidence of Genyornis butchery in the archaeological record. However, eggshell fragments with unique burn patterns consistent with human activity have been found at different places across the continent,” said senior co-author Prof Gifford Miller from the University of Colorado.

“This implies that the first humans did not necessarily hunt these enormous birds, but did routinely raid nests and steal their giant eggs for food,” he said. “Overexploitation of the eggs by humans may well have contributed to Genyornis extinction.”

While Genyornis was always a contender for the mystery egg-layer, some scientists argued that – due to shell shape and thickness – a more likely candidate was the Progura or ‘giant malleefowl’: another extinct bird, much smaller, weighing around 5-7 kg and akin to a large turkey.

The initial ambition was to put the debate to bed by pulling ancient DNA from pieces of shell, but genetic material had not sufficiently survived the hot Australian climate.

Miller turned to researchers at Cambridge and Turin to explore a relatively new technique for extracting a different type of “biomolecule”: protein.

While not as rich in hereditary data, the scientists were able to compare the sequences in ancient proteins to those of living species using a vast new database of biological material: the Bird 10,000 Genomes (B10K) project.

“The Progura was related to today’s megapodes, a group of birds in the galliform lineage, which also contains ground-feeders such as chickens and turkeys,” said study first author Prof Beatrice Demarchi from the University of Turin.

“We found that the bird responsible for the mystery eggs emerged prior to the galliform lineage, enabling us to rule out the Progura hypothesis. This supports the implication that the eggs eaten by early Australians were laid by Genyornis.”

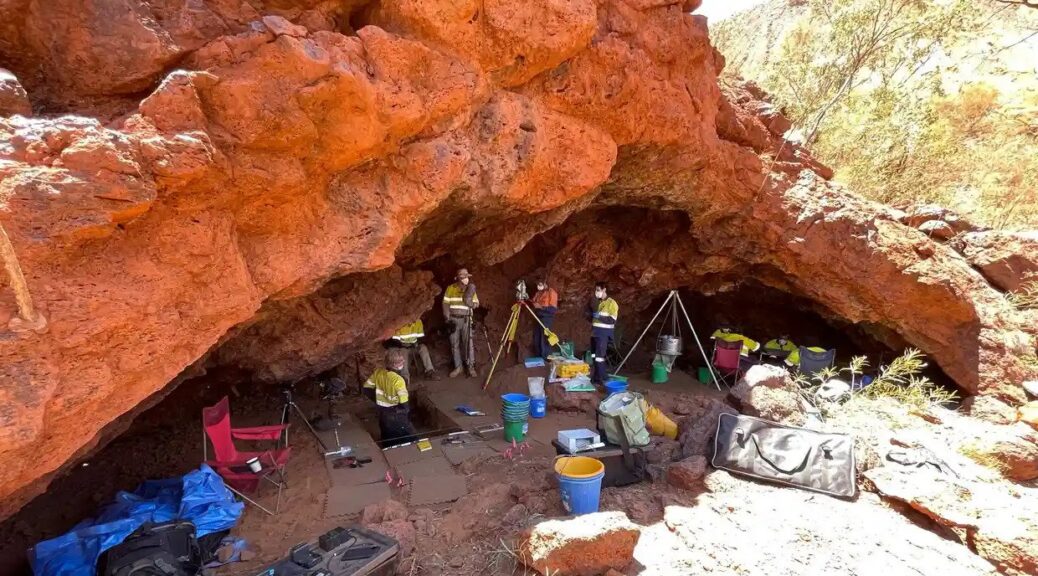

The 50,000-year-old eggshell tested for the study came from the archaeological site of Wood Point in South Australia, but Prof Miller has previously shown that similar burnt shells can be found at hundreds of sites on the far western Ningaloo coast.

The researchers point out that the Genyornis egg exploitation behaviour of the first Australians likely mirrors that of early humans with ostrich eggs, the shells of which have been unearthed at archaeological sites across Africa dating back at least 100,000 years.

Prof Collins added: “While ostriches and humans have co-existed throughout prehistory, the levels of exploitation of Genyornis eggs by early Australians may have ultimately proved more than the reproductive strategies of these extraordinary birds could bear.”