Lasers reveal sites used as the Americas’ oldest known star calendars

Olmec and Maya people living along Mexico’s Gulf Coast as early as 3,100 years ago built star-aligned ceremonial centers to track important days of a 260-day calendar, a new study finds.

The oldest written evidence of this calendar, found on painted plaster mural fragments from a Maya site in Guatemala, dates to between 300 and 200 B.C., nearly a millennium later (SN: 4/13/22). But researchers have long suspected that a 260-day calendar developed hundreds of years earlier among Gulf Coast Olmec groups.

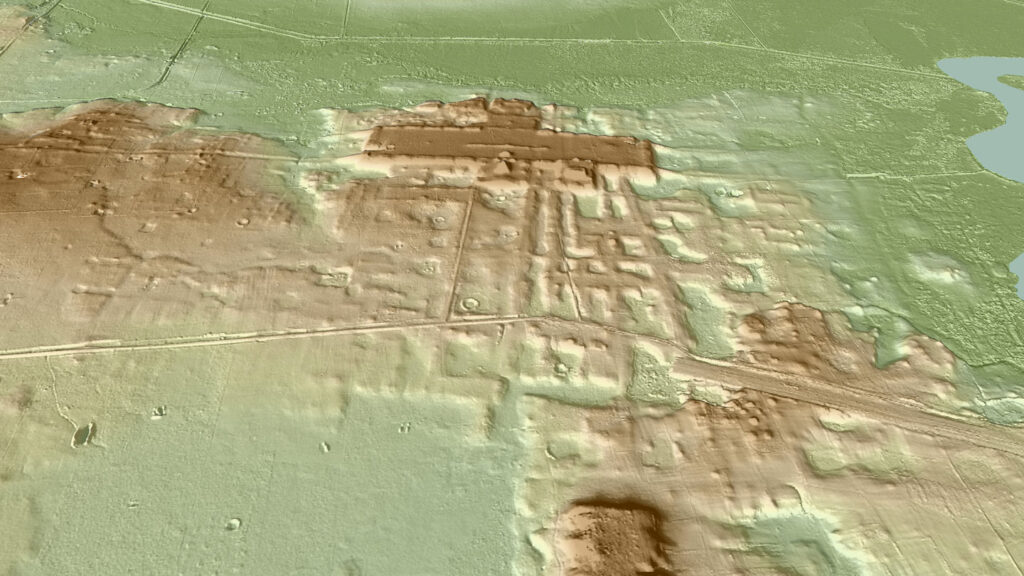

Now, an airborne laser-mapping technique called light detection and ranging, or lidar, has revealed astronomical orientations of 415 ceremonial complexes dating to between about 1100 B.C. and A.D. 250, say archaeologist Ivan Šprajc and colleagues.

Most ritual centers were aligned on an east-to-west axis, corresponding to sunrises or other celestial events on specific days of a 260-day year, the scientists report January 6 in Science Advances.

The finding points to the earliest evidence in the Americas of a formal calendar system that combined astronomical knowledge with earthly constructions. This system used celestial events to identify important dates during a 260-day portion of a full year.

“The 260-day cycle materialized in Mesoamerica’s earliest known monumental complexes [and was used] for scheduling seasonal, subsistence-related ceremonies,” says Šprajc, of the Research Center of the Slovenian Academy of Sciences and Arts in Ljubljana. “We cannot be certain exactly when and where it was invented.”

Some of the oldest ceremonial centers identified by lidar clearly belong to the Olmec culture, but others are hard to classify, says archaeologist Stephen Houston of Brown University in Providence, R.I., who did not participate in the new study.

Olmec society dates from around 3,500 to 2,400 years ago. Links between the Olmec and later Maya culture, known best for Classic-era cities and kingdoms that flourished between roughly 1,750 and 1,100 years ago, are unclear. But Classic Maya inscriptions and documents also reference the 260-day calendar.

Mobile groups in Mesoamerica, an ancient cultural region that extended from central Mexico to Central America, may have scheduled large, seasonal gatherings using the 260-day calendar long before it gained favor among Classic Maya kings, Šprajc and colleagues suggest.

The same calendar may also have marked days of important agricultural activities or rituals as maize cultivation spread in Mesoamerica starting around 3,000 years ago, they add. Some Maya communities still use a 260-day calendar to organize maize cultivation and schedule agricultural rituals.

Previous lidar data indicated that ceremonial centers based on a common blueprint appeared at many Olmec and Maya sites along Mexico’s Gulf Coast by about 3,400 years ago (SN: 10/25/21). Only now has the calendrical significance of ceremonial centers’ alignments become apparent.

The most common architectural alignment detected in the new study corresponded to the position of sunrises on February 11 and October 29 when complexes were in use, separated by 260 days. These complexes faced east toward a point on the horizon where the sun rose on those two days.

Another frequent orientation matched sunrises separated by 130 days, or half of the 260-day count.

A minority of ceremonial complexes were aligned with dates of solstices (longest and shortest days of the year), quarter days (the midpoint of each half of the year) or lunar cycles in the 260-day year. Other centers tracked the position of Venus, a star associated with the rainy season and maize farming.

Sunrises or sunsets recorded at ceremonial centers were typically separated by multiples of 13 or 20 days. Aside from representing basic mathematical units of a 260-day year, the numbers 13 and 20 have long been associated with various gods and sacred concepts among Maya people and other Mesoamerican groups, Šprajc says.

Future excavations at lidar-detected ceremonial complexes can investigate whether ancient groups formally dedicated certain structures to specific days in the 260-day year, Houston says.