Mexico earthquake reveals lost ancient temple inside the pyramid

The remains of the great pyramid of Teopanzolco have long offered visitors to the southern Mexican site unique insights into the structure’s inner workings while simultaneously conjuring visions of the intricate temples that once arose from its series of bases and platforms.

Today, remnants of twin temples—to the north, a blue one dedicated to the Aztec rain god Tláloc, and to the south, a red one dedicated to the Aztec sun god Huitzilopochtli—still top the pyramid’s central platform, joined by parallel staircases.

Although archaeologists have intermittently excavated the Teopanzolco site since 1921, it took a deadly 7.1 magnitude earthquake to unveil one of the pyramid’s oldest secrets: an ancient shrine buried about six-and-a-half feet below Tláloc’s main temple.

According to BBC News, scientists from Mexico’s National Institute of Anthropology and History (INAH) discovered the temple while scanning the pyramid for structural issues.

The earthquake, which struck central Mexico on September 19, 2017, caused “considerable rearrangement of the core of [the pyramid’s] structure,” INAH archaeologist Bárbara Konieczna said in a statement.

For local news outlet El Sol de Cuernavaca, Susana Paredes reports that some of the most serious damage occurred in the upper part of the pyramid, where the twin temples are located; the floors of both structures had sunk and bent, leaving them dangerously destabilized.

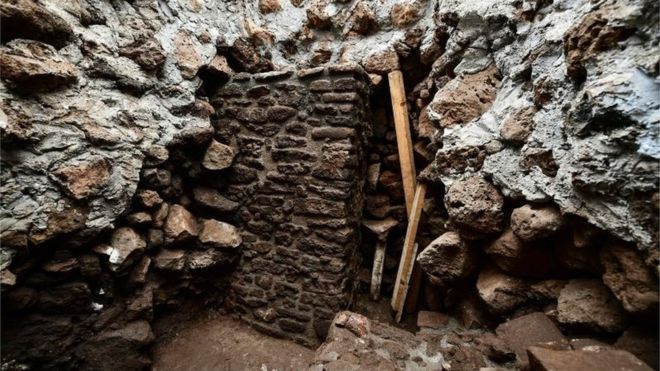

To begin recovery efforts, archaeologists created wells in the temple dedicated to Tláloc and a corridor separating the two temples.

During this work, the team unearthed a previously unknown structure, which featured a similar architectural style—double facade walls covered in elongated stones and stucco-encased slabs—to that of the existing Tláloc temple.

In the statement, Konieczna notes that the temple would have measured about 20 feet by 13 feet and was probably dedicated to Tláloc, just like the one located above it. It’s possible that a matching temple dedicated to Huitzilopochtli lies on the opposite side of the newly located one, buried by later civilizations’ architectural projects.

The humidity of the Morelos region had damaged the temple’s stucco walls, according to a press release, but archaeologists were able to save some of the remaining fragments.

Below the shrine’s stuccoed floors, they found a base of tezontle, a reddish volcanic rock widely used in Mexican construction, and a thin layer of charcoal. Within the structure, archaeologists also discovered shards of ceramic and an incense burner.

Paredes of El Sol de Cuernavaca notes that the temple likely dates to about 1150 to 1200 C.E. Comparatively, the main structure of the pyramid dates to between 1200 and 1521, indicating that later populations built over the older structures.

The Teopanzolco site originated with the Tlahuica civilization, which founded the city of Cuauhnahuac (today is known as Cuernavaca) around 1200, as G. William Hood chronicles for Viva Cuernavaca. During the 15th century, the Tlahuica people were conquered by the Aztecs, who, in turn, took over the construction of the Teopanzolco pyramids.

Following the 16th-century arrival of the Spanish conquistadors, the project was abandoned, leaving the site untouched until its 1910 rediscovery by Emiliano Zapata’s revolutionary forces.