Lasers reveal ruins of the 5th-century fortress in the Spanish forest

Archaeologists in Spain got the surprise of a lifetime when they discovered the ruins of a powerful fifth-century fortress surrounded by a huge defensive wall in a dense forest, instead of the Iron Age fort they had been looking for, they reported in a new study.

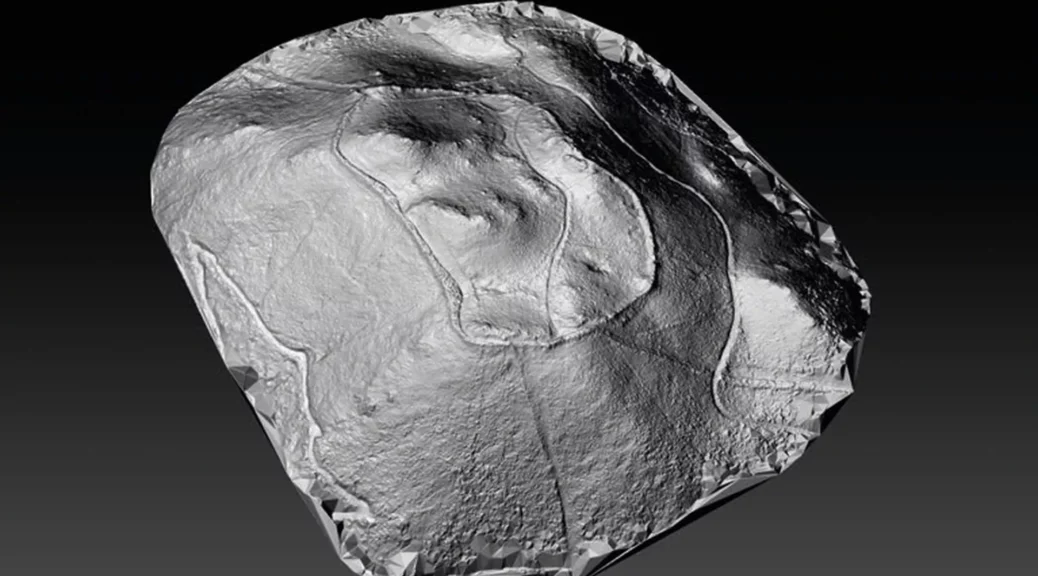

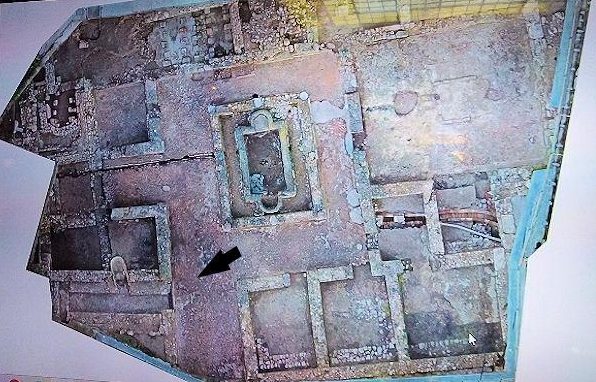

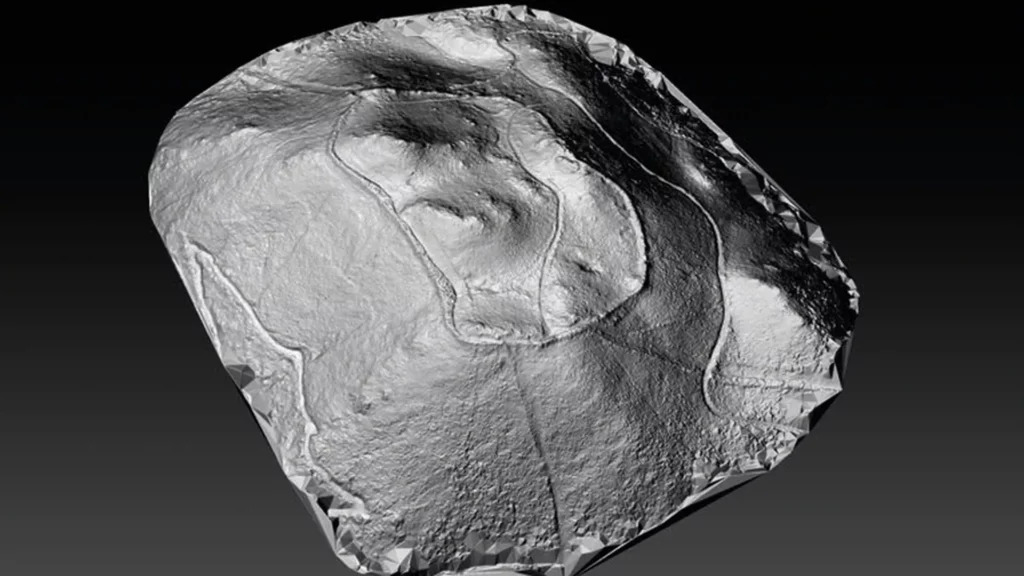

The team found the stronghold on a hilltop in northwestern Spain by using lidar — light detection and ranging — to peer beneath a forest covering the ruins. This technique, which bounces hundreds of thousands of laser pulses every second off the landscape from an aircraft flying overhead, revealed an early medieval fortress covering about 25 acres (10 hectares), with 30 towers and a defensive wall about three-quarters of a mile (1.2 kilometers) long.

The fortress seems to have been built in the first half of the fifth century A.D., possibly on top of an earlier Iron Age hilltop fort, to defend against Germanic invaders after Roman control of the region had collapsed, study author Mário Fernández-Pereiro, an archaeologist at University College London and the University of Santiago de Compostela (USC), told Live Science.

The site, called Castro Valente (“Brave Fort”), is in the Galicia region’s Padrón district, about 16 miles (16 km) southwest of the city of Santiago de Compostela.

Hilltop fortress

Locals thought Castro Valente had been built after the about ninth century B.C. by a Celtic people, called the “Callaeci” in Latin, who lived in Galicia at that time.

Another Celtic tribe, called the Astures, lived to the east in what’s now the Spanish region of Asturias, while others, called the Lusitani, lived to the south in what’s now Portugal.

Until they were subsumed by the expanding Roman Empire in the first century B.C., the Callaeci and the Astures formed the “Castro culture” of fortified hilltop settlements — and modern-day Galicia is filled with their ruins, according to the December 2022 study, published in Cuadernos de Arqueología de la Universidad de Navarra (Archaeological Journal of the University of Navarra).

When Fernández-Pereiro and José Carlos Sánchez-Pardo, also a USC archaeologist and co-author of the study, began researching the site, they also thought Castro Valente was a fortified Celtic settlement. But they soon found evidence that the buried structure was much larger than they expected and that parts of it were built with methods not used in the Iron Age.

The archaeological excavations “continued to provide data that point us towards a time of post-Roman occupation, presumably in the first half of the 5th century,” Fernánandez-Pereiro said in an email.

Germanic invaders

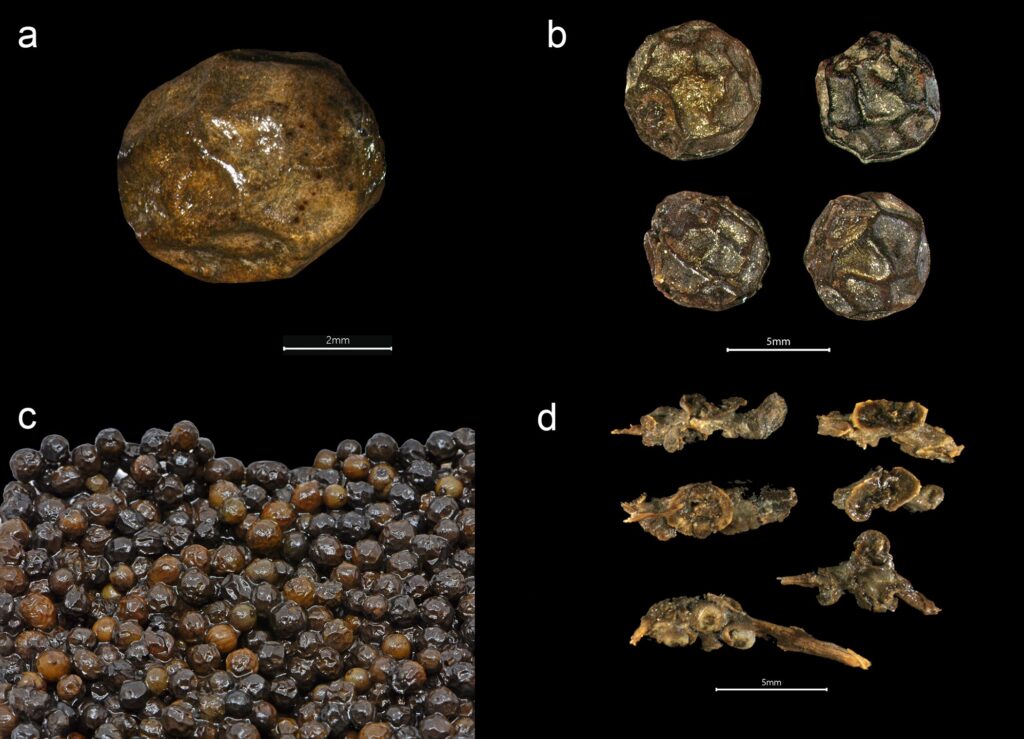

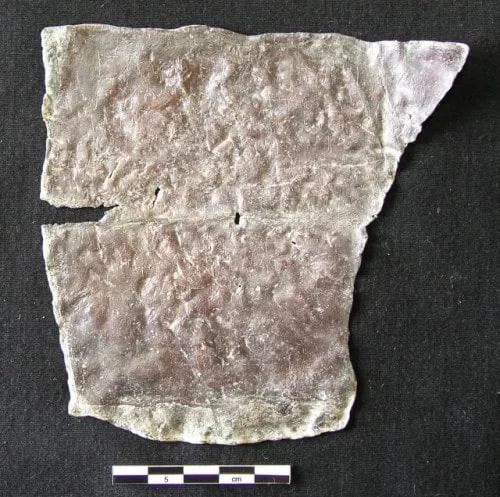

The fortress’s layout, construction and fragments of pottery found there suggest it was built after the Roman Empire lost control of the region in about the early fifth century A.D., when Spain was overrun by Germanic invaders. Galicia fell to the Suevi people (also spelled Suebi), who originated in the Elbe River region of what’s now Germany and the Czech Republic, and the fortress seems to have been built by local people for their defense at that time, Fernández-Pereiro said.

“We understand that the local powers of Galicia needed a tool to reaffirm and control the territory in the midst of this transition from Antiquity to the Early Middle Ages,” he said.

But the fortress seems to have been abandoned roughly 200 years later, possibly because it was no longer needed, Fernández-Pereiro said. Future research may reveal more about it, as well as protect it from development, such as forest roads and wind farms. The team plans to regularly update their Facebook page, CastelosnoAire, as research progresses.

Ken Dark, an archaeologist at King’s College London who wasn’t involved in the study, told Live Science that the fifth-century Castro Valente site seemed to be based on the reuse of a Celtic fort — something that was also seen in Britain after the collapse of Roman rule.

In the fifth and sixth centuries A.D., many Britons from what are now Wales and Cornwall fled the Anglo-Saxon invasion by immigrating to Galicia, alongside the more famous migration of Britons to what’s now known as Brittany in western France, he said.

“It is fascinating to find a site like this in a region strongly associated with Britain during Late Antiquity,” Dark said.

CREDIT TO: livescience.com