Mystery of the unbreached burial chamber Inside the little-known Dahshur pyramid in Egypt

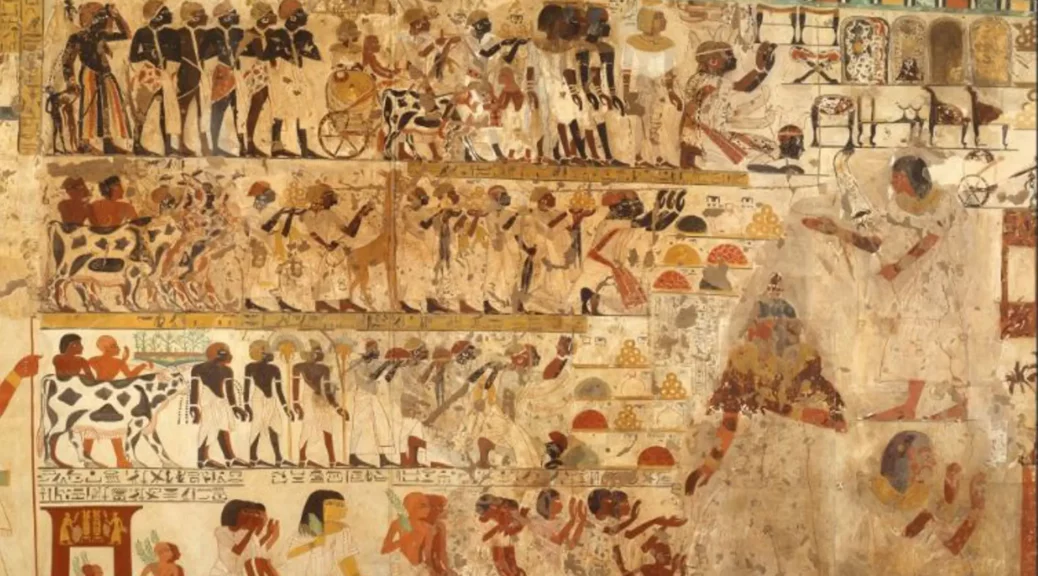

The enduring mysteries of ancient Egypt keep fascinating archaeologists, historians, and the public alike. The Land of the Pharaohs refuses to give up its secrets, and despite countless magnificent archaeological finds, we tend to encounter riddles all over Egypt. Buried beneath the sands lie the tremendous treasure of one of the most powerful ancient civilizations of all time, the ancient Egyptians.

Sometimes archaeologists arrive too late at the site, leaving us with ancient mysteries that may never be solved. That is the beauty but tragedy of ancient Egyptian history. Magnificent ancient tombs have long been looted, and we may never know to whom the burial places belonged.

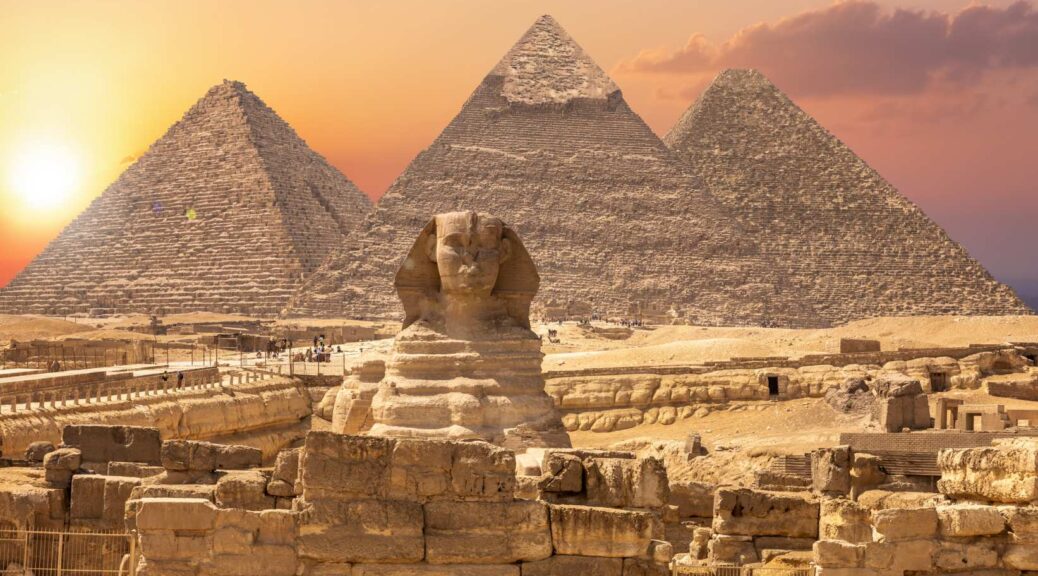

Located about 15 miles south of Cario, the Dahshur complex is famous for its incredible structures constructed during the era of the Old Kingdom. Dahshur there a series of pyramids, mortuary temples, and other buildings that still remain unexplored.

Archaeologists have long argued that sites such as Dahshur, along with Giza, Lisht, Meidum, and Saqqara are significant as archaeological findings made there “would confirm or adjust the entire time frame of the extraordinary developmental phase of Egyptian civilization that saw the biggest pyramids built, the nomes (administrative districts) organized, and the hinterlands internally colonized – that is, the first consolidation of the Egyptian nation state.”

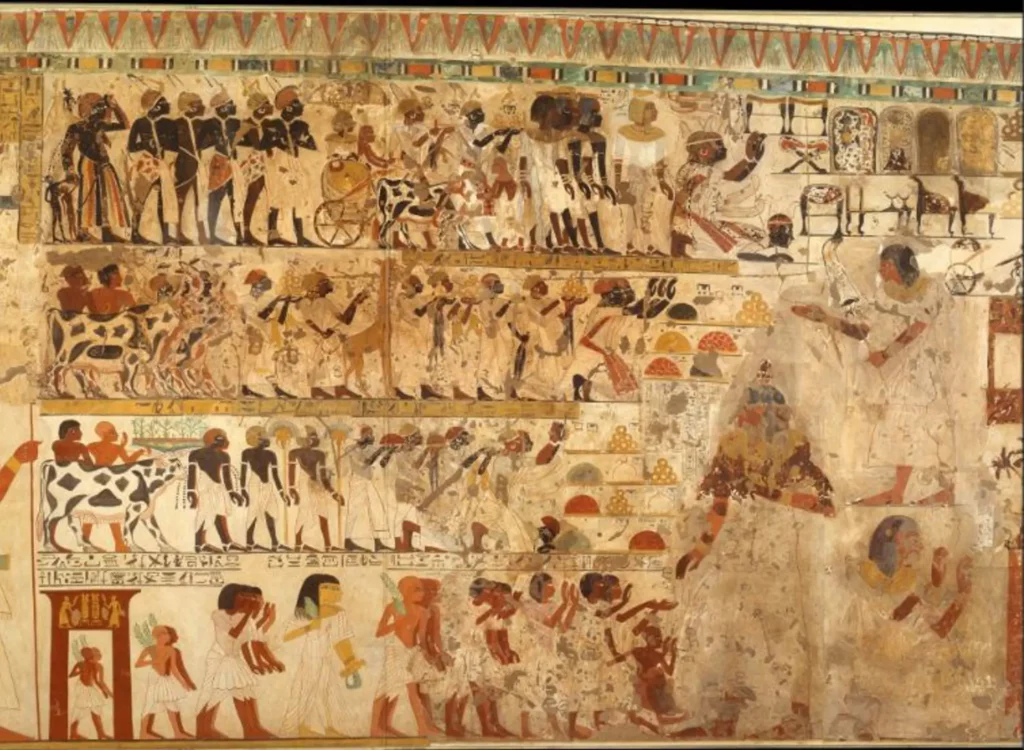

In addition to this information, the results of such excavation projects would naturally also fill in the historical gaps and provide a more comprehensive picture of the life and deaths of pharaohs and ordinary people in ancient Egypt.

Many ancient Egyptian pyramids have been destroyed, but several are hidden beneath the sands awaiting scientific exploration. One such intriguing ancient structure is the newly-discovered pyramid in Dahshur, a previously inaccessible site relatively unknown to the public.

Dahshur is an ancient necropolis known mainly for several pyramids, two of which are among the oldest, largest, and best-preserved in Egypt, built from 2613–2589 BC. Two of the Dahshur Pyramids, the Bent Pyramid, and the Red Pyramid, were constructed during the reign of Pharaoh Sneferu (2613-2589 BC).

The Bent Pyramid was the first attempt at a smooth-sided pyramid, but it was not a successful achievement, and Sneferu decided to build another called the Red Pyramid. Several other pyramids of the 13th Dynasty were built at Dahshur, but many are covered by sand, almost impossible to detect.

In 2017, Dr Chris Naunton, President of the International Association of Egyptologists, traveled to Dahshur together with the crew of the Smithsonian Channel and documented the exciting findings of one particular pyramid.

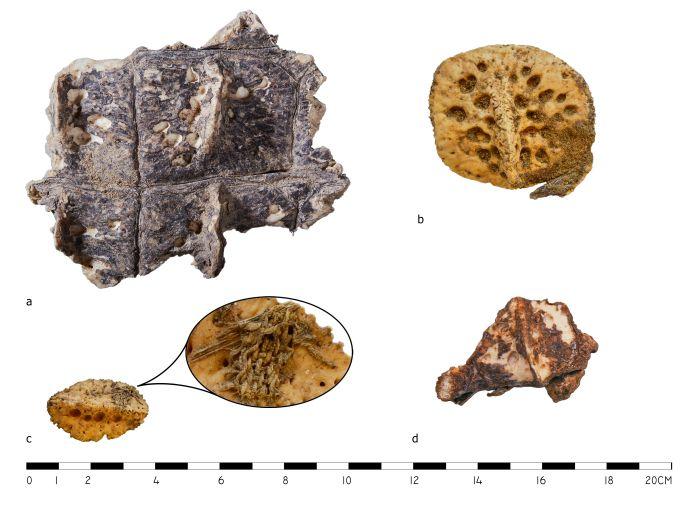

What the team discovered is a bit like an ancient detective story. Local archaeologists had found heavy blocks of finely cut limestone buried deep in the sand. Egypt’s Ministry of Antiquity was informed about the discovery, and archaeologists were sent to the site to excavate.

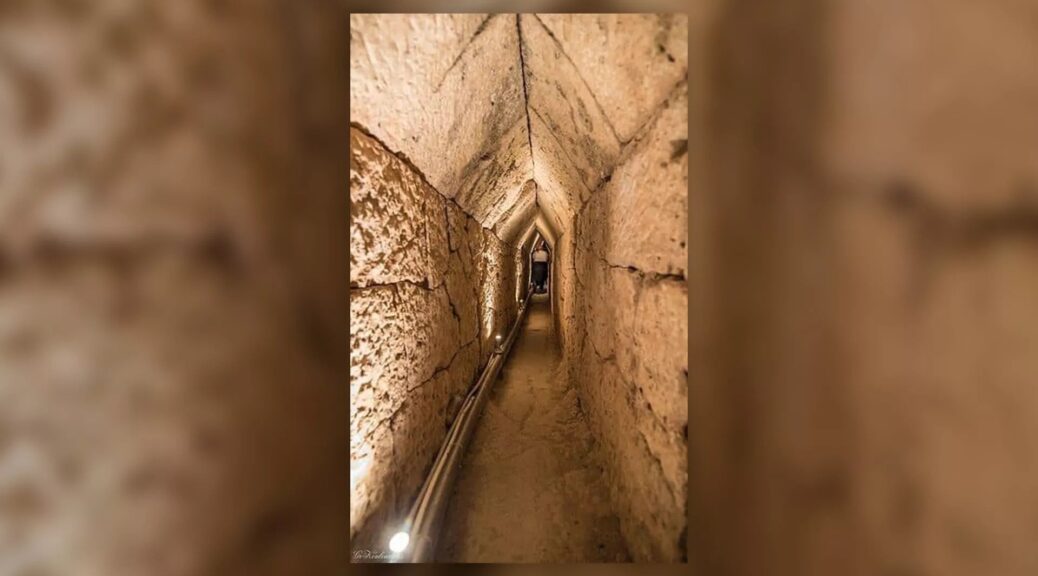

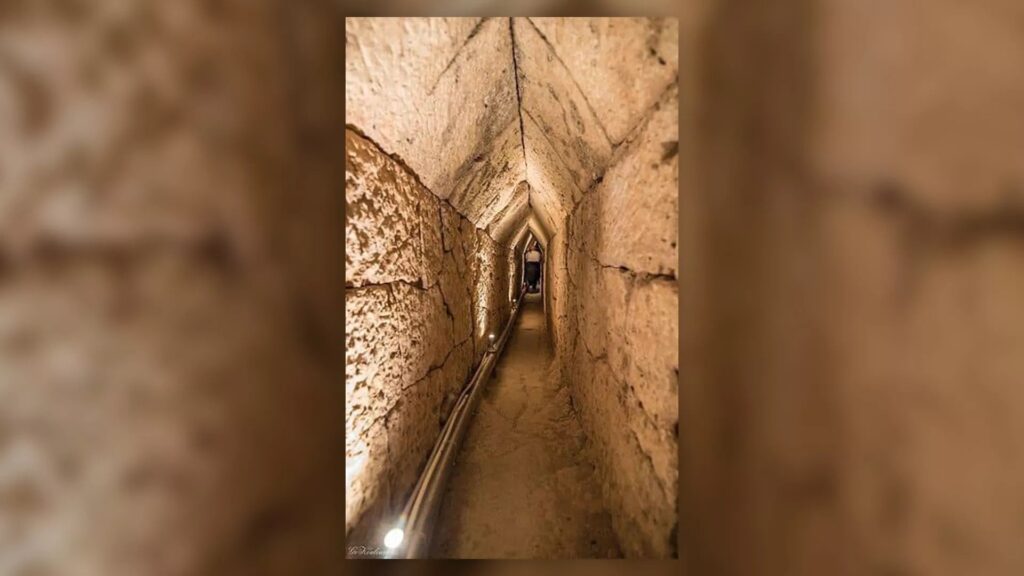

Having worked long and hard, archaeologists finally uncovered a previously unknown pyramid. Still, the most exciting part was the discovery of a secret passage that led from the pyramid’s entrance to an underground complex at the very heart of the pyramid. The chamber was protected by heavy and huge limestone blocks ensuring no one could pass easily and explore whatever was hidden inside the mysterious ancient pyramid.

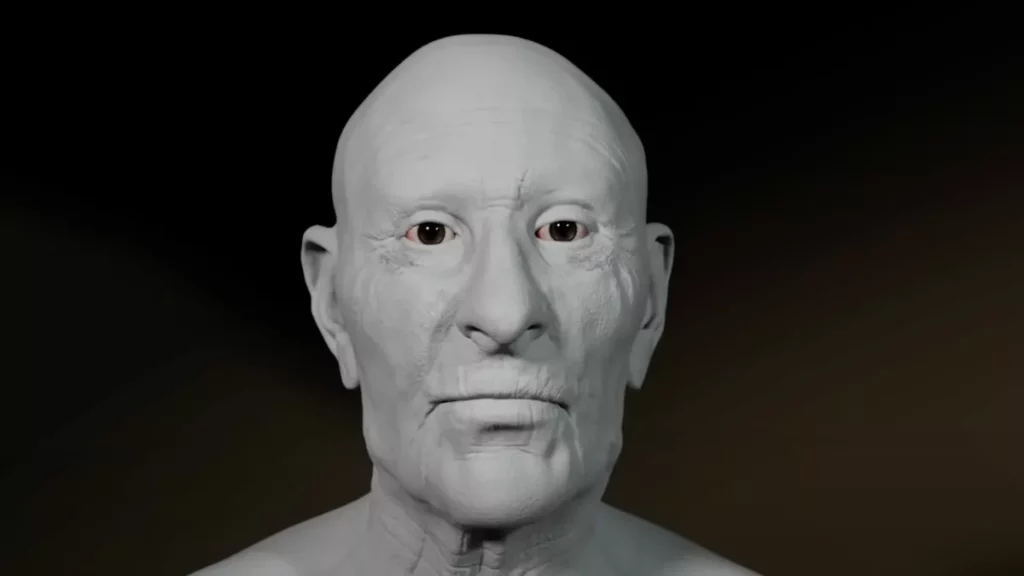

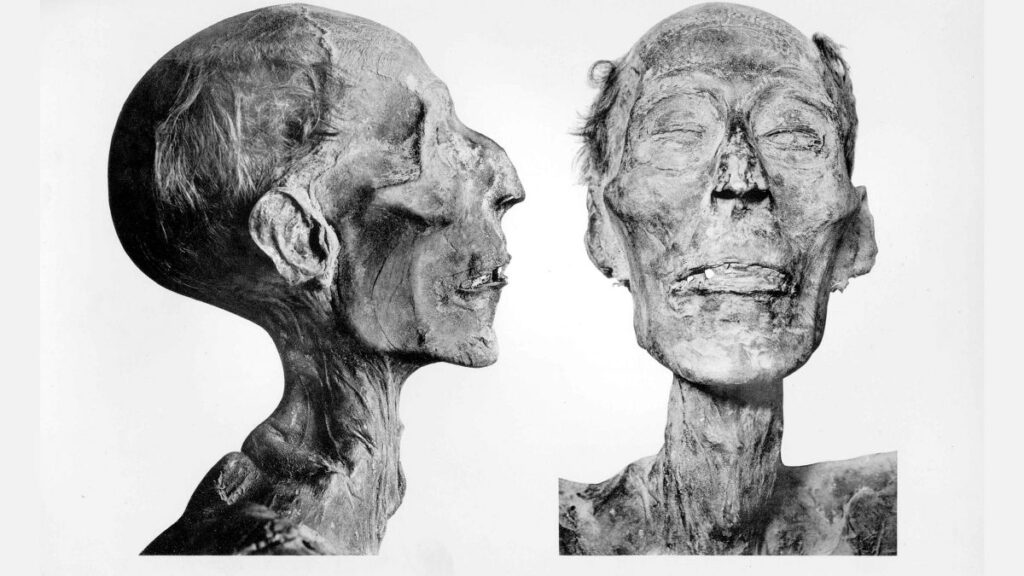

The obstacles did not discourage archeologists successfully after some days of work managed to enter the interior of the pyramid. Everything seemed to indicate the unknown pyramid at Dahshur contained ancient treasures and most likely a mummy.

When scientists found themselves inside the burial chamber they were astounded to see someone had visited this ancient place long before them. The Dahshur pyramid had been robbed about 4,000 years ago. Looting of pyramids in the past was quite common, and the Dahshur pyramid was one of many victims of robbery.

One can understand Dr. Naunton’s disappointment when he glanced into the empty burial chamber, but the fact remains this discovery is intriguing and raises specific questions.

“There are two questions here that we need to start trying to answer. One is who was buried here? Who was this pyramid built for? And then secondly, how is it that an apparently completely sealed, unbreached burial chamber comes to have been disturbed?” Dr. Nauton says.

Was a mummy stolen from the Dahshur pyramid? How did looters get past the untouched seal? Did the original ancient builders plunder the burial chamber before they sealed it? These are some of the many questions this ancient Egyptian mystery pose.