Researchers Discovered Wreckage of a Schooner that Sank in Lake Michigan in Late 1800s

Maritime historians from the Wisconsin Underwater Archeology Association discovered the wreckage of a schooner that sank in Lake Michigan in the late 1800s.

The Margaret A. Muir – a 130-foot, three-masted ship built in 1872 – was found under about 50 feet (15 meters) of Lake Michigan water off Algoma, Wisconsin, according to a Wisconsin Underwater Archaeology Association (WUAA) news release.

The Muir was built at Manitowoc, Wisconsin by the Hanson & Scove shipyard for Captain David Muir. It was intended primarily for the Great Lakes grain trade, although it carried many diverse cargoes, frequenting all five Great Lakes over her 21-year career.

The ship was en route from Bay City, Michigan, to South Chicago, Illinois, with a cargo of bulk salt. It had almost reached Ahnapee, which is now known as Algoma, when it sank during a storm on the morning of Sept. 30, 1893.

According to the Wisconsin Underwater Archeology Association, the six-member crew and Captain David Clow made it to shore in a lifeboat, but Clow’s dog went down with the ship. Captain Clow, a 71-year-old Lake veteran, had seen many wrecks in his day, but exclaimed “I have quit sailing, for water no longer seems to have any liking for me.”

The Captain was particularly grieved at the loss of his dog, described as “an intelligent and faithful animal, and a great favorite with the captain and crew.” The Captain remarked, “I would rather lose any sum of money than to have the brute perish as he did.”

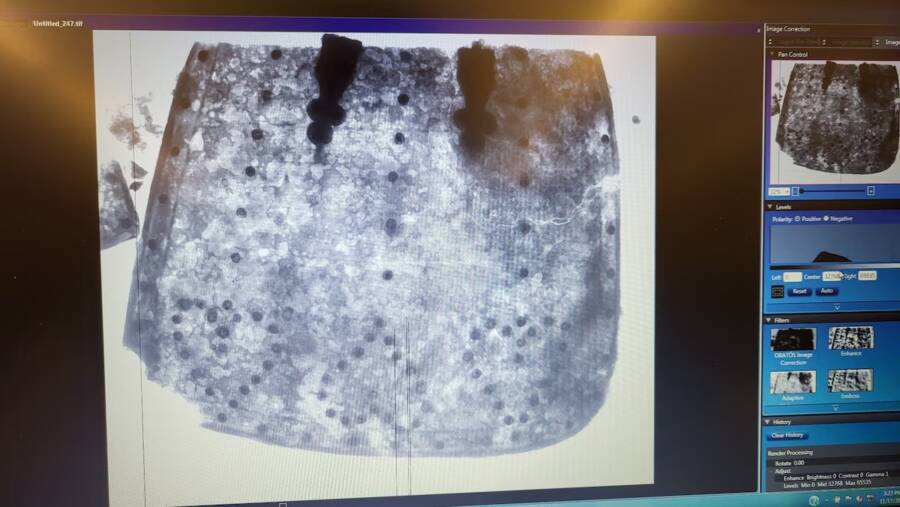

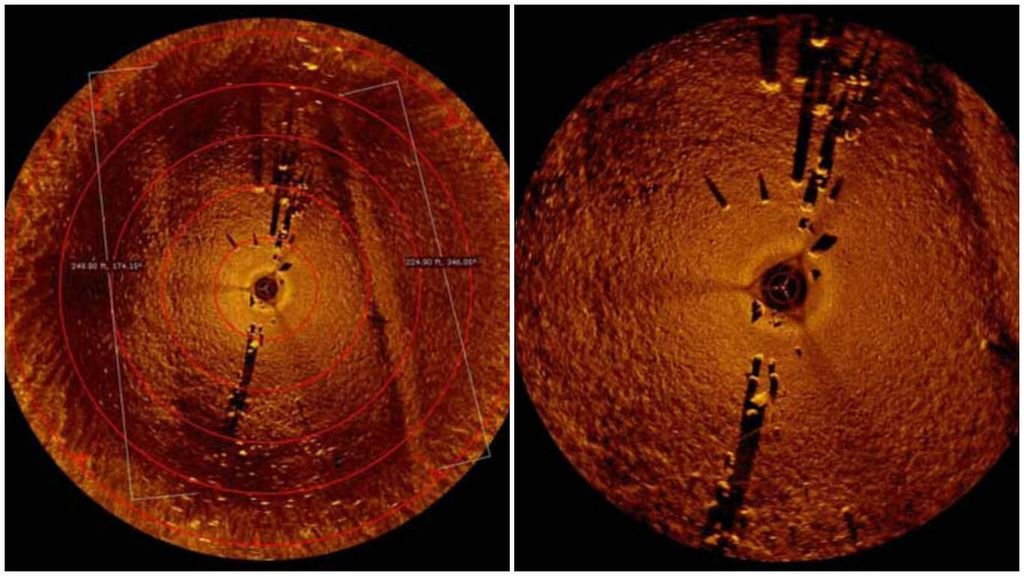

The team, including Brendon Baillod, Robert Jaeck and Kevin Cullen used historical records as well as a high resolution side scanning sonar to locate the vessel, finding its remains on May 12th, 2024.

The Margaret A. Muir was lost to history until Baillod began compiling a database of Wisconsin’s missing ships around twenty years ago. The Muir stood out as being particularly findable.

In 2023, Baillod approached the Wisconsin Underwater Archeology Association to undertake a search for the vessel, narrowing the search grid to about five square miles, using historical sources.

Baillod, Jaeck and Cullen were on their final pass of the day and in the process of retrieving the sonar when they ran over the wreck in approximately fifty feet of water only a few miles off the Algoma Harbor entrance. It had lay undetected for over a century, despite hundreds of fishing boats passing over each season.

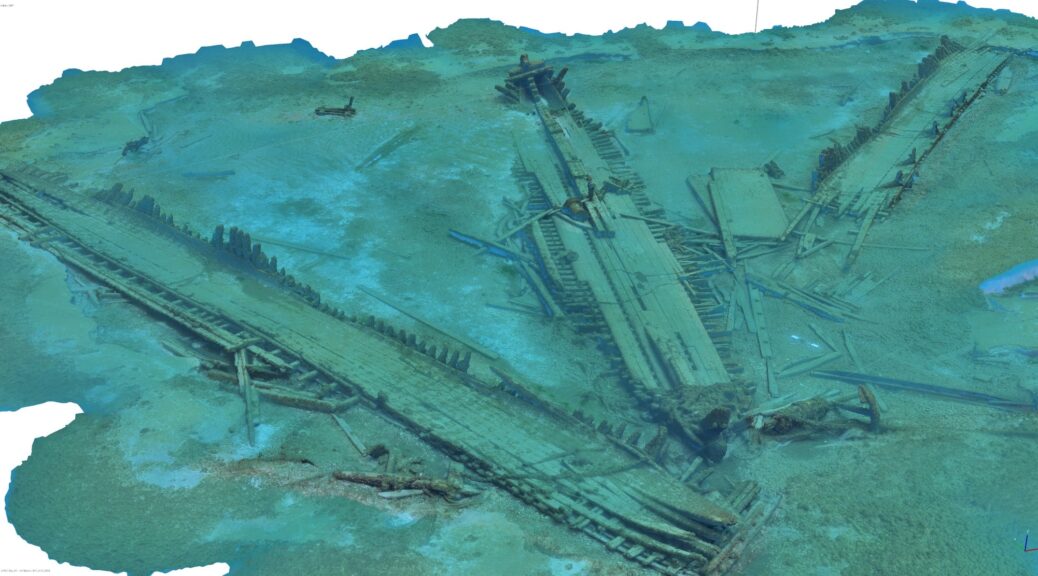

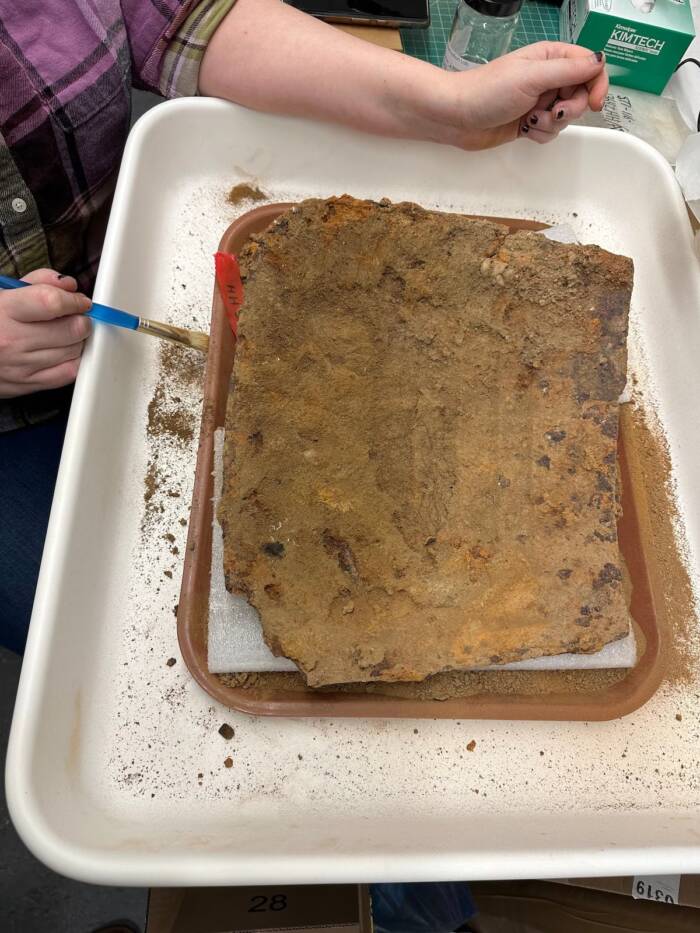

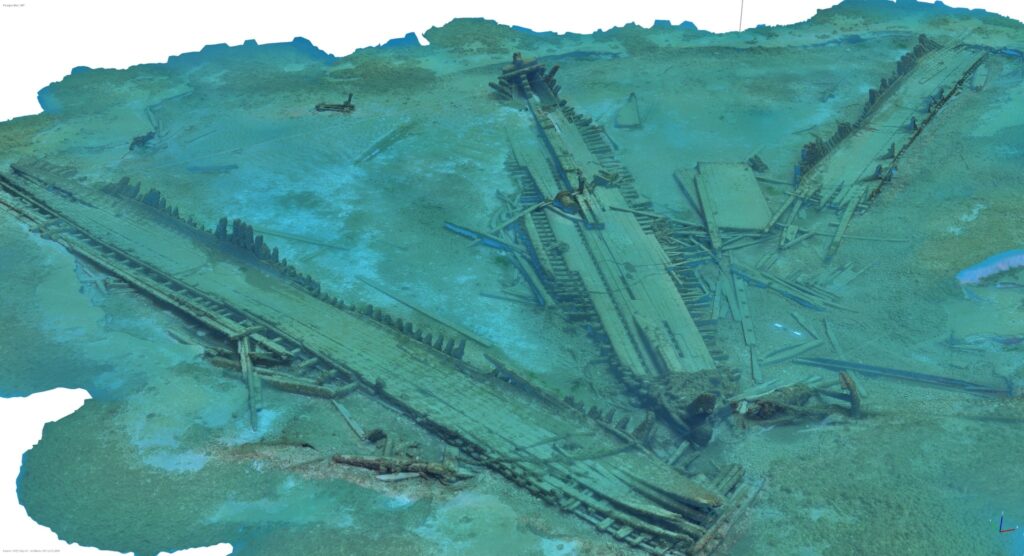

After informing Wisconsin State Maritime Archeologist Tamara Thomsen of the discovery, the team worked for weeks to gather thousands of high-resolution photos of the location. Zach Whitrock then used these photos to create a 3D photogrammetry model of the wreck site, which enables virtual site exploration.

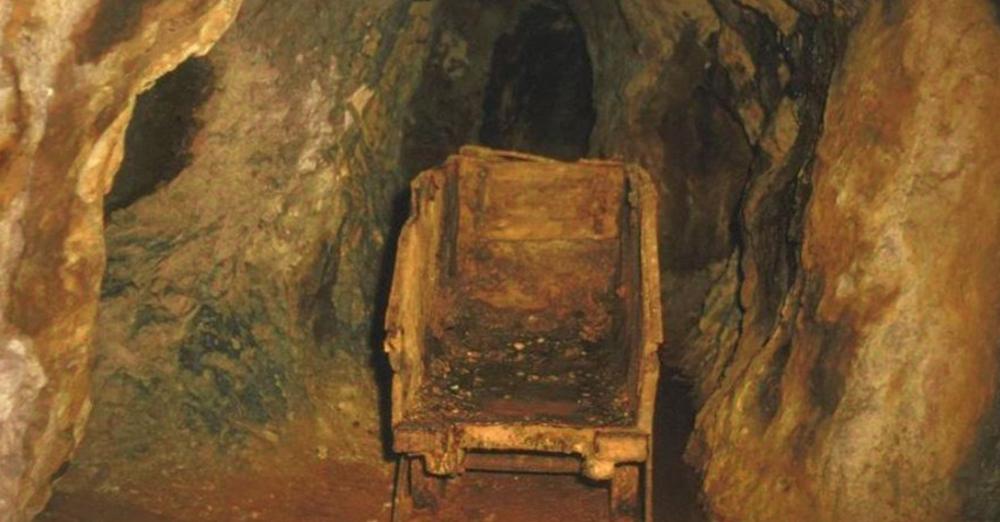

The vessel is no longer intact, its sides having fallen outward after deck collapsed, but all its deck gear remains, including two giant anchors, hand pumps, its bow windlass and its capstan.

The Wisconsin Underwater Archeology Association now plans to work with the Wisconsin Historical Society’s Maritime Archeology Program to nominate the site to the National Register of Historic Places. If accepted, it will join the schooner Trinidad, which the team located in deep water off Algoma in June of 2023.