The surprising truth about the construction of the Great Pyramids

“It’s not my day job,” Michel Barsoum begins as he recounts his foray into the mysteries of Egypt’s Great Pyramids.

As a well – respected ceramic researcher, Barsoum never expected his career to take him down a path of history, archeology, and “political” science with mixed – in materials research.

As a distinguished professor in the Department of Materials Science and Engineering at Drexel University, his daily routine consists mainly of teaching students about ceramics, or performing research on a new class of materials, the so-called MAX Phases, that he and his colleagues discovered in the 1990s.

These modern ceramics are machinable, thermal-shock resistant, and are better conductors of heat and electricity than many metals — making them potential candidates for use in nuclear power plants, the automotive industry, jet engines, and a range of other high-demand systems.

Then Barsoum received an unexpected phone call from Michael Carrell, a friend of a retired colleague of Barsoum, who called to chat with the Egyptian-born Barsoum about how much he knew of the mysteries surrounding the building of the Great Pyramids of Giza, the only remaining of the 7 wonders of the ancient world.

The widely accepted theory — that the pyramids were made of carved – out giant calcareous blocks that workers carried up ramps — was not only not embraced by everyone, but as important had quite a number of holes.

Burst out laughing

According to the caller, the mysteries had actually been solved by Joseph Davidovits, Director of the Geopolymer Institute in St. Quentin, France, more than 2 decades ago.

Davidovits claimed that the stones of the pyramids were actually made of a very early form of concrete created using a mixture of limestone, clay, lime, and water.

“It was at this point in the conversation that I burst out laughing,” Barsoum said. If the pyramids were indeed cast, he said, someone should have proven it beyond a doubt by now, in this day and age, with just a few hours of electron microscopy.

It turned out that nobody had completely proven the theory … yet.”What started as a 2-hour project turned into a 5-year odyssey that I undertook with one of my graduate students, Adrish Ganguly, and a colleague in France, Gilles Hug,” Barsoum said.

A year and a half later, after extensive scanning electron microscope observations and another testing, Barsoum and his research group finally began to draw some conclusions about the pyramids.

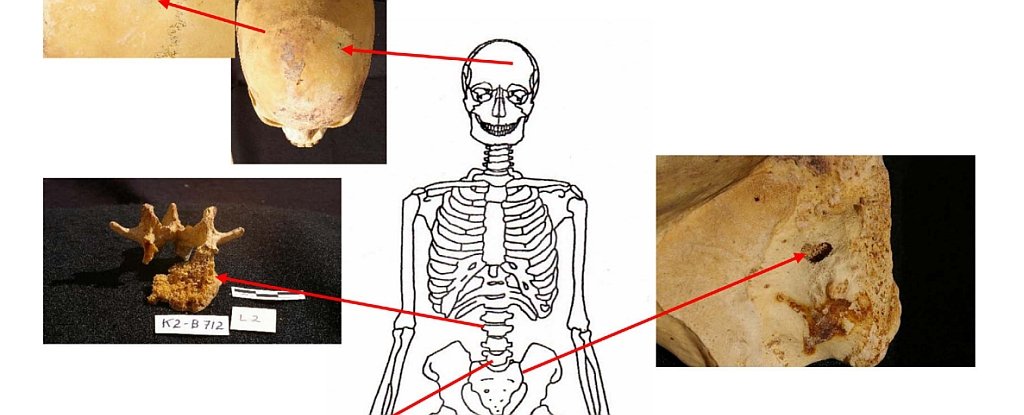

They found that the tiniest structures within the inner and outer casing stones were indeed consistent with a reconstituted limestone. The cement binding the limestone aggregate was either silicon dioxide (the building block of quartz) or a calcium and magnesium-rich silicate mineral.

The stones also had a high water content — unusual for the normally dry, natural limestone found on the Giza plateau — and the cementing phases, in both the inner and outer casing stones, were amorphous, in other words, their atoms were not arranged in a regular and periodic array. Sedimentary rocks such as limestone are seldom, if ever, amorphous.

The sample chemistries the researchers found do not exist anywhere in nature.

“Therefore,” Barsoum said, “it’s very improbable that the outer and inner casing stones that we examined were chiseled from a natural limestone block.”More startlingly, Barsoum and another of his graduate students, Aaron Sakulich, recently discovered the presence of silicon dioxide nanoscale spheres (with diameters only billionths of a meter across) in one of the samples. This discovery further confirms that these blocks are not natural limestone.

Generations misled

At the end of their most recent paper reporting these findings, the researchers reflect that it is “ironic, sublime and truly humbling” that this 4,500-year-old limestone is so true to the original that it has misled generations of Egyptologists and geologists and, “because the ancient Egyptians were the original — albeit unknowing — nanotechnologists.”As if the scientific evidence isn’t enough, Barsoum has pointed out a number of common sense reasons why the pyramids were not likely constructed entirely of chiseled limestone blocks.

Egyptologists are consistently confronted by unanswered questions: How is it possible that some of the blocks are so perfectly matched that not even a human hair can be inserted between them? Why, despite the existence of millions of tons of stone, carved presumably with copper chisels, has not one copper chisel ever been found on the Giza Plateau?

Although Barsoum’s research has not answered all of these questions, his work provides insight into some of the key questions. For example, it is now more likely than not that the tops of the pyramids are cast, as it would have been increasingly difficult to drag the stones to the summit.

Also, casting would explain why some of the stones fit so closely together. Still, as with all great mysteries, not every aspect of the pyramids can be explained. How the Egyptians hoisted 70-ton granite slabs halfway up the great pyramid remains as mysterious as ever.

Why do the results of Barsoum’s research matter most today? Two words: earth cement.”How energy intensive and/or complicated can a 4,500-year-old technology really be? The answer to both questions is not very,” Barsoum explains.

“The basic raw materials used for this early form of concrete — limestone, lime, and diatomaceous earth — can be found virtually anywhere in the world,” he adds.

“Replicating this method of construction would be cost-effective, long-lasting, and much more environmentally friendly than the current building material of choice: Portland cement that alone pumps roughly 6 billion tons of CO2 annually into the atmosphere when it’s manufactured.

“Ironically,” Barsoum said, “this study of 4,500-year-old rocks is not about the past, but about the future.”