Human spines on sticks found in 500-year-old graves in Peru

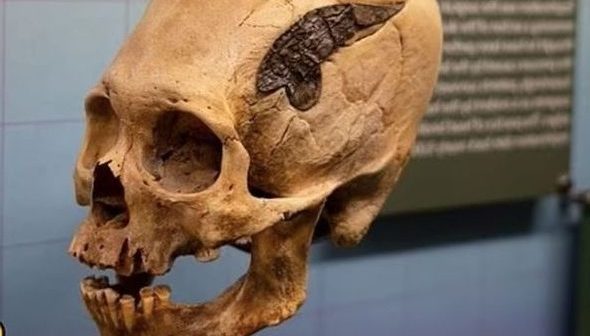

Hundreds of years ago, Indigenous people in coastal Peru may have collected the scattered remains of their dead from desecrated graves and threaded reed posts through the spinal bones.

Scientists recently counted nearly 200 of these bone-threaded posts in stone tombs in Peru’s Chincha Valley, and they suspect that the practice arose as a means of reassembling remains after the Spanish had looted and desecrated Indigenous graves.

Archaeologists investigated 664 graves in a 15-square-mile (40 square kilometres) zone that contained 44 mortuary sites. They documented 192 examples of posts threaded with vertebrae.

The researchers then measured the amount of radioactive carbon in the bones and reed posts. Radioactive carbon accumulates when an organism is alive but decays to nitrogen at a constant rate once the organism is dead. So based on the amount of this carbon, the scientists could estimate when the posts were assembled.

Their analysis placed the vertebrae and posts between A.D. 1450 and 1650 — a time when the Inca Empire was crumbling and European colonizers were consolidating power, the researchers wrote in a new study.

This was a period of upheaval and crisis in which Indigenous tombs were frequently desecrated by the Spanish, and Chincha people may have revisited looted tombs and threaded spinal bones on reeds in order to reconstruct disturbed burials, said lead study author Jacob Bongers, a senior research associate of archaeology with the Sainsbury Research Unit at the University of East Anglia in the United Kingdom.

“The fact that there’s 192 of these and that they’re widespread — we find these throughout the Chincha Valley — it means on one level that multiple groups of people coordinated and responded in a shared way, that this interesting practice was deemed the appropriate way of dealing with disturbed bodies of the dead,” Bongers told Live Science.

Most of the vertebrae on posts were found in and around large and elaborate stone tombs, called chullpas, that typically held multiple burials; in fact, one chullpa contained remains from hundreds of people, Bongers said.

The people who performed the burials were part of the Chincha Kingdom, “a wealthy, centralized society that dominated Chincha Valley during the Late Intermediate period, which is the period that precedes the Incan Empire,” Bongers explained.

The Chincha Kingdom once had a population numbering around 30,000, and it thrived from around A.D. 1000 to 1400, eventually merging with the Inca Empire toward the end of the 15th century. But after the Europeans arrived and brought famines and epidemics, Chincha numbers plummeted to just 979 heads of household in 1583, according to the study.

Historic documents record accounts of Spaniards frequently looting Chincha graves across the valley, stealing gold and valuable artefacts, and destroying or desecrating remains.

For the new study, the researchers closely examined 79 bone-threaded posts, each of which represented a collection of spinal bones from an adult or from a child.

Most posts held bones belonging to a single individual, but the spines were incomplete, with most of the bones disconnected and out of order. This suggested that the threading was not performed as a part of the original burial. Rather, someone gathered and threaded the spinal vertebrae after the bodies had decomposed — and perhaps after some of the bones were lost to looting, the study authors reported.

And because Andean cultures valued preserving the integrity and completeness of a dead body, the likeliest explanation is that Chincha people revisited looted graves and reconstructed the scattered remains in this way to try and restore some semblance of wholeness to remains that had been dispersed and desecrated.

“When you look at all data we gathered, all of that supports the model that these were made after these tombs had been looted,” Bongers said.

Ancient mortuary practices, such as this bone threading, provide valuable clues about how long-ago communities dealt with their dead, but they also shed light on how people defined their identities and culture through their relationships with the dead, Bongers told Live Science.

“Mortuary practices arguably are what make us human — this is one of the key distinguishing features of our species. So, by documenting mortuary practices, we’re learning diverse ways of how people showcased their humanity.”

The findings were published on Feb. 2 in the journal Antiquity.