A broken pagan statue of the Greek god Pan was unearthed at early church ruins in Istanbul

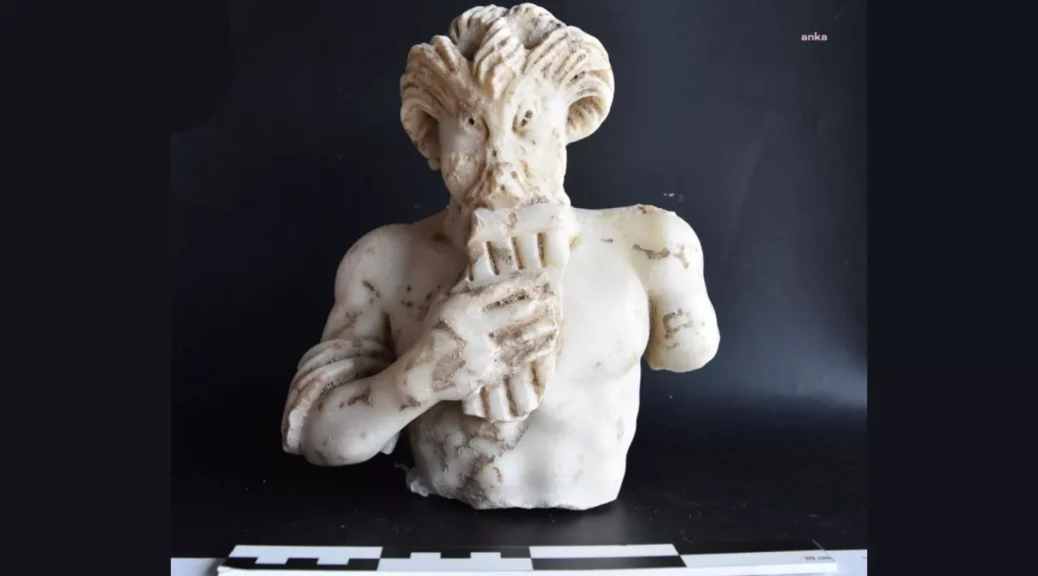

Archaeologists in Istanbul excavating the ruins of an early Christian church have unearthed a pagan statue of the Greek god Pan, who is depicted with goat horns and a naked torso as he plays a reed pipe.

It is unlikely that a Christian church would have kept a statue of such a pagan god. Rather, archaeologists think the statue’s location is the result of a modern mistake.

The ruins are from the sixth-century church of St. Polyeuctus, which was one of the largest in Constantinople — as Istanbul was called before its conquest by Ottoman Turks in 1453.

In the 1960s, workers building a nearby road discovered the remains of the church by accident. After an excavation, archaeologists used backfill — earth used to fill holes and level ground — to cover up the ruins. It’s likely that the statue was part of that backfill, Mahir Polat, the deputy general secretary of the Istanbul Metropolitan Municipality (IBB) told Live Science in an email.

The new discovery comes only a few weeks after buried rooms and a tunnel were reopened beneath the St. Polyeuctus ruins, as the IBB redevelops the formerly derelict area into an archaeological tourist attraction.

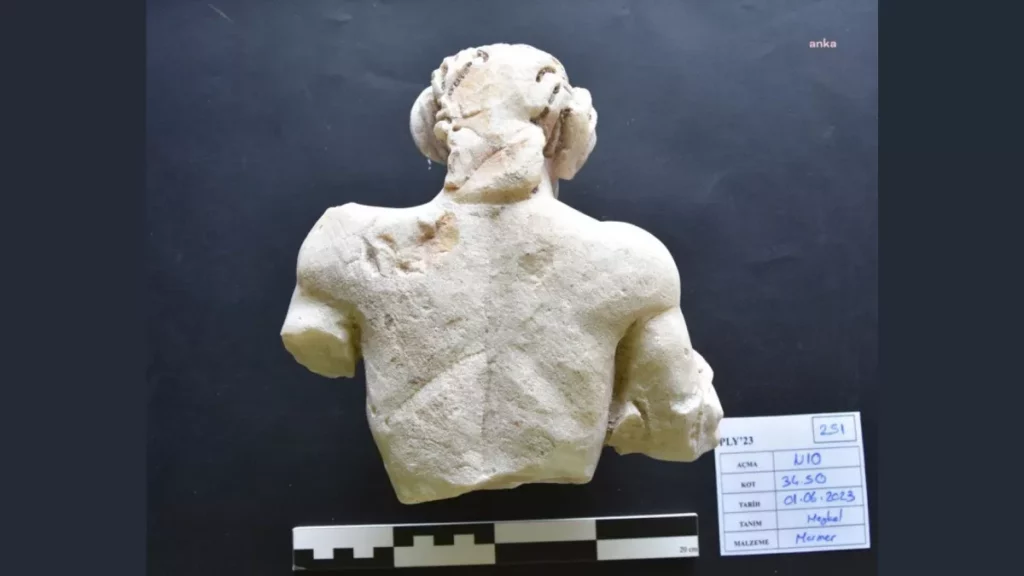

Polat said the statue was found on June 1 on the northwest side of the main church building, in backfill about 8.5 feet (2.6 meters) below the surface. The marble statue is less than a foot (20 centimeters) tall and is badly damaged: only its head, torso, and arm remain. But its significance as a work of Classical art is still visible.

The statue appears to have been made during the Roman period, Polat said before Constantinople was founded in A.D. 330; further examinations might date it more precisely.

Wild Greek god

Pan was the mythical ancient Greek god of the wilds, woods, fields, shepherds, and flocks, according to the American classicist Timothy Gantz in “Early Greek Myth: A Guide to Literary and Artistic Sources” (Johns Hopkins University Press, 1996). He originally may have been a fertility deity, and his reputation included cavorting with nymphs, who were female nature deities bound to trees, streams, and other features of the landscape.

Pan famously played a set of reed pipes — now called Pan pipes in his honor — and was typically portrayed as a mythical faun, with the cloven hooves, furry hind legs, and horns of a goat. (The devil in Christianity is often portrayed in the same way, and the British historian Ronald Hutton argues that isn’t an accident.)

According to the Online Etymological Dictionary, the modern English word “panic” is derived from the god’s name, from the Greek word “panikon,” which means “pertaining to Pan.” Supposedly, Pan was responsible for making mysterious woodland sounds that “caused groundless fear in herds and crowds, or in people in lonely spots.”

Archaeologist and historian Ken Dark of King’s College London, an expert on ancient Istanbul who wasn’t involved in the discovery, told Live Science the Pan statue was probably among the many Classical objects brought to Constantinople between the fourth and sixth centuries A.D. “as works of art or for their historical interest.”

“None were displayed in churches or monasteries, but instead were used as ornaments in secular public places and aristocratic palaces,” he said in an email. “This statue was presumably deposited, broken, in the ruins of the church after the building had gone out of use.”

It isn’t known why Constantinople stopped importing such figures after the sixth century. Perhaps these artworks were increasingly seen as unchristian as the Byzantine aristocracy focused less on Classical culture and more on Christian culture, Dark said.