Ancient Egyptian Mummy Linen Fragments Seized in Michigan

U.S. border officials say they have seized ancient Egyptian mummy linens during enforcement operations at the Blue Water Bridge that connects Port Huron, Mich., to Sarnia, Ont.

Five containers containing the artifacts were seized on May 25 following the selection of the truck for examination in Michigan near Sarnia, Ont., the U.S. Customs and Border Protection said.

The artifacts had come from Canada in a bulk mail shipment, and were being shipped to a home in the United States, Kris Grogan, spokesman for the agency, said in an interview.

“It’s taken some time to identify what they were,” Grogan said. “We’ve had to work with the State Department as well as other federal agencies in identifying this.”

The artifacts would be sent back to Egypt in the near future, Grogan said.

In a statement, the agency said the importer was unable to prove the linens had been taken out of Egypt before 2016.

That could be a violation of the U.S. Convention on Cultural Property Implementation Act, a federal law that allows American authorities to impose import restrictions on certain classes of archeological material.

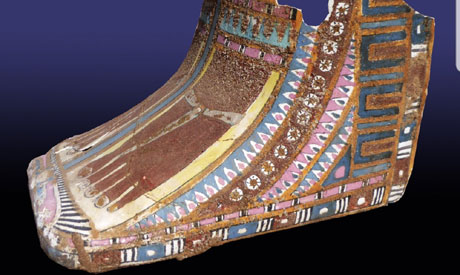

Authorities said they worked with an unidentified archeological organization to pin down the age of the artifacts, which are believed to date back to the Ptolemaic Dynasty from 305-30 B.C.

One expert in antiquities, Sue McGovern-Huffman, said trying to illegally buy ancient artifacts is more trouble than it’s worth no matter what era the object is from.

“If it’s been illegally taken out of the country, it’s got a zero value as far as the commercial market is concerned,” McGovern-Huffman, president of Sands of Time Antiquities, said from Washington, D.C.

Without an artifact’s provenance or proof of ownership and history, even illegally selling ancient artifacts would be difficult for any dealer on the black market, she said.

McGovern-Huffman, an accredited member of the International Society of Appraisers, said pieces like ancient mummy linens have more archeological or study interest than collector interest.

“These fragments have very little value. There are all these reports of antiquities selling for millions and billions of dollars on the black market and it’s completely wrong,” she said. “You’d be lucky to get $50 for this stuff.”

Michael Fox, the customs agency director in Port Huron, Mich., said the seizure was of “historical importance.”

Grogan said no arrests have been made as it remains unclear who might be criminally responsible.