Genetic Study Establishes Native Ancestors Were in Alaska 3,000 Years Ago

Researchers have discovered that some modern Alaska Natives still live almost exactly where their ancestors did 3,000 years ago, highlighting genetic continuity in Southeast Alaska and shedding light on human migration patterns and pre-colonial territorial patterns in the Pacific Northwest.

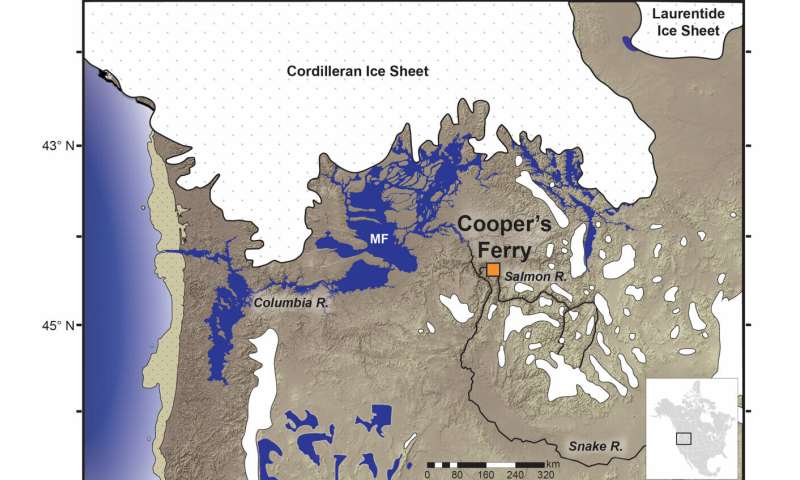

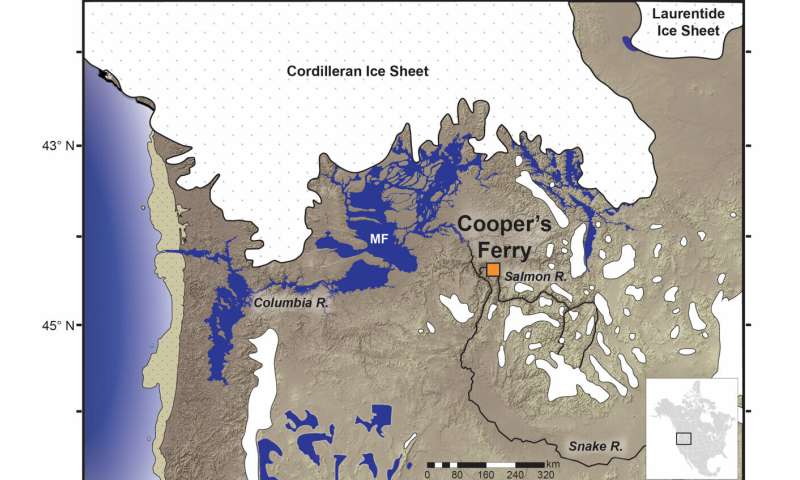

The first people to live in the Americas migrated from Siberia across the Bering land bridge more than 20,000 years ago. Some made their way as far south as Tierra del Fuego, at the tip of South America. Others settled in areas much closer to their place of origin where their descendants still thrive today.

In “A paleogenome from a Holocene individual supports genetic continuity in Southeast Alaska,” published recently in the journal iScience, University at Buffalo evolutionary biologist Charlotte Lindqvist and collaborators show, using ancient genetic data analyses, that some modern Alaska Natives still live almost exactly where their ancestors did some 3,000 years ago.

Lindqvist, PhD, associate professor of biological sciences at the UB College of Arts and Sciences, is senior author of the paper. In the course of her studies in Alaska, she explored mammal remains that had been found in a cave on the state’s southeast coast. One bone was initially identified as coming from a bear. However, genetic analysis showed it to be the remains of a human female.

“We realized that modern Indigenous peoples in Alaska, should they have remained in the region since the earliest migrations, could be related to this prehistoric individual,” says Alber Aqil, a UB PhD student in biological sciences and the first author of the paper. This discovery led to efforts to solve this mystery, which DNA analyses are well suited to address when archeological remains are as sparse as these were.

Learning from an ancestor

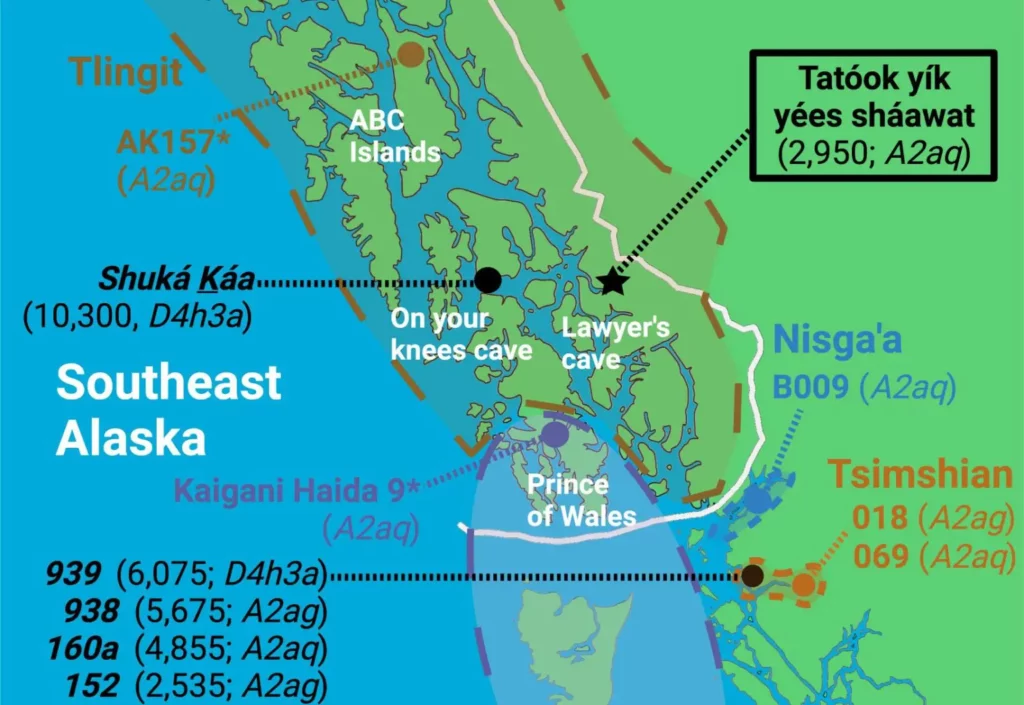

The earliest peoples had already started moving south along the Pacific Northwest Coast before an inland route between ice sheets became viable. Some, including the female individual from the cave, made their home in the area that surrounds the Gulf of Alaska. That area is now home to the Tlingit Nation and three other groups: Haida, Tsimshian, and Nisga’a.

As Aqil and colleagues analyzed the genome from this 3,000-year-old individual — “research that was not possible just 20 years ago,” Lindqvist noted — they determined that she is most closely related to Alaska Natives living in the area today. This fact showed it was necessary to carefully document as clearly as possible any genetic connections of the ancient female to present-day Native Americans.

In such endeavors, it is important to collaborate closely with people living in lands where archeological remains are found. Therefore, cooperation between Alaska Native peoples and the scientific community has been a significant component of the cave explorations that have taken place in the region.

The Wrangell Cooperative Association named the ancient individual analyzed in this study as “Tatóok yík yées sháawat” (Young lady in cave).

Genetic continuity in Southeast Alaska persists for thousands of years

Indeed, Aqil and Lindqvist’s research demonstrated that Tatóok yík yées sháawat is in fact closest related to present-day Tlingit peoples and those of nearby tribes along the coast. Their research, therefore, strengthens the idea that genetic continuity in Southeast Alaska has continued for thousands of years.

Human migration into North America, although it began some 24,000 years ago, came in waves — one of which, about 6,000 years ago — included the Paleo-Inuit, formerly known as Paleo-Eskimos. Importantly for understanding Indigenous peoples’ migrations from Asia, Tatóok yík yées sháawat’s DNA did not reveal ancestry from the second wave of settlers, the Paleo-Inuit. Indeed, the analyses performed by Aqil and Lindqvist helped shed light on the continuing discussion of migration routes, mixtures among people from these different waves, as well as modern territorial patterns of inland and coastal people of the Pacific Northwest in the pre-colonial era.

Oral history links an ancient woman to people living in Southeast Alaska today

The oral origin narratives of the Tlingit people include the story of the most recent eruption of Mount Edgecumbe, which would place them exactly in the region by 4,500 years ago. Tatóok yík yées sháawat, their relative, therefore informs not just modern-day anthropological researchers but also the Tlingit people themselves.

Out of respect for the right of the Tlingit people to control and protect their cultural heritage and their genetic resources, data from the study of Tatóok yík yées sháawat will be available only after review of its use by the Wrangell Cooperative Association Tribal Council.

“It’s very exciting to contribute to our knowledge of the prehistory of Southeast Alaska,” said Aqil.

Reference: “A paleogenome from a Holocene individual supports genetic continuity in Southeast Alaska” by Alber Aqil, Stephanie Gill, Omer Gokcumen, Ripan S. Malhi, Esther Aaltséen Reese, Jane L. Smith, Timothy T. Heaton and Charlotte Lindqvist, 8 April 2023, iScience.