“Arabian Stonehenge” Uncovered in Oman Desert

Handaxes from the period of the first human migration out of Africa, circular burial chambers, a collection of rock engravings, and the Arabian Stonehenge. Unique findings are being reported by an international team led by the Institute of Archaeology of the CAS in Prague, which has successfully completed its third excavation season in Oman. The collected samples are now being analyzed by experts and will contribute to the reconstruction of the earliest history of the world’s largest sand desert.

Czech archaeologists have been focusing on the still underexplored desert areas of the Sultanate of Oman for a long time. Their last year’s expedition was the third in a row and several more are in the pipeline. More than twenty archaeologists and geologists from ten countries were involved in the excavations at two different sites in Oman.

The first expedition team was situated in the Dhofar Governorate in the south of the country, while the second group operated in the Duqm province of central Oman. The researchers shared their observations directly from the field on Twitter via @Arduq_Arabia.

The Arabian Peninsula as a migration corridor

In the dunes of the Rub’ al Khali desert in the Dhofar province, researchers unearthed stone handaxes that date back to the first human migration out of Africa some 300,000 to 1.3 million years ago. Due to its geographical location, Arabia served as a natural migration route from the African cradle of humankind into Eurasia.

Among dunes up to 300 meters high, they managed to find eggshells of extinct ostriches, a fossil dune, and an old riverbed from a period when the climate in Arabia was significantly wetter. “Our findings, supported by four different dating methods, will provide valuable data for reconstructing the climate and history of the world’s largest sand desert. Natural conditions also shaped prehistoric settlements, and what we are trying to do is study human adaptability to climate change,” said expedition leader and coordinator Roman Garba from the Institute of Archaeology of the CAS in Prague.

Nuclear physics is helping history research

Archaeologists use special dating methods to determine the age of the finds. “We carry out radiocarbon dating and cosmogenic radionuclide dating in cooperation with the Nuclear Physics Institute of the CAS, which has newly commissioned the first accelerator mass spectrometer in the Czech Republic,” Garba explained.

Radiocarbon dating and spatio-temporal analysis can also help researchers find out more about the roughly two-thousand-year-old ritual stone monuments – known as triliths. In layman’s terms, they can be likened to England’s better-known Stonehenge. They appear in what is now southern Arabia, and it is not clear exactly what they were used for or who built them.

What is hidden beneath the circular burial chambers?

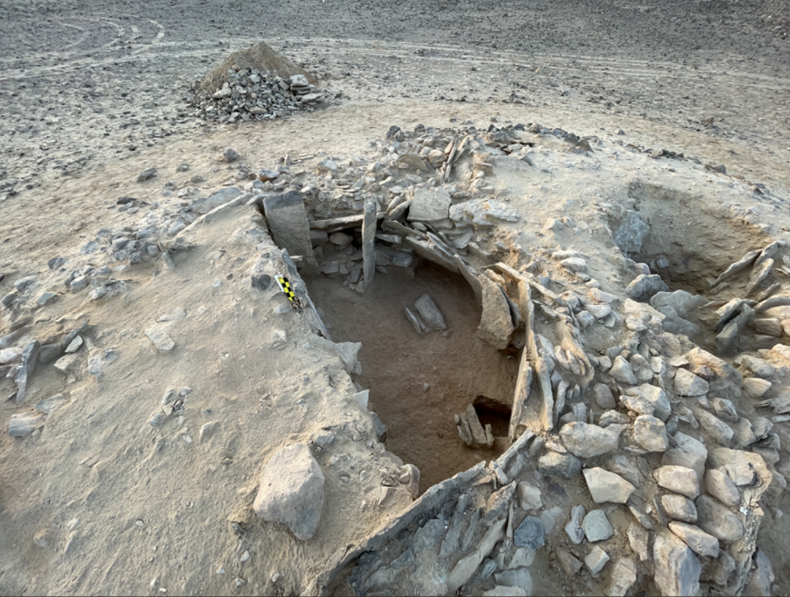

The second expedition team operated in the Duqm province of central Oman, focusing in particular on a Neolithic tomb dating back to 5,000–4,600 BCE at the Nafūn site.

“What we find here is unique in the context of the whole of southern Arabia. A megalithic structure concealing two circular burial chambers revealed the skeletal remains of at least several dozen individuals. Isotopic analyses of bones, teeth, and shells will help us to learn more about the diet, natural environment, and migrations of the buried population,” explains Alžběta Danielisová from the Institute of Archaeology, Prague.

“What we find here is unique in the context of the whole of southern Arabia. A megalithic structure concealing two circular burial chambers revealed the skeletal remains of at least several dozen individuals.

Isotopic analyses of bones, teeth, and shells will help us learn more about the diet, natural environment, and migrations of the buried population,” explained Alžběta Danielisová from the Institute of Archaeology of the CAS in Prague.

Not far from the tomb, there is a unique collection of rock engravings spread out over a total of 49 rock blocs, whose different styles and varying degrees of weathering provide a pictorial record of settlements from 5,000 BCE to 1,000 CE. Researchers also investigated stone tool production sites from the Late Stone Age.

Following the traces of ancient settlements in southern Arabia

The research in Oman is part of a wider project by evolutionary anthropologist Viktor Černý from the Institute of Archaeology in Prague. His research focuses on the biocultural interactions of populations and their adaptation to climate change.

“The detected interactions of African and Arab archaeological cultures characterize the mobility of populations of anatomically modern humans.

It will be interesting to confront these findings also with the genetic diversity of the two regions and create a more comprehensive view of the formation of contemporary society in Southern Arabia,” explained Černý, who received the prestigious Academic Award of the Czech Academy of Sciences for the project last year.

The ARDUQ (Archaeological Landscape and environmental dynamics of Duqm and Nejd) expedition was carried out under the auspices of the Omani Ministry of Heritage and Tourism. Researchers from the Czech Republic, USA, Great Britain, Ukraine, Iran, Italy, Slovakia, Austria, France, and Oman took part in the project.