World’s oldest sperm found in Queensland cave

Scientists have discovered the world’s oldest and best-preserved sperm from tiny shrimps, measuring a massive 1.3 millimetres and dating back to 17 million years in Australia.

Preserved giant sperm from shrimps were found at the Riversleigh World Heritage Fossil Site in Queensland and are the oldest fossilised sperm ever found in the geological record, researchers said.

The shrimps lived in a pool in an ancient cave inhabited by thousands of bats, and the presence of bat droppings in the water could help explain the almost perfect preservation of the fossil crustaceans.

The giant sperm are thought to have been longer than the male’s entire body but are tightly coiled up inside the sexual organs of the fossilised freshwater crustaceans, which are known as ostracods.

“These are the oldest fossilised sperm ever found in the geological record,” said Professor Mike Archer, from the University of New South Wales (UNSW), who has been excavating at Riversleigh for more than 35 years.

“The discovery of fossil sperm, complete with sperm nuclei, was totally unexpected,” said Archer.

A UNSW research team led by Archer, Associate Professor Suzanne Hand and Henk Godthelp collected the fossil ostracods from the Bitesantennary Site at Riversleigh in 1988.

They were sent to John Neil, a specialist ostracod researcher at La Trobe University, who realised they contained fossilised soft tissues.

He drew this to the attention of European specialists, including the lead author of the research paper, Dr Renate Matzke-Karasz, from the Ludwig Maximilian University of Munich, who examined the specimens with Dr Paul Tafforeau at the European Synchrotron Radiation Facility in Grenoble, France.

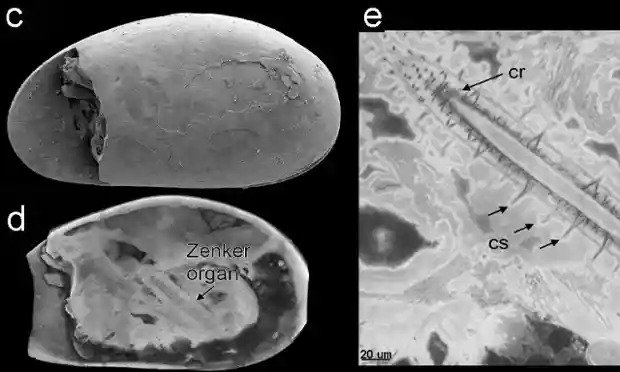

The microscopic study revealed the fossils contain the preserved internal organs of the ostracods, including their sexual organs.

Within these are the almost perfectly preserved giant sperm cells, and within them, are the nuclei that once contained the animals’ chromosomes and DNA.

Also preserved are the Zenker organs – chitinous-muscular pumps used to transfer the giant sperm to the female. The researchers estimate the fossil sperm is about 1.3 millimetres long, about the same length or slightly longer than the ostracod itself.

“About 17 million years ago, Bitesantennary Site was a cave in the middle of a vast biologically diverse rainforest. Tiny ostracods thrived in a pool of water in the cave that was continually enriched by the droppings of thousands of bats,” said Archer.

The bats could have played a role in the extraordinary preservation of the ostracod sperm cells, UNSW’s Associate Professor Suzanne Hand said.

The steady rain of poo from thousands of bats in the cave would have led to high levels of phosphorus in the water, which could have aided the mineralisation of the soft tissues.

The study was published in the journal Proceedings of the Royal Society B