2,000-Year-Old Chinese Mummy still has Blood in her Veins, Making Her one of the World’s Best-Preserved Mummies

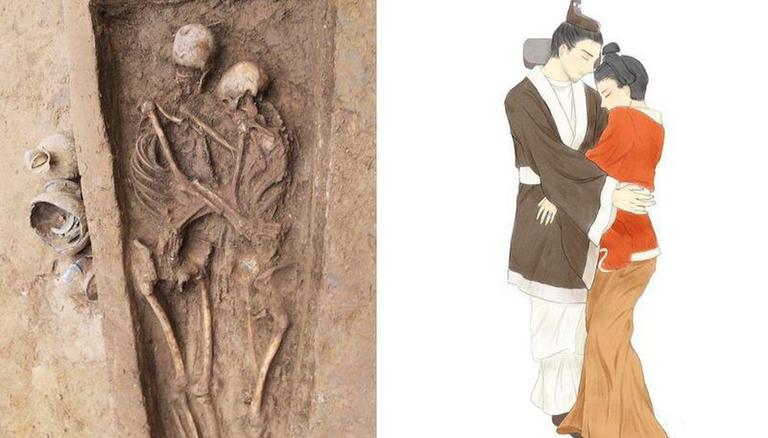

Xin Zhui died in 163 BC. When they found her in 1971, her hair was intact, her skin was soft to the touch, and her veins still housed type-A blood. Now more than 2,000 years old, Xin Zhui, also known as Lady Dai, is a mummified woman of China’s Han dynasty (206 BC-220 AD) who still has her own hair, is soft to the touch, and has ligaments that still bend, much like a living person.

She is widely recognized as the best-preserved human mummy in history.

Xin Zhui was discovered in 1971 when workers digging near an air raid shelter near Changsha practically stumbled across her massive tomb. Her funnel-like crypt contained more than 1,000 precious artefacts, including makeup, toiletries, hundreds of pieces of lacquerware, and 162 carved wooden figures which represented her staff of servants. A meal was even laid out to be enjoyed by Xin Zhui in the afterlife.

But while the intricate structure was impressive, maintaining its integrity after nearly 2,000 years from the time it was built, Xin Zhui’s physical condition was what really astonished researchers.

When she was unearthed, she was revealed to have maintained the skin of a living person, still soft to the touch with moisture and elasticity. Her original hair was found to be in place, including that on her head and inside of her nostrils, as well as the eyebrows and lashes.

Scientists were able to conduct an autopsy, during which they discovered that her 2,000-year-old body — she died in 163 BC — was in a similar condition to that of a person who had just recently passed.

However, Xin Zhui’s preserved corpse immediately became compromised once the oxygen in the air touched her body, which caused her to begin deteriorating. Thus, the images of Xin Zhui that we have today don’t do the initial discovery justice.

Furthermore, researchers found that all of her organs were intact and that her veins still housed type-A blood. These veins also showed clots, revealing her official cause of death: heart attack.

An array of additional ailments was also found throughout Xin Zhui’s body, including gallstones, high cholesterol, high blood pressure, and liver disease.

While examining Lady Dai, pathologists even found 138 undigested melon seeds in her stomach and intestines. As such seeds typically take one hour to digest, it was safe to assume that the melon was her last meal, eaten minutes before the heart attack that killed her.

So how was this mummy so well-preserved?

Researchers credit the airtight and elaborate tomb in which Lady Dai was buried. Resting nearly 40 feet underground, Xin Zhui was placed inside the smallest of four pine box coffins, each resting within the one larger (think of Matryoshka, only once you reach the smallest doll you’re met with the dead body of an ancient Chinese mummy).

She was wrapped in twenty layers of silk fabric, and her body was found in 21 gallons of an “unknown liquid” that was tested to be slightly acidic and containing traces of magnesium.

A thick layer of paste-like soil lined the floor, and the entire thing was packed with moisture-absorbing charcoal and sealed with clay, keeping both oxygen and decay-causing bacteria out of her eternal chamber. The top was then sealed with an additional three feet of clay, preventing water from penetrating the structure.

While we know all of this about Xin Zhui’s burial and death, we know comparatively little about her life.

READ ALSO: WELL PRESERVED 700-YEAR-OLD MUMMY FOUND BY CHANCE BY CHINESE ROAD WORKERS

Lady Dai was the wife of a high-ranking Han official Li Cang (the Marquis of Dai), and she died at the young age of 50, as a result of her penchant for excess. The cardiac arrest that killed her was believed to have been brought on by a lifetime of obesity, lack of exercise, and an opulent and over-indulgent diet.

Nevertheless, her body remains perhaps the best-preserved corpse in history. Xin Zhui is now housed in the Hunan Provincial Museum and is the main candidate for their research in corpse preservation.