1 billion-year-old fossil ‘balls’ may be Earth’s earliest known multicellular life

Scientists have discovered a rare evolutionary “missing link” dating to the earliest chapter of life on Earth. It’s a microscopic, ball-shaped fossil that bridges the gap between the very first living creatures — single-celled organisms — and more complex multicellular life.

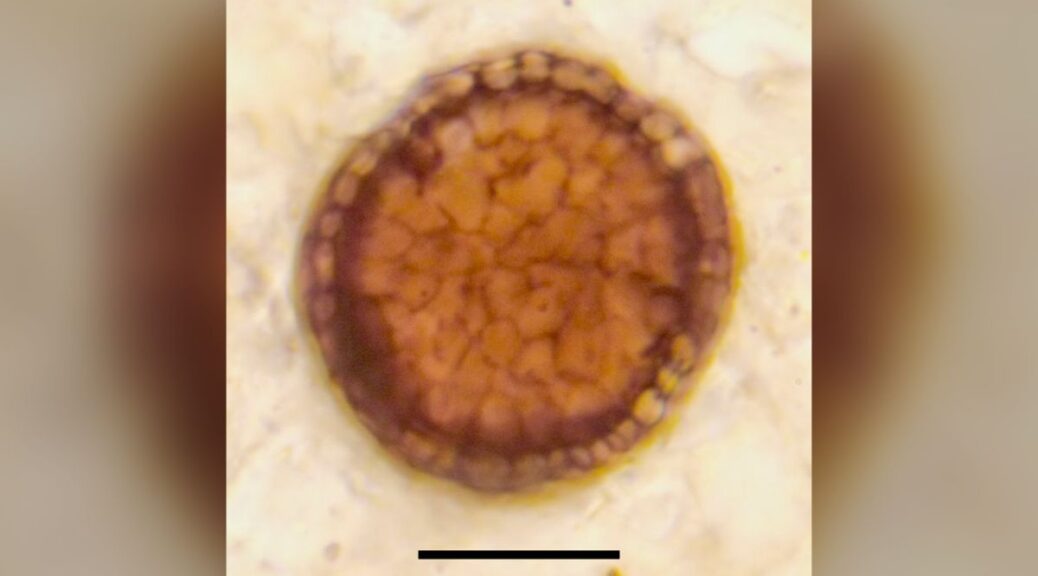

The spherical fossil contains two different types of cells: round, tightly packed cells with very thin cell walls at the centre of the ball, and a surrounding outer layer of sausage-shaped cells with thicker walls. Estimated to be 1 billion years old, this is the oldest known fossil of a multicellular organism, researchers reported in a new study.

Life on Earth is widely accepted as having evolved from single-celled forms that emerged in the primordial oceans. However, this fossil was found in sediments from the bottom of what was once a lake in the northwest Scottish Highlands. The discovery offers a new perspective on the evolutionary pathways that shaped multicellular life, the scientists said in the study.

“The origins of complex multicellularity and the origin of animals are considered two of the most important events in the history of life on Earth,” said lead study author Charles Wellman, a professor in the Department of Animal and Plant Sciences at the University of Sheffield in the United Kingdom.

“Our discovery sheds new light on both of these,” Sheffield said in a statement.

Today, little evidence remains of Earth’s earliest organisms. Microscopic fossils estimated to be 3.5 billion years old are credited with being the oldest fossils of life on Earth, though some experts have questioned whether chemical clues in the so-called fossils were truly biological in origin.

Other types of fossils associated with ancient microbes are even older: Sediment ripples in Greenland date to 3.7 billion years ago, and hematite tubes in Canada date between 3.77 billion and 4.29 billion years ago. Fossils of the oldest known algae, ancestor to all of Earth’s plants, are about 1 billion years old, and the oldest sign of animal life — chemical traces linked to ancient sponges — are at least 635 million and possible as much as 660 million years old, Live Science previously reported.

The tiny fossilized cell clumps, which the scientists named Bicellum brasieri, were exceptionally well-preserved in 3D, locked in nodules of phosphate minerals that were “like little black lenses in rock strata, about one centimetre [0.4 inches] in thickness,” said lead study author Paul Strother, a research professor in the Department of Earth and Environmental Sciences at Boston College’s Weston Observatory.

“We take those and slice them with a diamond saw and make thin sections out of them,” grinding the slices thin enough for light to shine through — so that the 3D fossils could then be studied under a microscope, Strother told Live Science.

The researchers found not just one B. brasieri cell clump embedded in phosphate, but multiple examples of spherical clumps that showed the same dual cell structure and organization at different stages of development. This enabled the scientists to confirm that their find was once a living organism, Strother said.

“Bicellum” means “two-celled,” and “brasieri” honours the late palaeontologist and study co-author, Martin Brasier. Prior to his death in 2014 in a car accident, Brasier was a professor of paleobiology at the University of Oxford in the U.K., Strother said.

Multicellular and mysterious

In the B. brasieri fossils, which measured about 0.001 inches (0.03 millimeters) in diameter, the scientists saw something they had never seen before: evidence from the fossil record marking the transition from single-celled life to multicellular organisms. The two types of cells in B. brasieri differed from each other not only in their shape, but in how and where they were organized in the organism’s “body.”

“That’s something that doesn’t exist in normal unicellular organisms,” Strother told Live Science. “That amount of structural complexity is something that we normally associate with complex multicellularity,” such as in animals, he said.

According to the study it’s unknown what type of multicellular lineage B. brasieri represents, but its round cells lacked rigid walls, so it probably wasn’t a type of algae. In fact, the shape and organization of its cells “are more consistent with a holozoan origin,” the authors wrote. (Holozoa is a group that includes multicellular animals and single-celled organisms that are animals’ closest relatives).

The Scottish Highlands site — formerly an ancient lake — where the scientists found B. brasieri presented another intriguing puzzle piece about early evolution.

Earth’s oldest forms of life are typically thought to have emerged from the ocean because most ancient fossils were preserved in marine sediments, Strother explained. “There aren’t that many lake deposits of this antiquity, so there’s a bias in the rock record toward a marine fossil record rather than a freshwater record,” he added.

B. brasieri is therefore an important clue that ancient lake ecosystems could have been as important as the oceans for the early evolution of life.

Oceans provide organisms with a relatively stable environment, while freshwater ecosystems are more prone to extreme changes in temperature and alkalinity — such variations could have spurred an evolution in freshwater lakes when more complex life on Earth was in its infancy, Strother said.