86,000-year-old human bone found in Laos cave hints at ‘failed population’ from prehistory

Homo sapiens arrived in Southeast Asia as early as 86,000 years ago, a human shin bone fragment found deep within a cave in Laos reveals.

The finding comes from the cave of Tam Pà Ling, or Cave of the Monkeys, which sits at around 3,840 feet (1,170 meters) above sea level on a mountain in northern Laos. Human bone fragments previously found in the cave were 70,000 years old, making them some of the earliest evidence of humans in this area of the world. This discovery prompted archaeologists to dig deeper.

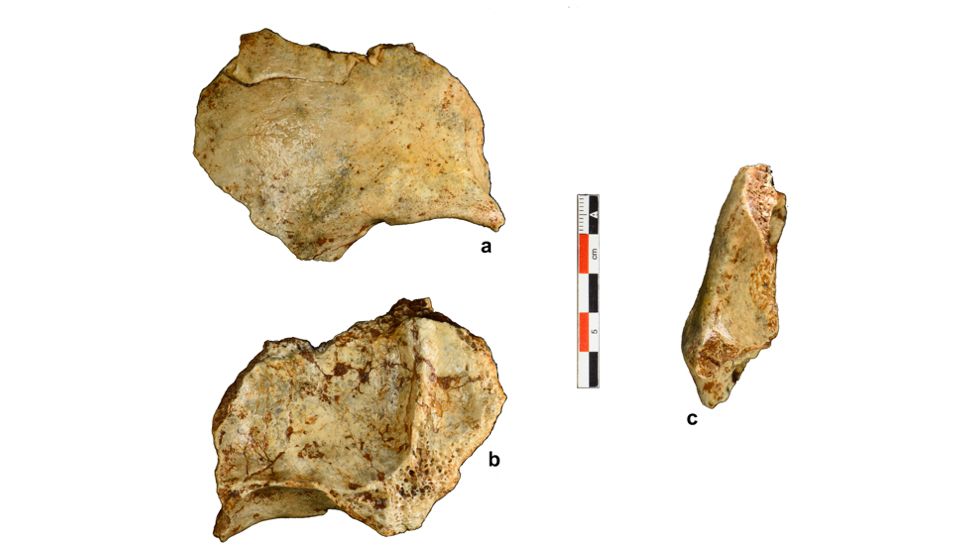

The team did just that, finding two new bones, they reported in a study published Tuesday (June 13) in the journal Nature Communications. The bones — fragments of the front of a skull and a shin bone — were likely washed into the Tam Pà Ling cave during a monsoon.

Even though the bones were fractured and incomplete, the researchers were able to compare their dimensions and shape with other bones from early humans, finding that they most closely matched Homo sapiens rather than other archaic humans, such as Homo erectus, Neandertals or Denisovans.

The researchers used luminescence dating of nearby sediments and uranium-series dating of mammalian teeth from the same layers to produce an age range for the human remains. Luminescence dating is a technique that measures the last time crystalline materials, such as stones, were exposed to sunlight or heat, while U-series dating is a radiometric technique that, similar to carbon-14 dating, measures the decay of uranium over time into thorium, radium and lead.

The skull, they estimated, was up to 73,000 years old, and the shin bone dates back as far as 86,000 years ago.

This early date is a remarkable finding, particularly because researchers have long debated the timing of Homo sapiens’ arrival in Asia.

“Little to no anthropological research was done in Laos since the second world war,” study lead author Fabrice Demeter, a paleoanthropologist at the University of Copenhagen, told Live Science in an email.

Debates about human colonization of Southeast Asia have taken place for decades as researchers have attempted to understand how and when humans crossed straits and seas to eventually end up in Australia.

Tam Pà Ling is therefore “a prime place to ask some of these questions about migration, since mainland southeast Asia really sits at the crossroads of East Asia and island SE Asia/Australia.”

While the genetic and stone tool evidence amassed to date strongly supports a single, rapid dispersal of Homo sapiens from Africa sometime after 60,000 years ago, studies such as this one are producing evidence for earlier migrations, many of which may have been dead ends.

Michael B.C. Rivera, a biological anthropologist at the University of Hong Kong who was not involved in the study, told Live Science in an email that “perhaps this was a group that dispersed to Southeast Asia and died out before they were able to contribute genes to today’s human gene pool. I find the narratives of these ‘failed’ populations interesting to add so that we aren’t just looking at the ‘successful’ ones that ‘made it’.”

No stone tools or other clues about these humans’ lifestyles have been found in Tam Pà Ling. But archaeologists working on the prehistory of Asia have long suspected that, even before 65,000 years ago, ancient humans were capable of reaching islands and making sea crossings to populate seemingly remote parts of the world, Rivera pointed out.

“The claim that H. sapiens made it to this region pre-60,000 years ago is not new,” Rivera said, “but it is good to have further confirmation in our attempts to fill in gaps in the archaeological record.”