Ancient Egyptian attempts to treat cancer seen in nearly 5,000-year-old skull

Archaeologists have unearthed evidence of ancient practices which might change our understanding of ancient Egyptian life.

Two skulls, both thousands of years old, bear cut marks which could be indications of attempted operations to treat cancer, or perhaps even to conduct postmortems to learn more about excessive tissue growth.

It is known that as an early civilisation, the ancient Egyptians were skilled in medical practices. Historical records note that they could identify, describe and treat diseases and traumatic injuries. They even build prostheses and inserted dental fillings.

The new study, published in Frontiers in Medicine, suggests they may have even tried to treat cancers.

Two skulls were examined as part of the research.

Skull and mandible 236 belonged to a male who died at age 30–35. The bones were found at Giza and are dated to between 2687 and 2345 BCE, during Egypt’s Old Kingdom – around the time that the Pharaoh Khufu ordered the building of the largest of the pyramids of Giza.

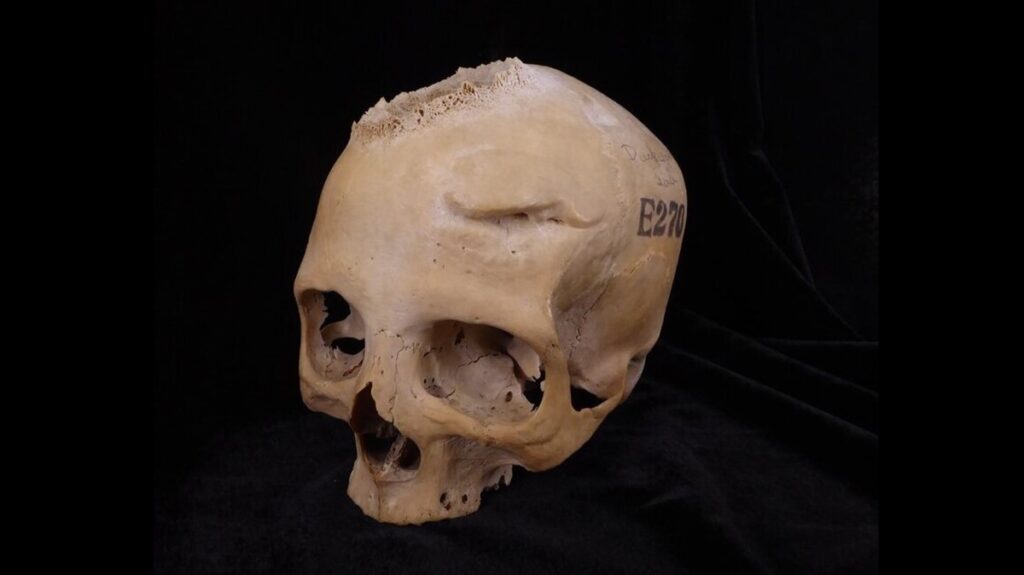

Skull E270 belonged to a female who was more than 50 years old when she died between 663 and 343 BCE, known as the Late Period of ancient Egypt sometime between the 26th and 30th dynasties.

Micro-CT scans of skull 236 showed a large lesion consistent with excessive tissue destruction, also known as neoplasm. In addition, the researchers found about 30 small, round metastasised lesions on the skull.

A series of cut marks around the lesions took the archaeologists by surprise.

“It seems ancient Egyptians performed some kind of surgical intervention related to the presence of cancerous cells, proving that ancient Egyptian medicine was also conducting experimental treatments or medical explorations in relation to cancer,” says co-author Albert Isidro from the University Hospital Sagrat Cor in Spain.

Similar lesions were found on skull E270 consistent with a cancerous tumour that led to bone destruction.

E270 also showed 2 healed traumatic injuries. It is possible the individual received treatment for the injuries.

“Was this female individual involved in any kind of warfare activities?” asks first author Tatiana Tondini from the University of Tübingen in Germany. “If so, we must rethink the role of women in the past and how they took active part in conflicts during antiquity.”

The finds suggest that cancer is not just a problem today with increased environmental factors and an older population.

“We wanted to learn about the role of cancer in the past, how prevalent this disease was in antiquity, and how ancient societies interacted with this pathology,” Tondini says. “We see that although ancient Egyptians were able to deal with complex cranial fractures, cancer was still a medical knowledge frontier.”

And it wasn’t just the ancient Egyptians. Ancient Roman physician Celsus, who died in 50 CE, wrote about the disease’s return after being cut out. Ancient Greek doctors Galen and Hippocrates considered it incurable.

Lead author Edgard Camarós, from Spain’s University of Santiago de Compostela, says more research is needed to uncover ancient medical practices.

“This study contributes to a changing of perspective and sets an encouraging base for future research on the field of paleo-oncology, but more studies will be needed to untangle how ancient societies dealt with cancer.”

Today, cancer remains the second leading cause of death in the world, hence the scientific community’s focus on finding effective treatments and potential cures.