New Huge Viking Ship Discovered By Radar In Øye, Norway – What Is Hidden Beneath The Ground?

A new Viking Age ship has been discovered by archaeologists in Norway during a ground-penetrating radar (GPR) survey. This exciting find reveals a huge Viking boat buried beneath the ground in Øye, in Kvinesdal.

This archaeological discovery is highly significant not only because Viking ship burials are rarely found, but also due to the fact that Kvinesdal was once the home to one of Southern Norway’s largest known burial sites from the Iron and Viking Ages.

Archaeologists from the Norwegian Institute for Cultural Heritage Research (NIKU) said the ancient boat was spotted while researchers conducted geophysical surveys in the area as part of the road-building project E39 led by Nye Veier.

The surveys are a part of the research project “Arkeologi på Ney Veier” (Archaeology on new roads). Based on preliminary reports, archaeologists estimate the Viking boat to be between 8 to 9 meters long.

Niku researchers inform that in addition to the boat burial there are traces of several other burial mounds.

At present, it is still unknown how much of the Viking boat remains. Excavations must be carried out and hopefully, the new road project will not interfere with archaeologists’ work. As previously explained on AncientPages.com, Viking burials were very complex which is the reason why so few boat burials have been unearthed.

When a great Viking chieftain died, he received a ship burial. This involved placing the deceased on the ship, sailing him out to sea, and setting the Viking ship on fire. People could watch flames dance high in the air as they embraced the mighty warrior on his way to the afterlife.

By modern standards, it might sound crude, but Viking burials were intended to be a spectacular ritual. Viking funeral traditions involved burning ships and complex ancient rituals. Based on discovered archaeological evidence it seems that the funeral boat or wagon was a practice reserved for the wealthy.

This type of burial was not common however and was likely reserved for sea captains, noble Vikings, and the very wealthy. In Old Norse times, boats proper boats took several months to construct and would not have been wasted without a valid cause or a suitable amount of status.

Another option was that the Vikings was burned, and cremation was rather common during the early Viking Age. Ashes were later spread over the waters. The vast majority of the burial finds throughout the Viking world are cremations.

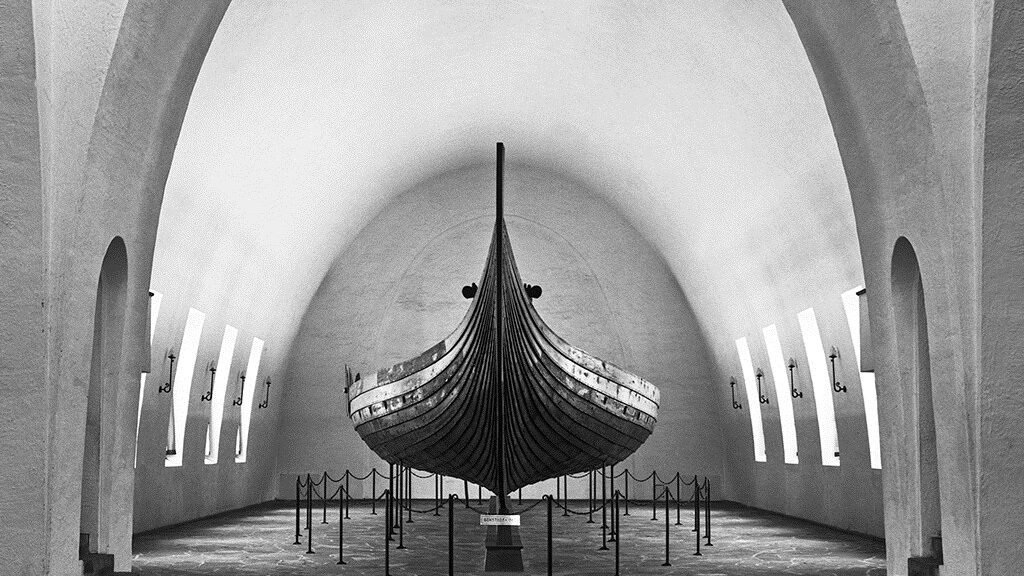

Archaeological discoveries such as the finding of the magnificent Gokstad Viking ship discovered in 1880 offer more insight into the world of the Vikings. When scientists re-opened and examined the grave in 2007 we could finally learn more about the man who became known as one of the most famous Vikings in Norway – the Gokstad Viking Chief and his remarkable ship.

The Gokstad ship was built in about 850, at the height of the Viking period. In those days there was a need for ships that could serve many purposes, and the Gokstad ship could have been used for voyages of exploration, trade, and Viking raids. The ship could be both sailed and rowed. There are 16 oar holes on each side of the ship. With oarsmen, steersmen, and lookout, that would have meant a crew of 34.

In recent years there have been exciting reports of unearthed Viking Age burial ships in Sweden and Norway.

The giant Gjellestad Viking ship burial in Norway found some years ago has given a unique opportunity to see the world through the eyes of the Vikings.

The discoveries were made by archaeologists from the Norwegian Institute for Cultural Heritage Research (NIKU) with technology developed by the Ludwig Boltzmann Institute for Archaeological Prospection and Virtual Archaeology (LBI ArchPro).

– We are certain that there is a ship there, but how much is preserved is hard to say before further investigation”, Morten Hanisch, county conservator in Østfold said at the time.

Later, scientists using modern technology put together an outstanding virtual tour of the Gjellestad Viking ship burial site, allowing viewers to see what the place looked like in ancient times.

The new radar discovery in Øye is promising and hopefully, researchers will be able to unearth and examine the remains of the Viking ship. Once they accomplish this, we will learn more about the boat and its history. Maybe remains of a Viking Chief will also be found.