Mystery behind Cleopatra’s tomb: Two mummies discovered in Egypt could help solve it

The mummies of two high-status ancient Egyptians discovered in a temple on the Nile delta may bring researchers a step closer to finding the remains of Cleopatra, the legendary Egyptian queen.

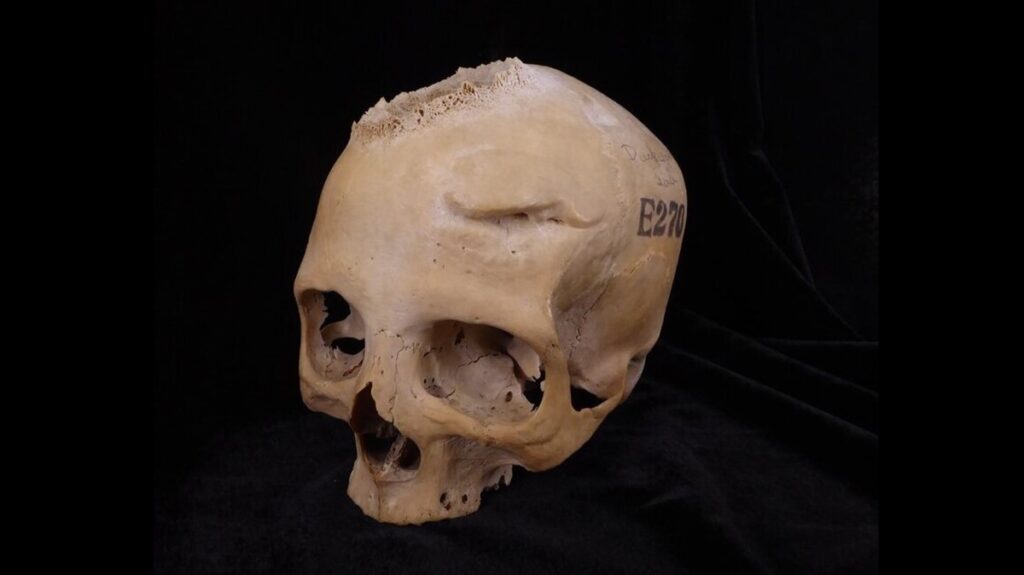

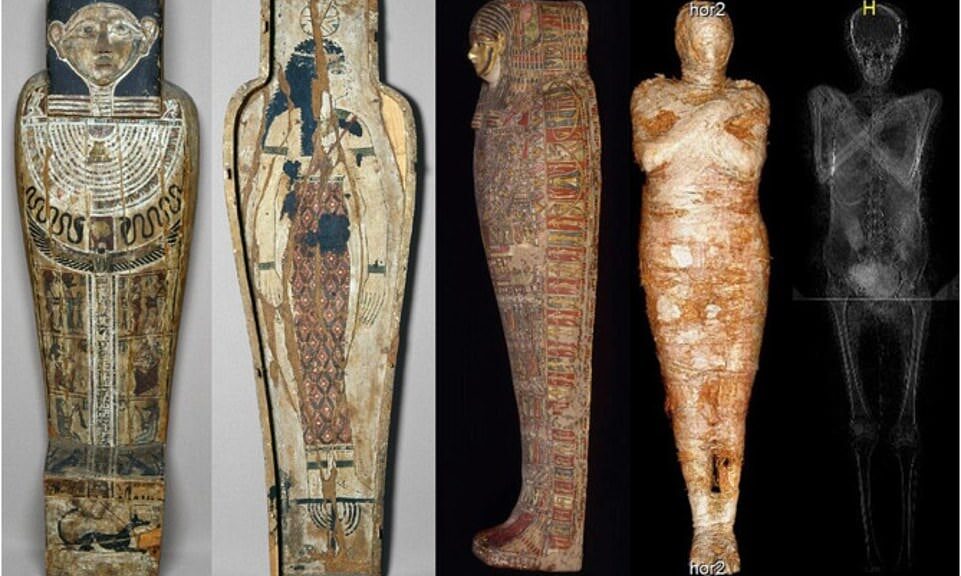

The mummies, which had lain undisturbed for 2,000 years, are in a poor state of preservation because water had seeped into the tomb, according to the Guardian.

But they were originally covered with gold leaf – a luxury reserved for only the top members of society’s elite – meaning they may have personally interacted with Cleopatra.

The male and female mummies may have been priests who played a key role in maintaining the power of the legendary Egyptian queen and her lover, Mark Anthony.

Also found at the site were 200 coins bearing Cleopatra’s name and her face, which would have been pressed based on Cleopatra’s direct instructions. The location of the long-lost tomb of Mark Antony and Cleopatra VII from the year 30 BC remains unknown, although it’s somewhere near the Egyptian city of Alexandria.

But this research team are convinced excavations at the ancient city of Taposiris Magna, which is marked by a temple that still stands today, will soon uncover the ancient couple’s resting place. Despite the fact researchers have been excavating the site since 2005, only a tiny percentage of the vast site has been explored.

The mummies were found in what is the first ever intact tomb to be opened at Taposiris Magna – an event that’s the subject of a Channel 5 documentary to be broadcast this week.

‘Although now covered in dust from 2,000 years underground, at the time these mummies would have been spectacular,’ Dr Glenn Godenho, a senior lecturer in Egyptology at Liverpool University, told the Guardian.

‘To be covered in gold leaf shows they would have been important members of society.’

One of the mummies was found wearing an image of a scarab, pained in gold leaf, symbolising rebirth. But the 200 coins bearing Cleopatra’s likeness links the pharaoh ruler directly to Taposiris Magna, which was founded in the third century BC.

The ‘prominent nose and double chin’ of the queen as depicted on the coins suggest she wasn’t as conventionally beautiful as the actresses that portrayed her on screen – most memorably by Elizabeth Taylor in the 1963 film ‘Cleopatra’.

Dr Godenho said that the tomb of Anthony and Cleopatra is expected to be a ‘way grander affair’ than this mummified couple.

‘Although we don’t know what Ptolemaic rulers’ tombs looked like because none have ever been firmly identified yet, it’s really unlikely that they’d be nondescript and indistinguishable from the burials of their subjects,’ he told MailOnline.

‘Add to that the fact that most consider the tomb of Cleopatra and Mark Antony to be in the vicinity of Alexandria rather than out here at Taposiris Magna, and all the evidence points to these not being royal mummies at all.’

Dr Kathleen Martinez, an academic from the Dominican Republic, is leading the dig at the Taposiris Magna temple. After working there for over 14 years, Dr Martinez and her colleagues are more convinced than ever Cleopatra’s tomb will be found there.

Dr Martinez is seen reacting to the opening of the newly-found mummies at Taposiris Magna in the Channel 5 documentary, which will broadcast on Thursday.

After an initial limestone slab is removed, she says: ‘Oh my god, there are two mummies … See this wonder.’

Cleopatra was Egypt’s last pharaoh and the ruler of the Ptolemaic Kingdom of Egypt, from 51 BC to 30 BC. Cleopatra and her Roman lover Mark Anthony may have been buried at the site 2,000 years ago because of her desire to imitate an ancient prophecy, Dr Martinez believes.

During her life, which ran from 69 BC to 30 BC, Cleopatra was known both as a seductress and as a captivating personality. She famously used her charms to first seduce Julius Caesar to cement Egypt’s alliance with Rome, and then to seduce one of his successors, Mark Anthony.

In order to fix herself and Anthony as rulers in the minds of the Egyptian people, she also worked hard to associate them with the myth of Isis and Osiris. According to the myth, Osiris was killed and hacked into pieces that were scattered across Egypt. After finding all of the pieces and making her husband whole again, Isis was able to resurrect him for a time.

Martinez believes Taposiris Magna was closely associated with the myth as the name means ‘tomb of Osiris’.

The inclusion of ‘Osiris’ could mean it was one of the places where his body was scattered in the story. After Mark Anthony killed himself following defeat to Octavian but before her own suicide, Cleopatra put detailed plans in place for them both to be buried there, in echoes of the myth, Dr Martinez thinks.

She previously told National Geographic: ‘Cleopatra negotiated with Octavian to allow her to bury Mark Antony in Egypt.

‘She wanted to be buried with him because she wanted to reenact the legend of Isis and Osiris.

‘The true meaning of the cult of Osiris is that it grants immortality. After their deaths, the gods would allow Cleopatra to live with Antony in another form of existence, so they would have eternal life together.’

Doubts have been cast on the theory, however, as other experts believe Cleopatra was hastily buried in Alexandria itself – the city from where she ruled Egypt until her death, believed to have been caused by snake venom.