1,000-Year-Old Buffalo Jump Discovered in Wyoming

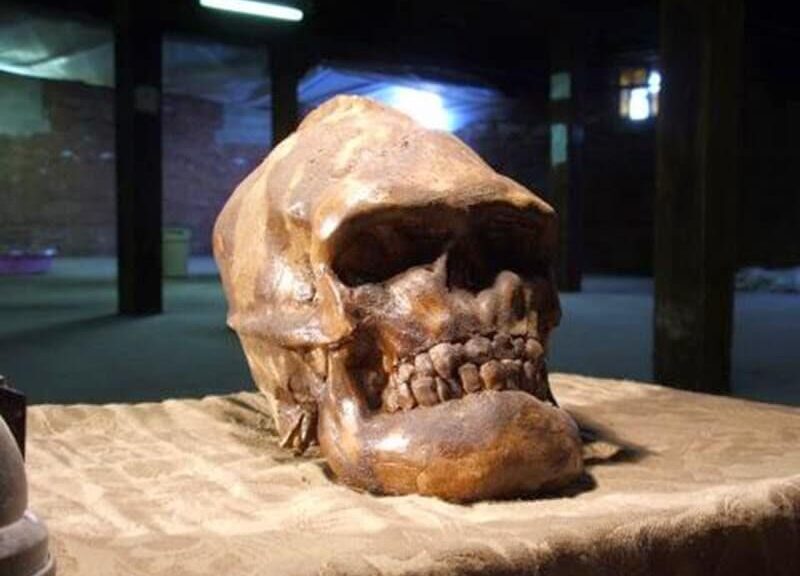

For Curt Ogburn and Wade Golden, the journey to the excavation of the Ogburn-Golden Bison Jump near Baggs began almost 30 years ago, when the two high school students first found an old bison skull on state land.

Wade and I were like brothers,” Ogburn said. We found all kinds of stuff out in the desert, and it was our playground. One day in 1991, Ogburn and Golden were out in the hills, doing the thing so many Wyoming teenagers do: scaling rocks, climbing hills, and exploring.

“We were hiking around the Red Desert west of Baggs, and found a buffalo skull,” Golden said. “We thought, ‘Wow, this is cool,’ so we picked it up and took it back to the high school science lab where we gathered around and looked at it… That was it.”

In about 2008, Golden started wondering — could he find that site again?

“As I was hiking in, I started finding artifacts. I found a lot more buffalo skulls and a lot more bones all around,” Golden said. Golden said that after a few attempts to contact the Wyoming State Archaeologist, Spencer Pelton, who took the job in November, agreed to investigate.

“I get a lot of calls, but this one seemed promising,” Pelton said, adding that the two first headed to the site in late June.

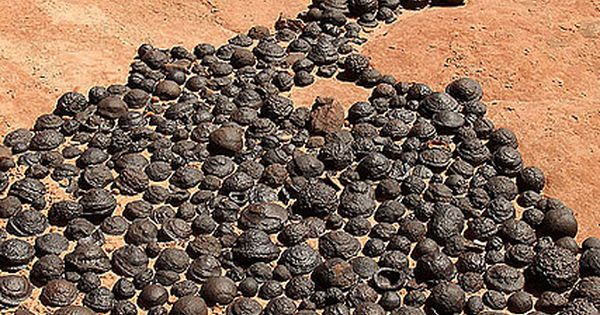

“We discovered this was an archaeology site used to kill bison, and it was used between around 1,000-1,500 years ago,” he said. “This particular site is — the best way to put it is that there is no way that bison bone would have ended up where it was without humans having a role in it. These bison bones are perched upon some pretty steep, cliffy areas, and it is not in a place where you would expect an animal to die naturally.”

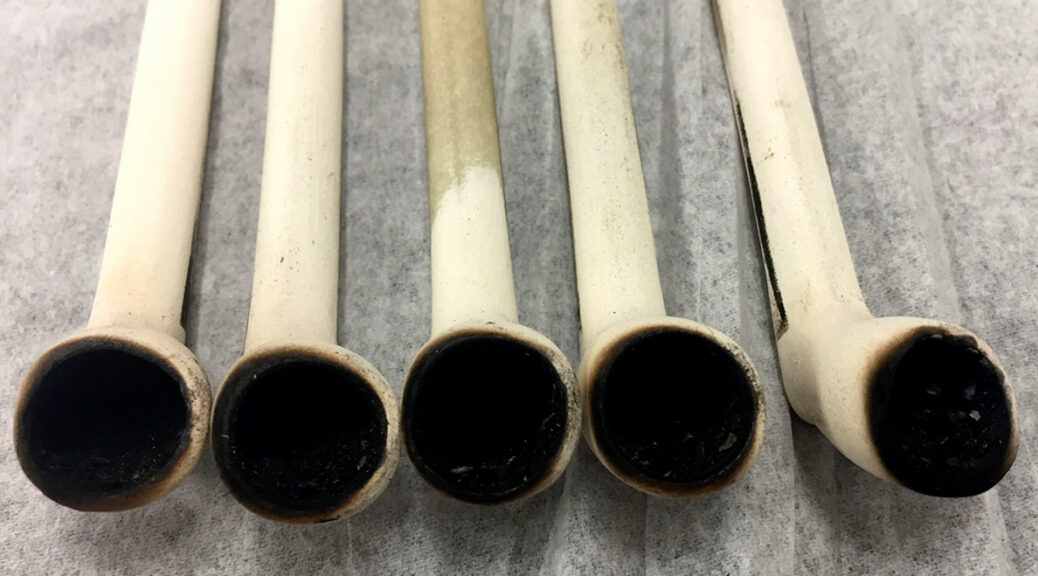

For what were the earliest users of the bow and arrow, the journey to the area started 1,000-1,500 years ago. This was a millennium before the introduction of the horse to North America, around the time people transitioned from using a spear, or atlatl, to the bow and arrow. Several arrow points directly associated with the bones have also been discovered.

“These are probably some of the first people to use the bow and arrow,” Pelton said. “The site wasn’t so much of a cliff, but a steep embankment where the animals would become increasingly confined near steep, broken terrain. As these bison got more and more confined, it got easier for people to kill them.”

Bison hunting was a very dangerous endeavor, he said.

“To some extent, hunting is still dangerous compared to our day-to-day lives,” Pelton said. “But especially in prehistoric days, chasing these giant animals with stone tools, there is not a lot of room for error in that process.”

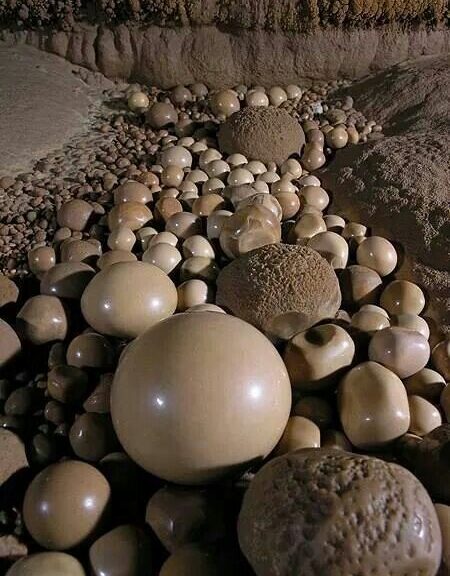

Landscape at any given site is unique, but the bones at the Ogburn-Golden Bison Jump were preserved in a mudstone layer of rock.

“The bones became incorporated with the sediments in this area, which have gradually eroded down to where we found them today,” Pelton said. “This place is in a unique setting. I have never actually seen anything like it.”

Slopes are typically not great for preservation because they’re constantly eroding, but in this case, the bedrock mudstone preserved the bones in just the right way, Pelton said. Wyoming likely had its prehistoric population peak around 1,000-1,500 years ago, when people lived in semi-permanent seasonal camps that they would return to on an annual basis. There is evidence that people in the area had a complex, large society with an extensive trade network reaching the Pacific Ocean.

The exact location of the Ogburn-Golden Bison Jump is confidential for the time being, to preserve the opportunity for study.

“It is really important that when we find an archaeology site of some significance that one, there is confidentiality involved,” Pelton said. “We don’t want folks collecting things because that would impact our ability to interpret how the site was used, and two, this site, in particular, doesn’t lend well to public interpretation. It is in a really dangerous spot, so how we handle something like this is we conduct an excavation, write up our findings and establish an exhibit in a local museum.”

For Golden, preservation is first and foremost.

“This is history that should be shared with everyone,” he said. “It is very neat. I knew immediately, once I started finding artifacts, what it was, and the importance of it. Ogburn said that to a 16-, 17-year-old kid, finding the bison skull was a novelty, but it is only now that he can fully appreciate what he and his best friend stumbled on three decades ago.

“We knew what it was, but we didn’t know the extent until the State Archaeologist came to look at the site,” he said. “Wade has always been the geologist, archaeologist type. We grew up together since we were four years old, and I used to tease him that he could get out of a car in the middle of a Walmart parking lot and trip over an arrowhead. He is that kind of guy. He is lucky — but he knows what he is looking for.”

Ogburn’s own son is 10 now and loves Wyoming’s history. That his name will forever be on a bison jump in Carbon County — that is pretty amazing.

“I am just so glad Wade kept up with this. My son is 10, and he loves this kind of thing,” Ogburn said. “It is pretty cool.”