Silver medal featuring winged Medusa discovered at Roman fort near Hadrian’s Wall

A nearly 1,800-year-old silver military medal featuring the snake-covered head of Medusa has been unearthed in what was once the northern edge of the Roman Empire.

Excavators discovered the winged gorgon on June 6 at the English archaeological site of Vindolanda, a Roman auxiliary fort that was built in the late first century, a few decades before Hadrian’s Wall was constructed in A.D. 122 to defend the empire against the Picts and the Scots.

The “special find” is a “silver phalera (military decoration) depicting the head of Medusa,” according to a Facebook post from The Vindolanda Trust, the organization leading the excavations. “The phalera was uncovered from a barrack floor, dating to the Hadrianic period of occupation.”

Medusa — who is known for having snakes for hair and the ability to turn people into stone with a mere glance — is mentioned in multiple Greek myths.

In the most famous story, the Greek hero Perseus beheads Medusa as she sleeps, pulling off the feat by using Athena’s polished shield to indirectly look at the mortal gorgon so that he wouldn’t be petrified, according to the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York City.

Roman culture drew on Greek myths, including Medusa’s story.

During the Roman age, Medusa was seen as apotropaic, meaning her likeness was thought to repel evil, John Pollini, a professor of art history who specializes in Greek and Roman art and archaeology at the University of Southern California, told Live Science. Pollini was not involved in the find at Vindolanda.

“From Greek times on, this is a potent apotropaic to ward off bad things, to keep bad things from happening to you,” Pollini said.

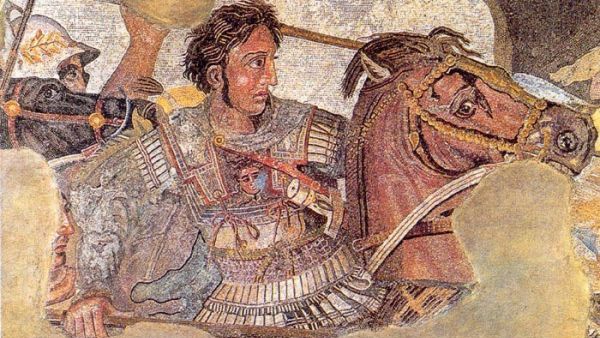

Medusa’s serpent-surrounded head is also seen on Roman-era tombs, mosaics in posh villas, and battle armor. For instance, in the famous first-century mosaic of Alexander the Great from Pompeii, Alexander is depicted with the face of Medusa on his breastplate, Pollini noted.

Medusa is also featured in other Roman-era phalerae, but the details vary. For instance, the Vindolanda Medusa has wings on her head. “Sometimes you see her with wings, sometimes without,” Pollini said. “It probably indicates she has the ability to fly, sort of like [the Roman god] Mercury has little wings on his helmet.”

Because phalerae were awarded for “valor in battle,” military men would attach them to straps and wear them during local parades, Pollini said, noting that the discovery of the Vindolanda phalera is rare.

“There aren’t very many of them, obviously, because they were a precious metal,” he said. “Eventually, most of them were probably melted down.”

Many phalerae are found in burials, but the Vindolanda one appears to be lost. “This isn’t something you would toss away,” Pollini said.

The silver artifact is now undergoing conservation at the Vindolanda lab. It will form part of the 2024 exhibition of finds from the site.