The MINI terracotta army: Hundreds of small warrior statues found in 2100-year-old pit in China

Inside a 2,100-year-old pit in China, archaeologists have discovered a miniature army of sorts: carefully arranged chariots and mini statues of cavalry, watchtowers, infantry and musicians.

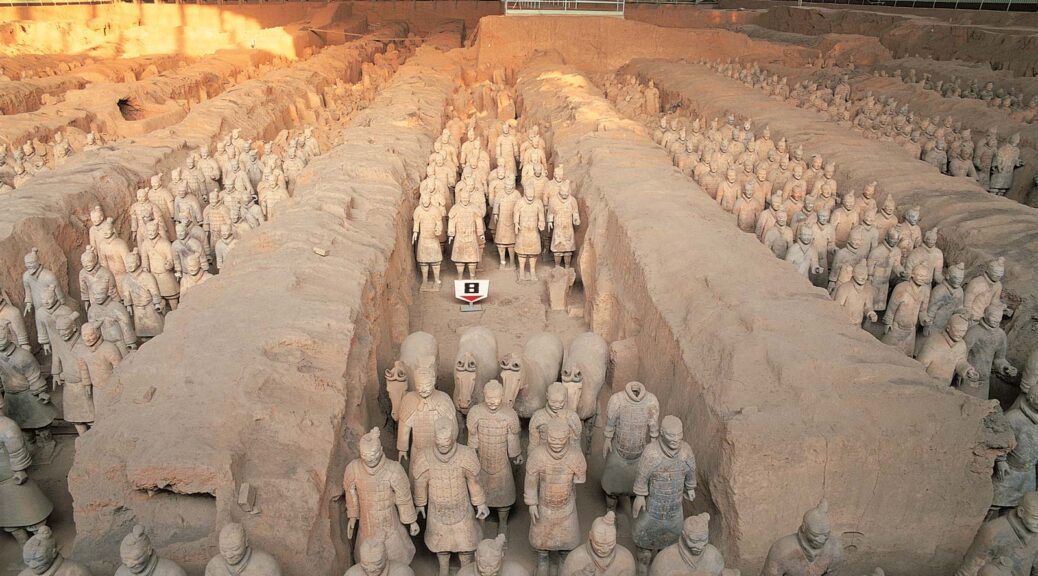

They look like a miniaturized version of the Terracotta Army — a collection of chariots and life-size sculptures of soldiers, horses, entertainers and civil officials — that was constructed for Qin Shi Huang, the first emperor of China.

Based on the design of the newfound artefacts, archaeologists believe that the pit was created about 2,100 years ago, or about a century after the construction of the Terracotta Army.

The southern part of the pit is filled with formations of cavalry and chariots, along with models of watchtowers that stand 55 inches (140 centimetres) high. At the pit’s centre, about 300 infantrymen stand alert in a square formation, while the northern part of the pit has a model of a theatrical pavilion holding small sculptures of musicians.

“The form and scale of the pit suggest that it accompanies a large burial site,” wrote archaeologists in a paper published recently in the journal Chinese Cultural Relics.

The “vehicles, cavalry and infantry in square formation were reserved for burials of the monarchs or meritorious officials or princes,” the archaeologists wrote.

The soldiers and cavalry in the newly discovered army are much smaller than those in the Terracotta Army. Based on the date, size and location of the pit, archaeologists believe that this newly discovered army may have been built for Liu Hong, a prince of Qi (a part of China), who was the son of Emperor Wu (reign 141–87 B.C.).

Hong was based in Linzi, a Chinese city near the newly discovered pit; he died in 110 B.C. “Textual sources record that Liu Hong was installed as the prince of Qi when he was quite young, and he, unfortunately, died early, without an heir,” archaeologists wrote in the journal article. Shortly before Hong’s death, according to writings by ancient historian Ban Gu, a comet appeared in the sky over China.

Where is the tomb?

If the pit and its ceramic army were meant to protect Liu Hong, or another senior royal family member, in the afterlife, then a tomb should be located nearby, the archaeologists wrote.

“There are possibly architectural remains or a path leading from the pit, but there is no way to explore the main burial chamber,” the researchers wrote, noting that the tomb itself may have been destroyed.

Older residents in the area have reported descriptions of a prominent earthen mound, some 13 feet (4 meters) high, near the pit, the study authors wrote. “Sometime in the 1960s or 1970s, workers removed the earth and flattened the area in order to widen the Jiaonan-Jinan Railway.”

The reports are corroborated by an aerial photograph taken in 1938 by the Japanese Air Force (at that time, Japan was at war with China). This picture shows a possible burial mound near the railway, the archaeologists noted.

From life size to mini-warriors

The Terracotta Army pits found beside the tomb of the first emperor of China are the only known examples of an army of life-size ceramic soldiers in China.

Shortly after the first emperor’s 210 B.C. death, his dynasty, known as the Qin dynasty, collapsed and a new dynasty, known as the Han, took over China.

Some of the Han dynasty rulers continued to build pits with armies of ceramic soldiers for their burials, but the soldiers were considerably smaller. For instance, the infantry sculptures in the newly discovered pit are between 9 and 12 inches (22 and 31 cm) tall, nowhere near the heights of the life-size soldiers buried near the tomb of the first emperor.

The pit, along with several other archaeological sites, was discovered in the winter of 2007 during construction work. After its discovery, the pit was excavated by the Cultural Relics Agency of Linzi District of Zibo city.

After excavation was complete, archaeologists from this agency analyzed the artefacts, working with researchers from the Shandong Provincial Institute of Cultural Relics and Archaeology.

A report on the pit was first published, in Chinese, in 2016, in the journal Wenwu. This report was recently translated into English and published in the journal Chinese Cultural Relics.