Unpredictable Rainfall May Have Helped Destabilized Ancient Maya Societies

Reduced predictability of seasonal rainfall might have played a significant role in the disintegration of Classic Maya societies about 1,100 years ago. The decline in seasonal predictability potentially destabilized Classic Maya societies in a new study recently published in Communications Earth & Environment.

University of New Mexico archaeologist Keith Prufer is among the authors, along with colleagues at the Potsdam Institute for Climate Impact Research (PIK) and Potsdam University. The findings may have significance for populations in the region facing climate change today.

The research team studied variations in stable isotope signatures from a stalagmite collected in a cave in Belize near an archaeological site in the former heartland of the Maya. The carbon and oxygen isotope ratios are sensitive recorders of local and regional rainfall dynamics.

This paper is a continuation of 18 years of research by Prufer, UNM colleagues, and an international team of scientists into the past climate in the Belize tropics.

Prufer has been a principal investigator for the research program, with funding from the National Science Foundation and the Alphawood Foundation.

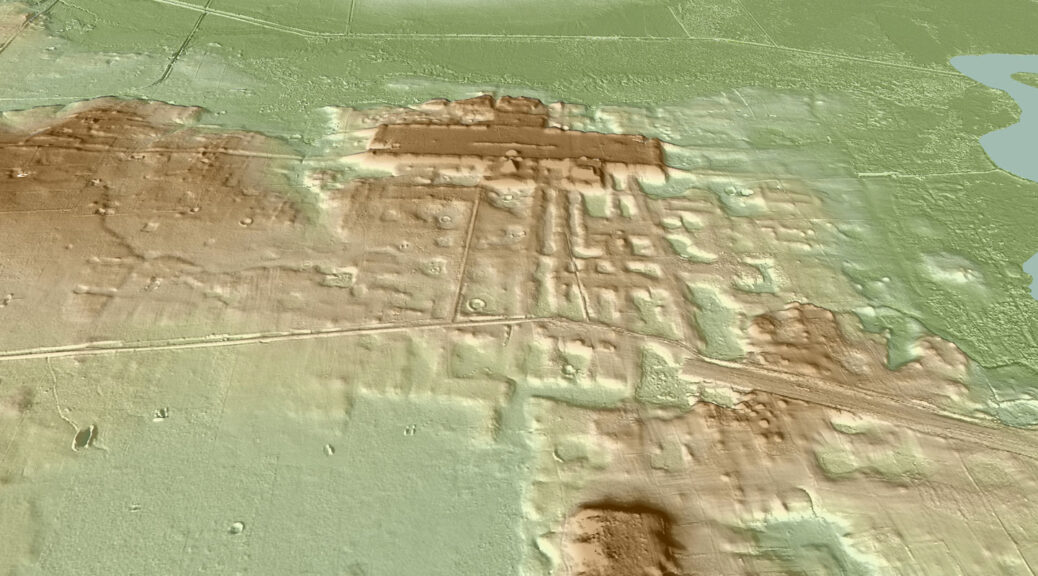

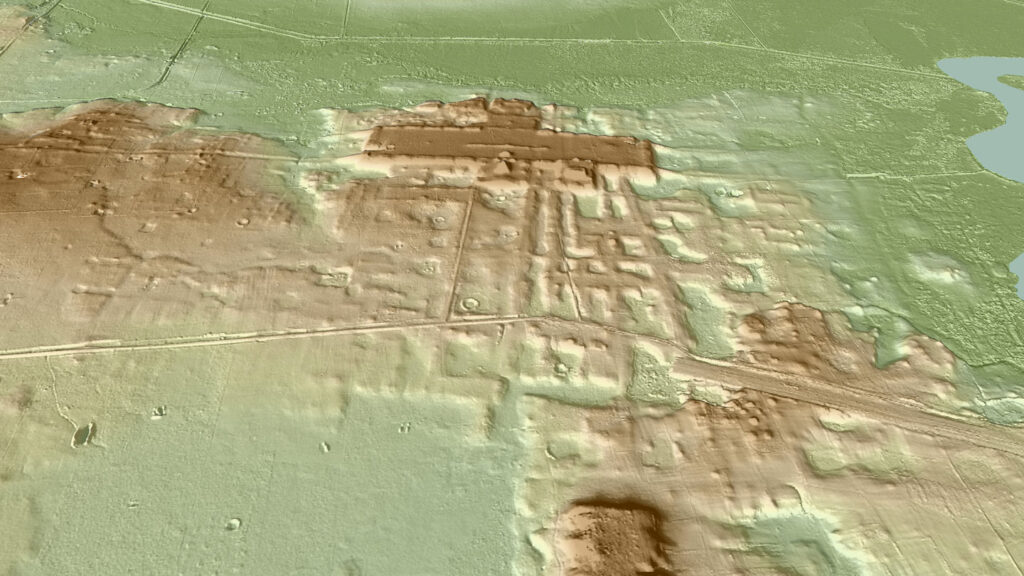

“The climate record was generated from a cave called Yok Balum, located near the ancient Maya city of Uxbenká. That ancient city figures prominently in this article and is important because it is the closest to the site of the climate data and because of two decades of research there exploring the timing of the collapse,” Prufer explained.

This paper is a collaboration with the Potsdam Institute for Climate Impact Research in Germany to get advanced time-series modeling to understand the patterning of seasonal variation. The lead at PIK, Tobias Braun, used this study for his dissertation.

Also included in the research team from UNM are Ph.D. candidate student Erin Ray and Victor Polyak, a senior research scientist in the UNM Department of Earth and Planetary Science. Ray worked to assemble the cultural data, such as the data that records the dynastic history of the Maya from their hieroglyphs, and demographic data. Polyak originally developed the high-precision chronology for the climate and seasonality records.

“A key ingredient for Maya agriculture was the timely arrival of sufficient rainfall. Farming in subtropical Central America is tough because freshwater is only available during the summer rainy season.

Changes of onset and intensity of the rainy season can have serious repercussions for Central American societies,” Braun noted in a PIK press release about the newly published study. While most scientists agree that repeated intense droughts were one of the key factors that led to the fragmentation of urban centers and population dispersal in lowland Maya societies, evidence at seasonal time scale was so far missing. And this is exactly what the study takes into focus.

The significance of this record is three-fold, according to Prufer.

“First, it is a novel climate record for the American tropics with such high resolution – one to seven samples per year over a 1,600-year period − allowing us to look at changes in seasonality from year to year. It is also the first such record to incorporate advanced time series modeling to evaluate seasonal variation in the neotropics and link those changes directly to quantitative cultural records,” Prufer explained.

Second, the research sheds new light on an enduring question in Maya archaeology: What caused the population decline and disintegration of political institutions at the end of the Classic Period between 250 and 850 CE?

Prufer and his colleagues found that changes in seasonality would have challenged food production in this region where all agriculture is directly dependent on rainfall by making the timing for planting harvesting much more difficult − or impossible − to predict from year-to-year.

“The collapse was significant,” he noted. “Over the course of perhaps 100 to 150 years, populations as high as 5 to 10 million people declined by as much as 60 to 70 percent, and a complete form of governance was abandoned.”

Third, this research has significance for farming today. The past is an indication of what might be expected in a dire future.

“With modern global climate change, seasonality patterns are again far less predictable than they were only a couple of decades ago,” Prufer pointed out. “This is forcing modern Maya farming communities − and everyone else − to rethink how they produce food and how to achieve food security, considering their dependence on the timing of the rainy season and the seasonal distribution of rainfall, which is no longer predictable.

“This is important because farming requires both traditional knowledges of when to clear fields and plant, as well as a reliable amount of rainfall each season. When this breaks down, it causes food shortages and human suffering. This case study has implications for collective responses to climate change across the global tropics, a region that feeds over 2 billion people.”