Archaeology breakthrough: Second ‘hidden pyramid’ discovered inside iconic Mayan structure

Archaeologists have confirmed that the massive Kukulkan pyramid in eastern Mexico – one of the most iconic pyramids in the world – was built like a Russian nesting doll, with the discovery of two smaller pyramids hidden within its walls.

The first of the hidden pyramids was discovered back in the 1930s, built within the walls of the colossal Kukulkan tomb. Now an even smaller pyramid has been found inside that one – and the discoveries might not stop there.

“To make matters more complicated, the third Russian doll moving in may actually be one of a set of several small dolls rattling around inside the same shell.

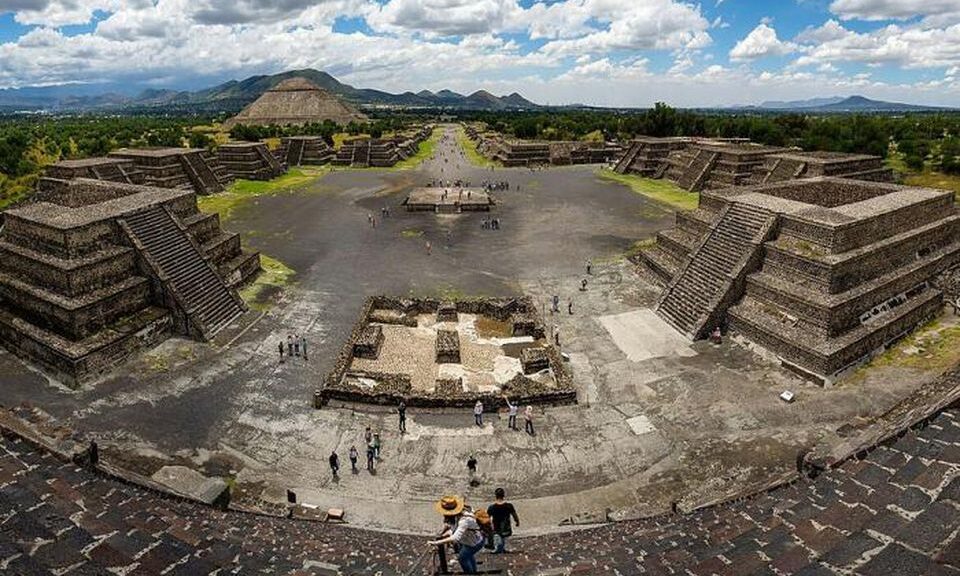

We just do not know,” anthropologist Geoffrey Braswell from the University of California, San Diego, who was not involved in the study, told The Associated Press. Built sometime between the 9th and 12th centuries, the Kukulkan pyramid is the centrepiece of the vast Chichen Itza complex in the Mexican state of Yucatán.

Also known as El Castillo (meaning “the castle”), this colossal pyramid features 364 steps – one for every day of the year in the Maya calendar system – and stands 24 metres (79 feet) tall. A 6-metre-high (20-foot) temple sits on top of the pyramid and was dedicated to the featured serpent god, Kukulkan.

Back in 1931, archaeologists began investigating the insides of the pyramid, with suspicions that it could be hiding the remains of a much older version – something that was widely disbelieved at the time.

Over the course of the next five years, they discovered a room nicknamed the hall of offerings, containing a giant Chacmool statue, its nails, teeth, and eyes inlaid with mother of pearl.

They also found a room called the chamber of sacrifices, containing two carefully arranged rows of human bones, and an elaborate red jaguar statue, encrusted with 74 jade inlays for spots, and jade-studded eyes.

The researchers soon realised that there was a larger, much older pyramid hidden below and inside the Kukulkan pyramid, and it stands roughly 33 metres tall (108 feet).

Now, archaeologists have completed their latest investigation of that internal pyramid using a non-invasive imaging technique called tri-dimensional electric resistivity tomography, and report the discovery of a 10-metre-tall (33-foot) pyramid hidden inside the larger two.

At this stage, it’s not clear if this the same structure archaeologists detected back in the 1940s but couldn’t confirm – or something else entirely.

Oddly enough, it appears to have been built above a water-filled sinkhole called a cenote, which researchers detected under the Kukulkan pyramid just last year.

It’s not clear if the Maya knew of the cenote themselves, but the fact that the pyramids were built directly on top of it, and that Kukulkan was a god of water (among other things), suggests that maybe they did.

“The structure that we have found, the new structure, is not completely in the centre of the Kukulkan pyramid. It is in the direction where the cenote is,” Rene Chavez Segura, from the National Autonomous University of Mexico, told CNN.

“This could either confirm or hypothesise that the Mayans when they built this structure that they knew of the existence of this cenote.”

According to Segura and his team, the smallest pyramid was likely built between 550 and 800 AD. The middle structure has between 800 and 1000 AD, while the outer one was finished between 1050 and 1300 AD.

The researchers are yet to publish their findings, so these dates and the pyramid’s structure will still need to be verified by independent teams, but it’s hoped that further investigations will continue, so we can figure out if there are even more pyramids hidden inside.

“If this could be investigated in the future, this structure would be significant, because it would speak to the first few periods of habitation of the site and would provide information about how the settlement developed,” Denisse Argote from Mexico’s National Institute of Anthropology and History told CNN.