10-Foot-Tall Stone Jars ‘Made by Giants’ Stored Human Bodies in Ancient Laos

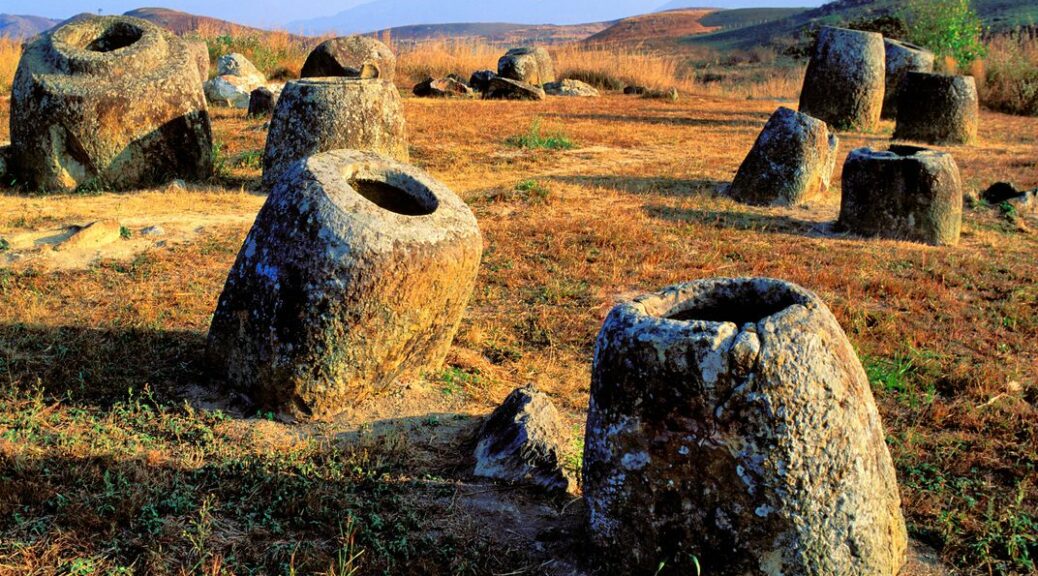

Stonehenge inspires awe, but there’s an even more mysterious ancient scene in Laos. The Plain of Jars consists of thousands of prehistoric stone vessels scattered over hundreds of square kilometres near Phonsavan, in the northeastern part of the country—a hilly area, despite the “plain” in the name. The huge jars form a surreal sight—some are up to ten feet tall and weigh several tons. It’s an archaeological wonder that experts still haven’t pinned down.

Several human burials, thought to be around 2,500 years old, have been found at some of these sites in Laos, but nothing is known about the people who originally made the jars.

An expedition of archaeologists from Laos and Australia visited the Xiangkhouang region in February and March this year to document known jar sites and to search for new jars-of-the-dead sites and stone quarries.

The new finds show that the mysterious culture that made the stone jars were geographically more widespread than previously thought, said Louise Shewan, an archaeologist at the University of Melbourne, and one of the expedition leaders.

The largest and best-known jar site is the famous Plain of Jars, located in relatively open country near the town of Phonsavan. That site contains around 400 carved stone jars, some as tall as 10 feet (3 m) and weighing more than 10 tons (9,000 kilograms), and the first archaeological investigation of it was made in the 1930s.

But Shewan said that the majority of the jar sites usually contained fewer than 60 carved stone jars, and were found in forested and mountainous terrain surrounding the Plain of Jars, spread over thousands of square miles.

Ancient stone jars

Shewan told Live Science that the search for new jar sites took the expedition into “extremely rugged, forested terrain,” as the researchers looked for ancient relics reported by local people.

Relying on local knowledge meant the archaeologists could avoid the ever-present danger of unexploded Vietnam War-era bombs, she said. U.S. warplanes dropped an estimated 270 million cluster bombs on Laos during the war.

The Laos government agency that oversees clearance efforts reports that more than 80 million unexploded bombs are scattered around the country.

The latest expedition, in addition to accurately mapping many of the reported sites in the Xiangkhouang region, found 15 new jar sites, containing a total of 137 ancient stone jars.

Shewan said that the newly discovered jars were similar to those found on the Plain of Jars, but some varied in the types of stone that they were made from, their shapes and the way the rims of the jars were formed.

Burial rituals

Local legends include a story that the enormous stone jars were made by giants, who used the vessels to brew rice beer to celebrate a victory in war. But archaeologists think that at least some of the carved stone jars were used to hold dead bodies for a time before their bones would be cleaned and buried.

Although the remains of elaborate human burials have been found at some of the jar sites, archaeologists aren’t sure if the jars were made for the purpose of the burials or if the burials were performed later.

Excavations in 2016 revealed that some of the stone jars were surrounded by pits filled with human bones and by graves covered by large carved disks of stone. These appear to have been used to mark the grave locations.

The latest expedition also found buried disks and other artefacts. Those included several beautifully carved stone disks, decorated on one side with concentric circles, human figures and animals. Curiously, the stone discs were always buried with the carved side face down.

“Decorative carving is relatively rare at the jar sites, and we don’t know why some disks have animal imagery and others have geometric designs,” expedition co-leader Dougald O’Reilly, an archaeologist at Australian National University in Canberra, said in a statement.

The excavations around some of the stone jars also revealed decorative ceramics, glass beads, iron tools, decorative disks that were worn in the ears and spindle whorls for cloth making. Researchers also discovered several miniature clay jars that looked just like the giant stone jars and that were buried with the dead.

The scientists will now use the data and photographs from the new jar finds to reconstruct the sites in virtual reality at Monash University; then, archaeologists across the globe can use the VR to examine the sites in detail.