Archaeologists Discover Homes Of The Builders Of Europe’s First Monuments Made 6,400 Years Ago

Archaeologists in France have found one of the first residential sites belonging to the prehistoric builders of some of Europe’s first monumental stone structures.

During the Neolithic, people in west-central France built many impressive megalithic monuments such as barrows and dolmens.

While these peoples’ tombs stood the test of time, archaeologists have been searching for their homes for more than a century.

“It has been known for a long time that the oldest European megaliths appeared on the Atlantic coast, but the habitats of their builders remained unknown,” said Dr. Vincent Ard from the French National Center for Scientific Research.

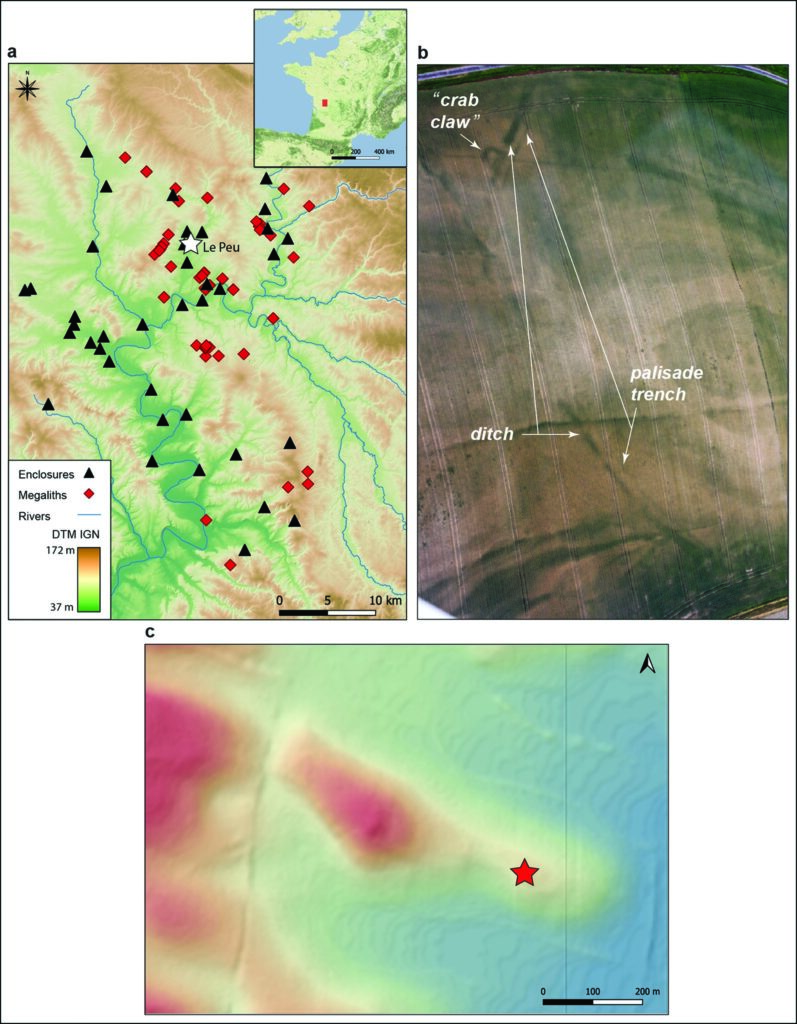

Now, Dr. Ard and a team of researchers working in the Charente department have identified the first known residential site belonging to some of Europe’s first megalithic builders.

The Le Peu enclosure was discovered during an aerial survey in 2011 and has since been the subject of intense research.

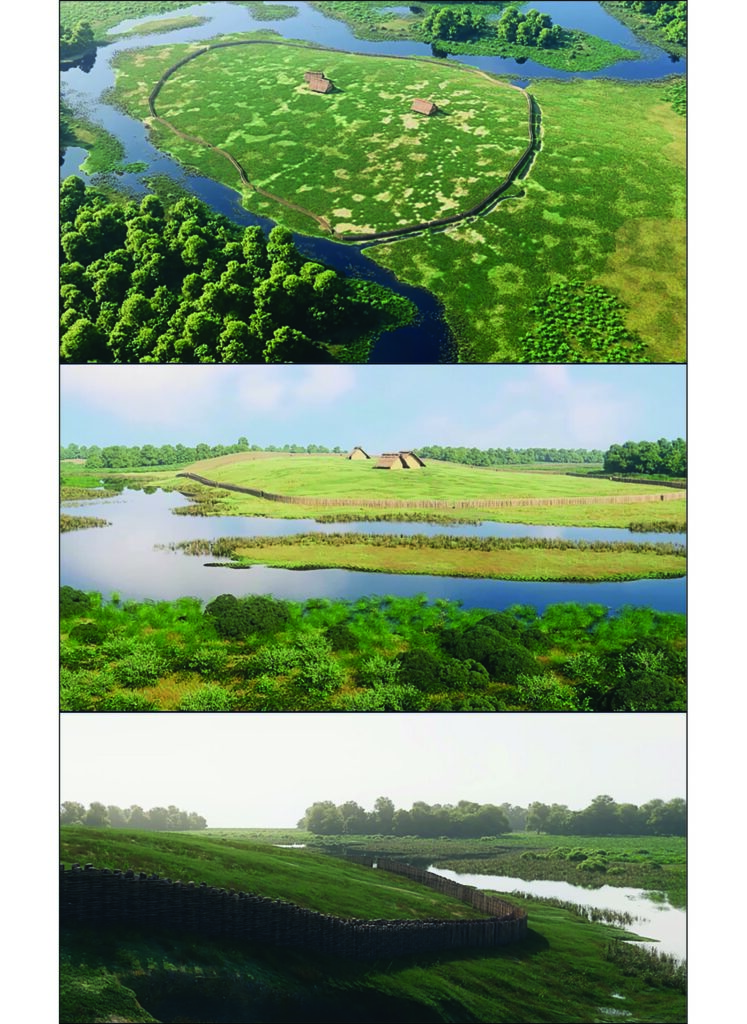

The results of this work, published in the journal Antiquity, revealed a palisade encircling several timber buildings built during the fifth millennium BC.

This makes them the oldest wooden structures in the region and the first residential site contemporary with the Neolithic monument makers. At least three homes were found, each around 13 meters long, clustered together near the top of a small hill enclosed by the palisade.

From his hill, the nearby Tusson megalithic cemetery would be visible. This raised the possibility that the inhabitants of Le Peu built the site’s five long mounds. To test this, the archaeologists carried out radiocarbon dating that revealed these monuments are contemporary with Le Peu, suggesting the two sites are linked.

While the people of Le Peu may have built monuments to the dead, they also invested a lot of time and effort in protecting the living. Analysis of the paleosol recovered from the site revealed it was located on a promontory bordered by a marsh. These natural defenses were enhanced by a ditch palisade wall which extended around the site.

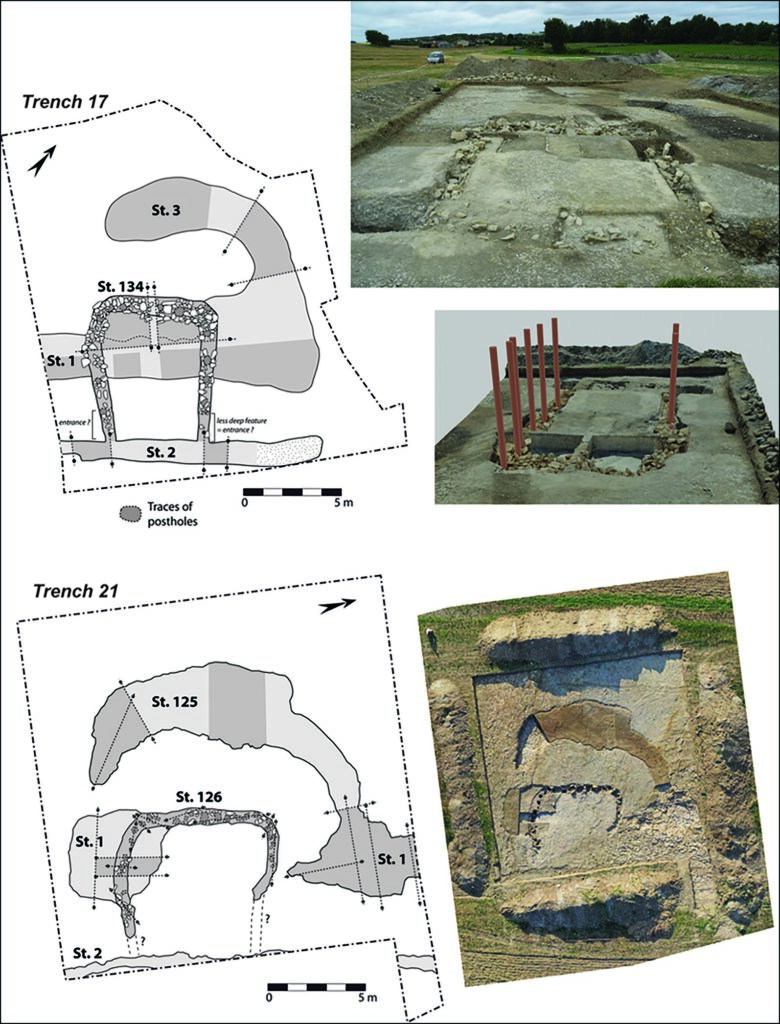

The entrance had particularly heavy defenses, guarded by two monumental structures.

These appear to have been later additions, requiring part of the defensive ditch to be filled in.

“The site reveals the existence of unique monumental architectures, probably defensive. This demonstrates a rise in Neolithic social tensions,” said Dr. Ard.

However, these impressive defenses may have proved insufficient as all the buildings at Le Peu appear to have been burnt down around 4400 BC. However, such destruction helped preserve the site.

As such, Dr. Ard and the team hope further research at Le Peu will continue to shed light on the lives of people only known from their monuments to the dead. Already it shows how their residential sites had a monumental scale, never before seen in prehistoric Atlantic society.