DNA reveals surprise ancestry of mysterious Chinese mummies

Since their discovery a century ago, hundreds of naturally preserved mummies found in China’s Tarim Basin have been a mystery to archaeologists. Some thought the Bronze Age remains were from migrants from thousands of kilometres to the west, who had brought farming practices to the area. But now, a genomic analysis suggests they were indigenous people who may have adopted agricultural methods from neighbouring groups.

As they report today in Nature1, researchers have traced the ancestry of these early Chinese farmers to Stone Age hunter-gatherers who lived in Asia some 9,000 years ago. They seem to have been genetically isolated, but despite this had learnt to raise livestock and grow grains in the same way as other groups.

The study hints at “the really diverse ways in which populations move and don’t move, and how ideas can spread with, but also through, populations”, says co-author Christina Warinner, a molecular archaeologist at Harvard University in Boston, Massachusetts.

The finding demonstrates that cultural exchange doesn’t always go hand in hand with genetic ties, says Michael Frachetti, an archaeologist at Washington University in St. Louis, Missouri. “Just because those people are trading, doesn’t necessarily mean that they are marrying one another or having children,” he says.

Perfect preservation environment

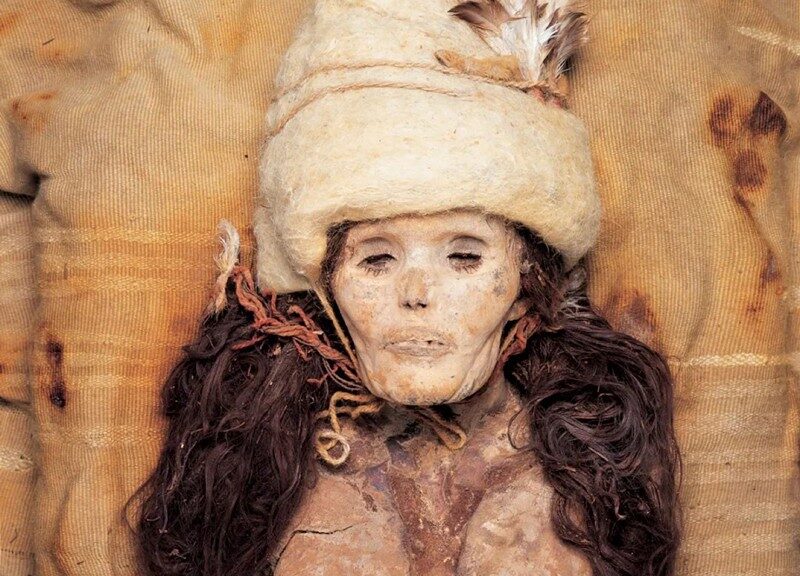

Starting in the early twentieth century, the mummies were found in cemeteries belonging to the so-called Xiaohe culture, which are scattered across the Taklamakan Desert in the Xinjiang region of China.

The desert “is one of the most hostile places on Earth”, says Alison Betts, an archaeologist at the University of Sydney in Australia.

Here, bodies had been buried in boat-shaped coffins wrapped in cattle hide. The hot, arid and salty environment of the desert naturally preserved them, keeping everything from hair to clothing perfectly intact. Before the latest study, “we knew an awful lot about these people, physically, but we knew nothing about who they were and why they were there”, says Betts.

The mummies — which were buried over a period of 2,000 years or more — date to a significant time in Xinjiang’s history, when ancient communities were shifting from hunter-gatherers to farmers, she adds.

Some of the later mummies were buried with woollen fabrics and clothing similar to those of cultures found in the west. The graves also contained millet, wheat, animal bones and dairy products — evidence of agricultural and pastoral technologies characteristic of cultures in other regions of Eurasia, which led researchers to hypothesize that these people were originally migrants from the west, who had passed through Siberia, Afghanistan or Central Asia.

The researchers behind the latest study — based in China, South Korea, Germany and the United States — took DNA from the mummies to test these ideas, but found no evidence to support them.

They sequenced the genomes of 13 individuals who lived between 4,100 and 3,700 years ago and whose bodies were found in the lowest layers of the Tarim Basin cemeteries in southern Xinjiang, as well as another 5 mummies from hundreds of kilometres away in northern Xinjiang, who lived between 5,000 and 4,800 years ago.

They then compared the genetic profiles of these people with previously sequenced genomes from more than 100 ancient groups of people, and those of more than 200 modern populations, from around the world.

Two groups of people

They found that the northern Xinjiang individuals shared some parts of their genomes with Bronze Age migrants from the Altai Mountains of Central Asia who lived about 5,000 years ago — supporting an earlier hypothesis.

But the 13 people from the Tarim Basin did not share this ancestry. They seem to be solely related to hunter-gatherers who lived in southern Siberia and what is now northern Kazakhstan some 9,000 years ago, says co-author Choongwon Jeong, a population and evolutionary geneticist at Seoul National University. The northern Xinjiang individuals also shared some of this ancestry.

Evidence of dairy products was found alongside the youngest mummies from the upper layers of cemeteries in the Tarim Basin, so the researchers analysed calcified dental plaque on the teeth of some of the older mummies to see how far back dairy farming went. In the plaque, they found milk proteins from cattle, sheep and goats, suggesting that even the earliest settlers here consumed dairy products. “This founding population had already incorporated dairy pastoralism into their way of life,” says Warinner.

But the study raises many more questions about how the people of the Xiaohe culture got these technologies, from where and from whom, says Betts. “That’s the next thing we need to try and resolve.”