Blue Fibers Found in Dental Calculus of Maya Sacrifice Victims

More than 15 years after its discovery, Belize’s Midnight Terror Cave is still leaving clues about more than 100 people who were sacrificed to the Maya rain god there more than a millennium ago.

Used for burial during the Maya Classic period (A.D. 250 to 925), the cave was named by locals who were called to rescue an injured looter in 2006. A three-year excavation project by California State University, Los Angeles (Cal State LA) professors and students concluded that the more than 10,000 bones uncovered in the cave represented at least 118 people, many of whom had evidence of trauma inflicted on them around the time of death.

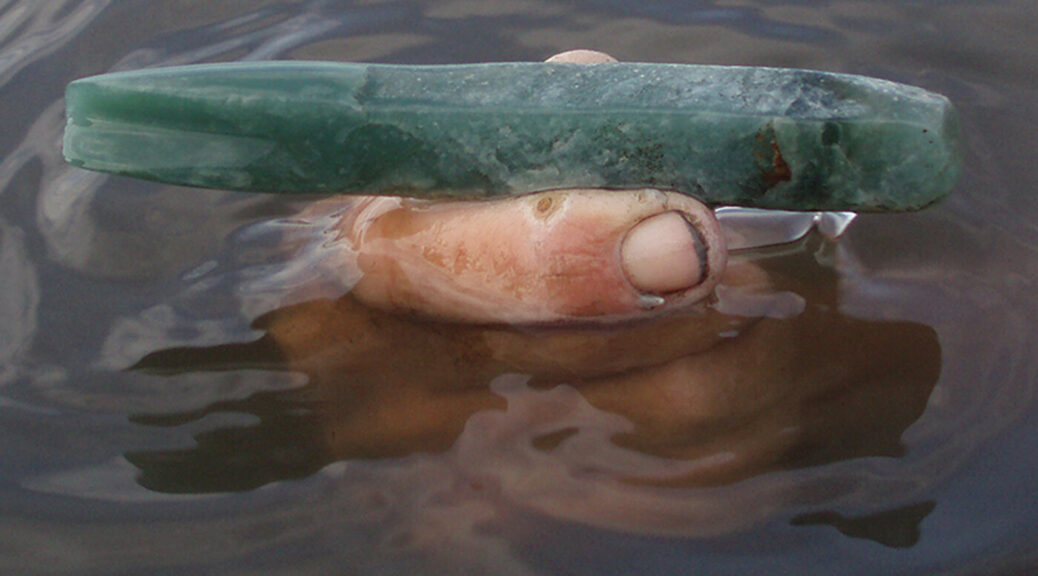

To dive deeper into the victims’ final moments, the latest research didn’t look at bones but instead at their mouths, investigating the calcified plaque from their teeth, known as dental calculus. The study, published Sept. 20 in the International Journal of Osteoarchaeology(opens in new tab), describes curious blue fibres clinging to the teeth of at least two of the victims.

Study lead author Amy Chan, who’s now an archaeologist working in cultural resource management, started her analysis of the Midnight Terror Cave teeth as a graduate student at Cal State LA, where she was interested in learning more about the dental health of the victims, she told Live Science by email.

“After finding minimal instances of dental pathology, I became interested in determining what foodstuffs the victims were consuming,” she said.

Dental calculus can preserve microscopic pieces of food that someone ate — such as pollen grains, starches and phytoliths, which are mineralized parts of plants — so Chan scraped the gunk off six teeth and sent it to study co-author Linda Scott Cummings(opens in new tab), president and CEO of the PaleoResearch Institute in Golden, Colorado. Scott Cummings found that the samples contained primarily cotton fibres and that several of those were dyed bright blue.

“The discovery of blue cotton fibres in both samples was a surprise,” Chan said, because “blue is important in Maya ritual.”

A unique “Maya blue” pigment has been found at other sites in Mesoamerica, where it seems to have been used in ceremonies — particularly to paint the bodies of sacrificial victims, Chan and colleagues wrote in their research paper. These blue fibres were also found in an agave-based alcoholic beverage at burials at Teotihuacan, an archaeological site in what is now Mexico.

But Chan and her team offered another explanation for the fibres found on the teeth: Perhaps the victims had cotton cloths in their mouths, possibly from the use of gags leading up to their sacrifice. If victims were in custody for extended periods of time, their dental calculus could have incorporated the blue fibres.

“It is interesting that they found coloured fibre in dental calculus,” Gabriel Wrobel(opens in new tab), a bioarchaeologist at Michigan State University who was not involved in the study, told Live Science by email. “Many researchers think that calculus only reflects diet, but this study is a great example of how much more information can be learned.”

Claire Ebert(opens in new tab), an environmental archaeologist at the University of Pittsburgh who was not involved in the study, told Live Science by email that she is “sceptical” that the blue fibres came from gags. However, she noted that dental calculus studies are important because they “can be used to look at other aspects of Maya life, ranging from ritual to domestic.”

An expanded study including both elite and non-elite people would be worthwhile “to see if the pattern can also be detected” or if “other explanations for the presence of fibers may be more logical,” Ebert said.

Chan and her team agree that their study, while providing the first evidence of blue fibers in the dental calculus of Maya individuals, has some limitations. First, the rate at which plaque forms and hardens varies based on the type of food eaten and a person’s physiology, so the researchers cannot know for certain when the fibers were trapped. Additionally, very few teeth of Midnight Terror Cave victims had dental calculus, to begin with, limiting the team’s analysis.

“Future studies will provide a more ample context for interpreting this data,” the researchers wrote in their study.