People ‘finger painted’ the skulls of their ancestors red in the Andes a millennium ago

Up to a millennium ago, the Chincha people in what is now Peru decorated their ancestors’ remains with red pigment, sometimes finger-painting their skulls as part of a ritual intended to give the dead a new kind of social life.

In a new investigation, researchers analyzed hundreds of human remains found in the Chincha Valley of southern Peru. Dating to between A.D. 1000 and 1825, the skeletal remains they studied were found in more than 100 “chullpas,” large mortuary structures where multiple people were interred together. The team’s goal, detailed in the March 2023 issue of the Journal of Anthropological Archaeology, was to investigate how and why red paint was applied to many of the bones.

What they discovered, however, was that different kinds of red paint were used and that only certain people were painted after death.

The use of red pigment in funeral rituals dates back thousands of years in Peru and is related to a prolonged process of dealing with deceased members of society. “Death was not the end,” the researchers wrote in the study. “It was a pivotal moment of transformation into another kind of existence, and a critical transition from one state to another, providing the basis for further life.”

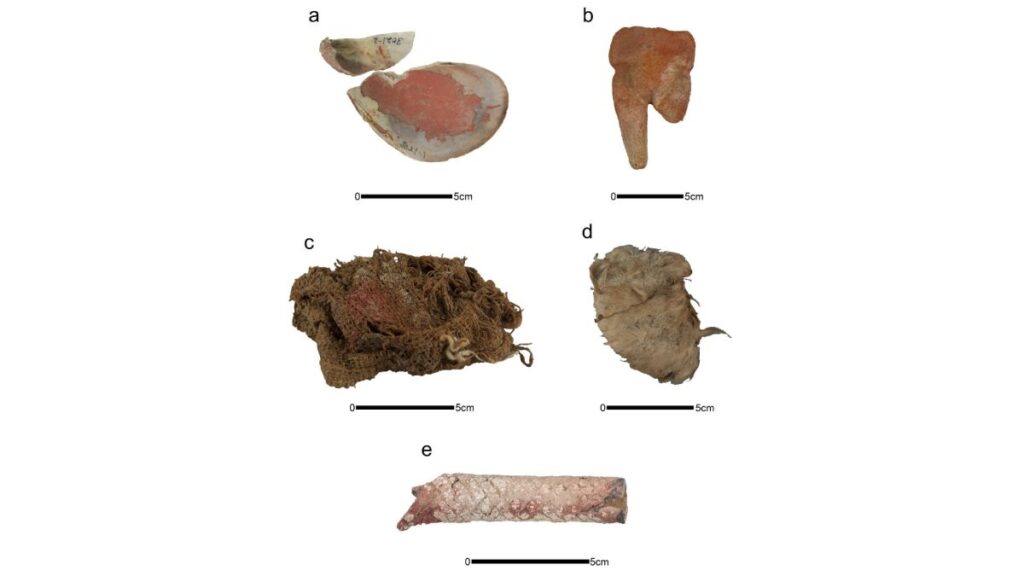

The researchers took samples of red paint from 38 different artifacts and bones, 25 of which were human skulls. Using three scientific techniques — X-ray powder diffraction, X-ray fluorescence spectrometry, and laser ablation ICP-MS, techniques that essentially analyze elements within a substance — they identified the composition of the red pigments.

Red paint on 24 of the samples came from iron-based ochres like hematite, 13 came from mercury-based cinnabar, and one was a combination of the two.

Further chemical analysis showed that the cinnabar was imported from hundreds of miles away while the hematite likely came from local sources. These differences may reflect elite and non-elite uses of the different kinds of paint, the study authors said.

Most of the individuals whose bones were painted were found to be adult males. However, the bones of women and children, as well as those of several people with healed traumatic injuries and people whose skulls were modified as babies, were also painted.

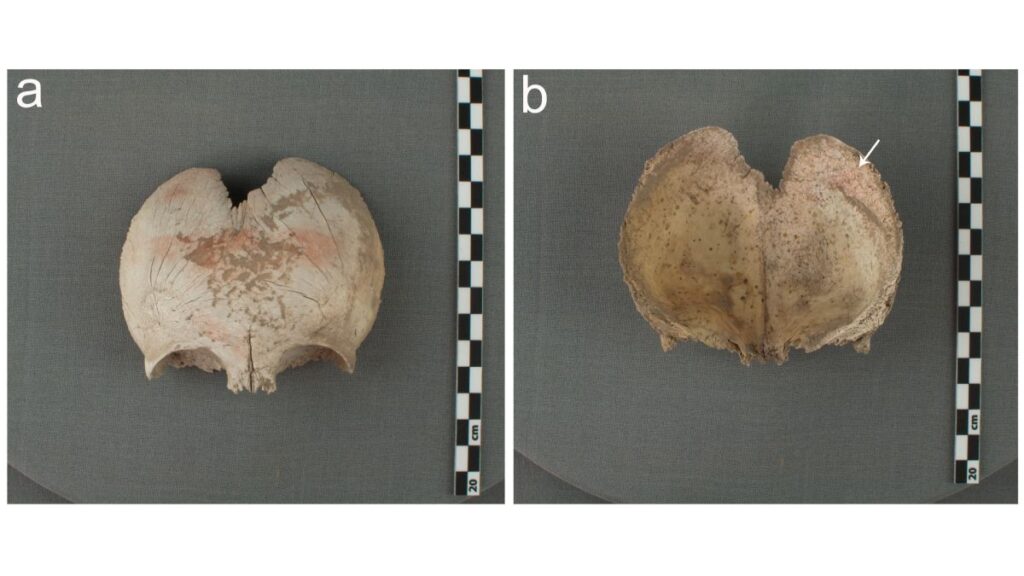

By examining the skulls, the researchers figured out how the red paint was applied. “We know that Chincha peoples used textiles, leaves, and their own hands to apply red pigment to human remains,” study first author Jacob Bongers, an anthropological archaeologist at Boston University, told Live Science in an email. Thick vertical or horizontal lines of paint on skulls are consistent with someone using their fingers for application.

“Finger painting would have been critical for forming close relationships between the living and the dead,” Bongers said. “The red pigment itself brings to light this living-dead relationship as well as social differences for others to see.”

Benjamin Schaefer, a bioarchaeologist at the University of Illinois Chicago who was not involved in the study, told Live Science in an email that this research “makes an important and exciting contribution to understanding the ritual economy of death in the Andes. The living hand-painting the dead after death offers an intimate and dynamic glimpse into social identities in the Chincha Valley.”

One aspect of the process that Bongers and colleagues have not figured out yet is when the red paint was applied. While it is clear to them that the bones were painted after the individuals had been skeletonized, the actual act of painting might have been a response to colonization.

“Some painted bones, especially crania [skulls], were removed and placed over other graves, presumably to ‘protect’ the dead,” the researchers wrote. By integrating theories rooted in Andean concepts of death and cosmology with the scientific analysis of painted skeletons, they further suggest that transgressions against the dead, such as looting, would have required correction by the living. “We hypothesize that individuals reentered disturbed chullpas to paint human remains that had become desecrated after the European invasion,” the researchers wrote.

“Their research provides a roadmap for others to follow,” Celeste Gagnon, a bioarchaeologist at Wagner College in New York who was not involved in the study, told Live Science in an email, “to create work that fulfills a unique promise of anthropology: bringing together humanistic and scientific understandings of the past.”