Neanderthal Tooth from Iran Dated to Middle Paleolithic Period

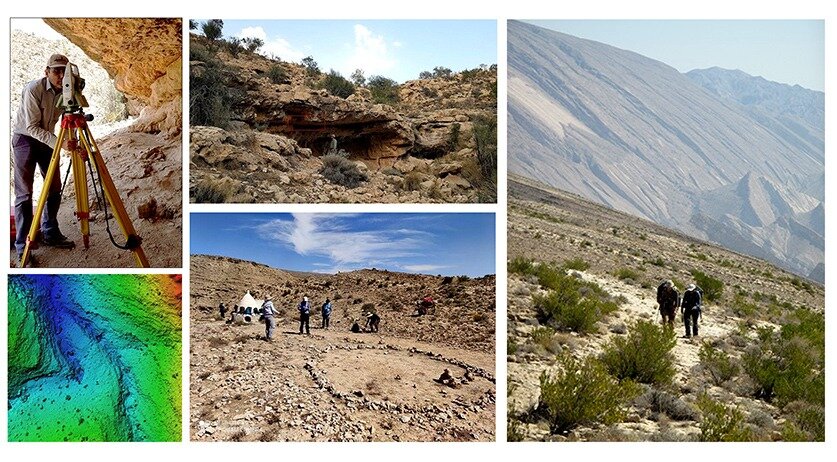

A new study conducted by a team of archaeologists and paleoanthropologists from Germany, Italy, Iran, and Britain delves into the discovery of an in-situ Neanderthal tooth, which was discovered in 2017 in a rock shelter, western Iran.

The research is described in a paper in the online journal PLOS ONE that was published last Thursday.

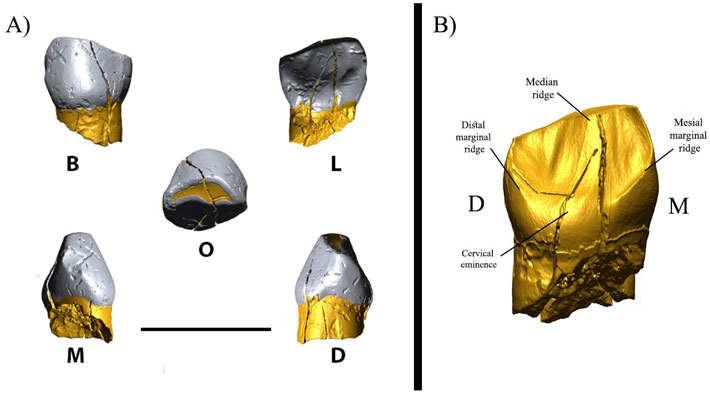

The tooth, which is a deciduous canine that belongs to a 6 years old child, was found at a depth of 2.5 m of the Baba Yawan shelter in association with animal bones and stone tools near Kermanshah.

The analysis that was performed by Stefano Benazzi, a physical anthropologist at the University of Bologna, Italy shows that the tooth has Neanderthal affinities. Stone tools discovered close to the teeth belong to the Middle Paleolithic period and a series of c14 dating suggests the tooth is between 41,000-43,000 years in an age which is close to the end of the Middle Paleolithic period when Neanderthal disappeared in the Zagros.

Fereidoun Biglari, a Paleolithic archaeologist at Iran National Museum, says “this recent discovery, along with other Neanderthal remains previously found in other parts of Zagros, including Shanidar Cave, Bisotun Cave, and Wezmeh Cave, indicate that Neanderthals were present in a wide geographical range of Zagros from northwest to west of this mountain range since at least 80,000 until about 40,000-45,000 years ago when they disappeared and Homo Sapiens populations spread into the region”.

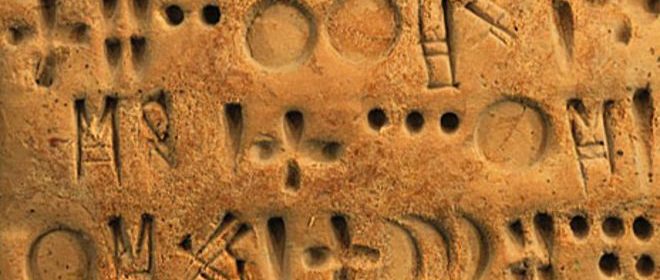

He added that “Association of Yawan Neanderthal tooth with Middle Palaeolithic stone tools known as Zagros Mousterian is a further confirmation of association of this stone tool industry with Neanderthals.

Such associations have been observed in Wezmeh where a Neanderthal premolar tooth and Zagros Mousterian tools were found in the same cave, and also in the Bisotun cave that was excavated in 1949 by C. Coon.

Bisotun produced a human partial radius that most likely belongs to a Neanderthal along with Zagros Mousterian lithics in Middle Paleolithic layers of the site”.

Huw Groucutt, a Paleolithic archaeologist at Max Planck Institute for the Science of Human History, commented on the datings provided for the Yawan tooth in his Twitter post “Dating sites like this, with small fragments of charcoal which are highly susceptible to movement and contamination, using the only radiocarbon is challenging”. He added “Nearly half of the radiocarbon dates from the site failed. I am rather dubious about the available dates for ‘Zagros Mousterian’ sites based only on C14. But he added “this is a great work, thousands of lithics found and a nice Neanderthal tooth. It is crucial though to use other dating techniques where possible.

The frequent ca. 45 ka ages in many parts of the world may reflect samples beyond the range of C14 with a bit of contamination.”

According to the researchers, Neanderthal extinction has been a matter of debate for many years.

New discoveries, better chronologies, and genomic evidence have done much to clarify some of the issues. This evidence suggests that Neanderthals became extinct around 40,000–37,000 years before the present (BP), after a period of coexistence with Homo sapiens of several millennia, involving biological and cultural interactions between the two groups.

However, the bulk of this evidence relates to Western Eurasia, and recent work in Central Asia and Siberia has shown that there is considerable local variation. Southwestern Asia, despite having a number of significant Neanderthal remains, has not played a major part in the debate over extinction.

Yawan is the second Neanderthal tooth that has been discovered in Iran. The first Neanderthal tooth was discovered in the Wezmeh cave near Kermanshah in 2001.

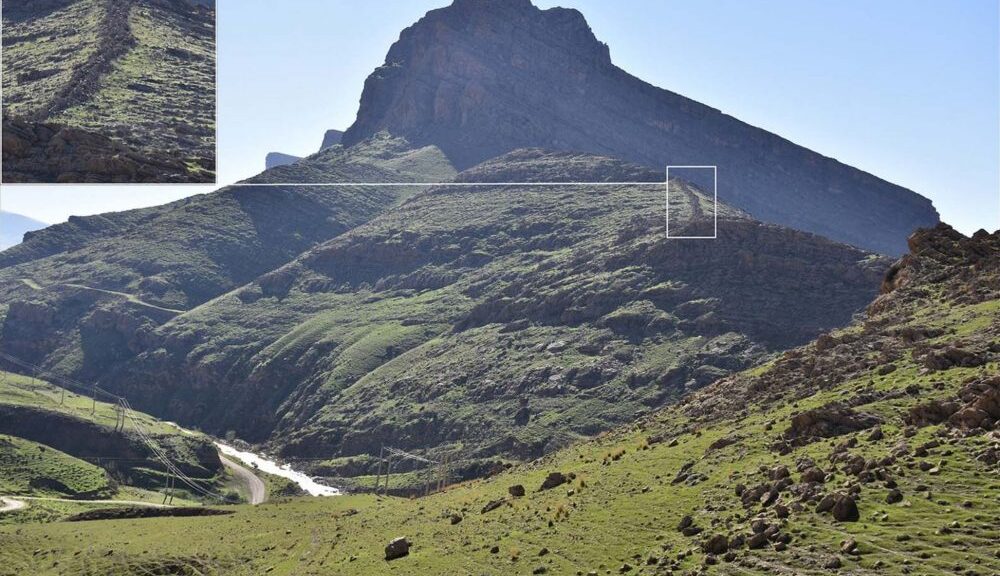

This cave is well-known for the discovery of a large number of animal fossils. A recent re-excavation of the cave by Fereidoun Biglari revealed stone tools made by Neanderthals, which shows that the cave was not just a den used by carnivores such as hyenas, lions, wolves, and leopards.

Moreover, the discovery of the third tooth of a 5-7 years old Neanderthal child was announced by a joint Iranian-French team that was discovered in Qal-e Kord near Qazvin in 2019.

These discoveries show that Iran has a rich paleoanthropological record and the country can produce important data in the future.