Ancient Egyptian Woman Diagnosed With Rheumatoid Arthritis

A joint Italian-Polish archaeological mission uncovered during their work at the Sheikh Mohammed site in Aswan the skeletal remains of a young woman who suffered rheumatoid arthritis.

The mission is part of the Aswan-Kom Ombo Archaeological Project (AKAP).

A study on the skeleton published in the International Journal of Paleopathology showed the woman whose skeleton has been discovered suffered one of the earliest cases of Rheumatoid Arthritis in ancient Egypt.

Mustafa Waziri, Secretary-General of the Supreme Council of Antiquities, underscored the importance of the discovery, which, he said, indicated the only instance of diagnosed rheumatoid arthritis in ancient Egypt on record and one of the oldest cases globally.

Waziri noted that further scientific studies will be conducted on the discovered skeleton, which provides incontrovertible scientific proof that Ancient Egyptians were aware of the existence of cases of rheumatoid arthritis.

“Although a clinical definition of the disease emerged only in the seventeenth century, the recent archaeological evidence suggests that cases of rheumatoid arthritis antedate the seventeenth century,” he pointed out.

Abdel-Monem Said, General Director of Aswan Antiquities, reported that studies on the discovered skeleton have shown that rheumatoid arthritis had affected joints on both sides of the body, from hands and feet to shoulders, elbows, wrists, and ankles. Said added that though the mission has scrutinized written and visual evidence for a clear indication of similar cases, it could not find any record of rheumatoid arthritis in ancient Egypt.

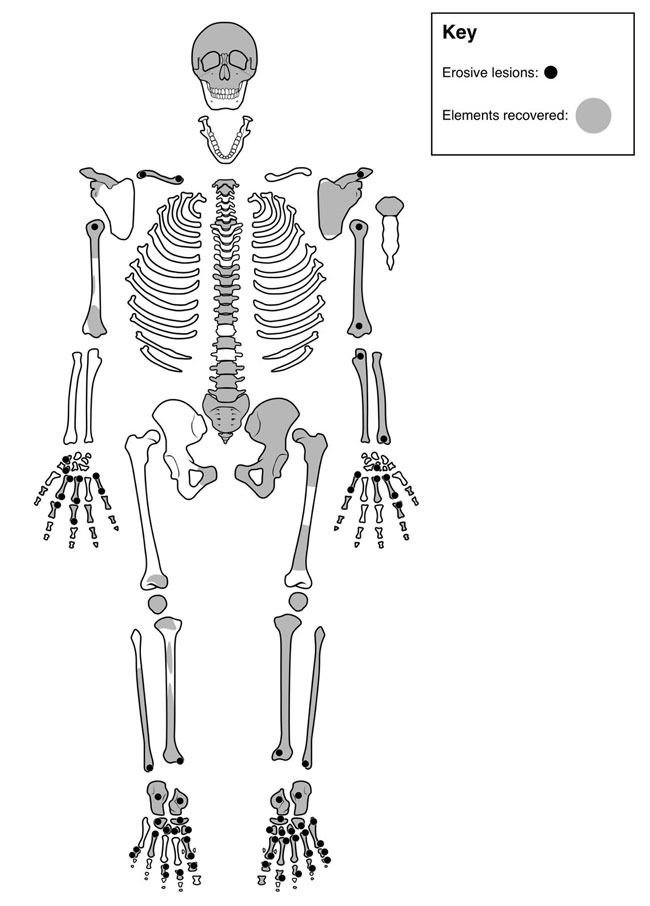

In their published study, the co-directors of the mission, Maria Carmela Gatto of the Polish Academy of Sciences and Antonio Corsi of the University of Bologna, said only 50-60 percent of the skeleton of the woman described in the study was recovered, adding that the examination of the fragmented skeleton showed that multiple joints were affected on both sides of the body, beginning with the hands and feet and moving on to the shoulders, elbow, wrists, and ankles.

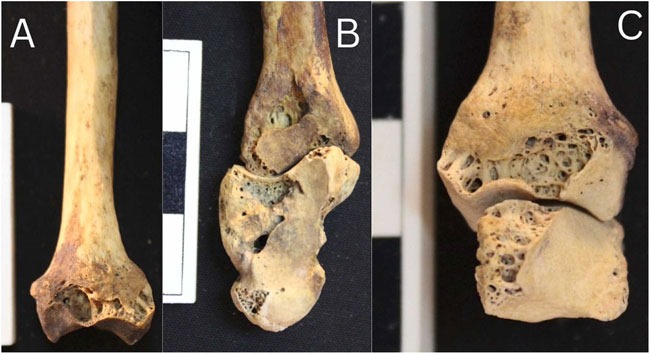

The two scientists explained that erosive lesions with smooth edges were found outside the joint surface. These lesions, they explained, would have led to “aches, stiffness, and swelling, all of which would have affected the joints’ ability to carry out daily activities.”

Furthermore, the co-directors of the mission explained in their study that with time, the person’s suffering would have intensified, raising the likelihood of developing other conditions such as heart disease, thus compromising the individual’s life expectancy and quality of life.

On the other hand, paleopathologists Madeleine Mant of the University of Toronto in Ontario and Mindy Pitre of St. Lawrence University in New York, who contributed to the study, said rheumatoid arthritis, which is the most common form of inflammatory arthritis occurring in 0.5–1 percent of the global adult population, typically emerges between the ages of 30 and 50.

They explained that this chronic inflammatory autoimmune condition affects the lining of joints and various body parts, including the skin, eyes, mouth, heart, and lungs.

Given its autoimmune nature, the body’s immune system targets its tissues, resulting in inflammation of the joints as well as pain, disability, and eventual early death, Mant and Pitre noted, adding that while the exact cause of the condition is unknown, factors such as biological sex, smoking, family history, genetics, and exposure to certain bacteria and viruses increase one’s risk of developing the condition.

In addition, the two scientists pointed out that although there are multiple treatment options today, few, if any, would have been available during the Second Intermediate Period in Egypt (c.1800–1500 BCE),

“A clear consensus has yet to be reached on the origin and antiquity of rheumatoid arthritis,” they said in a statement, highlighting that some researchers believe there is enough archaeological and historical evidence to suggest its existence in Afro-Eurasia before the 17th century while others have argued that such evidence remains controversial, suggesting instead that the condition originated in the Americas.

“This new case from Aswan provides strong evidence in support of the former hypothesis,” Mant and Pitre asserted, adding that even though skeletal remains from ancient Egypt had indicated in the late 19th and the early 20th centuries the presence of some of the earliest cases of rheumatoid arthritis, the cases were dismissed on the grounds of imprecise diagnostic criteria.

Since then, examples of possible cases have been described from prehistorical and historical contexts in North America, Europe, and Asia, several of which remain contentious, according to both scientists.

Similarly, Mant and Pitre asserted that scholars have also examined written and pictorial evidence for signs of the condition. They noted that although a lack of textual mention of rheumatoid arthritis in ancient Egypt suggested that the condition in its present form did not exist at the time in Egypt, the recent discovery from Aswan provides clear evidence for the presence of the condition in ancient Egypt.

The AKAP project, which began in 2005, aims to study the health conditions of ancient Egyptians, especially those belonging to the lower strata of society and residing on the outskirts of the ancient Egyptian state, such as in the far south.

The project focuses on archaeological surveys and documentation of prehistoric areas; it is affiliated with the University of Bologna in collaboration with the Institute of Mediterranean and Oriental Cultures – Polish Academy of Sciences.

In 2016, the mission discovered the earliest case of vitamin C deficiency in the skeleton of a young child found in a village dated to the Predynastic period (3800–3500 BCE). A study of this case was also published in the International Journal of Paleopathology.