Archaeologists Unearth Colossal Pair of Sphinxes in Egypt During Restoration of Landmark Temple

A pair of giant limestone sphinxes have been unearthed by archaeologists excavating the temple of Amenhotep III, who ruled ancient Egypt about 3,300 years ago and was the grandfather of Tutankhamun.

The statues depict the pharaoh wearing a mongoose-shaped headdress, a royal beard and a wide necklace. After further analysis, the team found the script ‘the beloved of Amun-Re’ across one of the sphinx’s chests.

The Egyptian-German archaeological team, led by Horig Sorosian, found the colossal statues submerged in water at the funerary building, known as the ‘Temple of Millions of Years,’ according to the Egyptian Ministry of Tourism and Antiquities.

The temple is in Luxor, Egypt, which is famously known for the oldest and most ancient Egyptian sites, along with being home to the Valley of Kings.

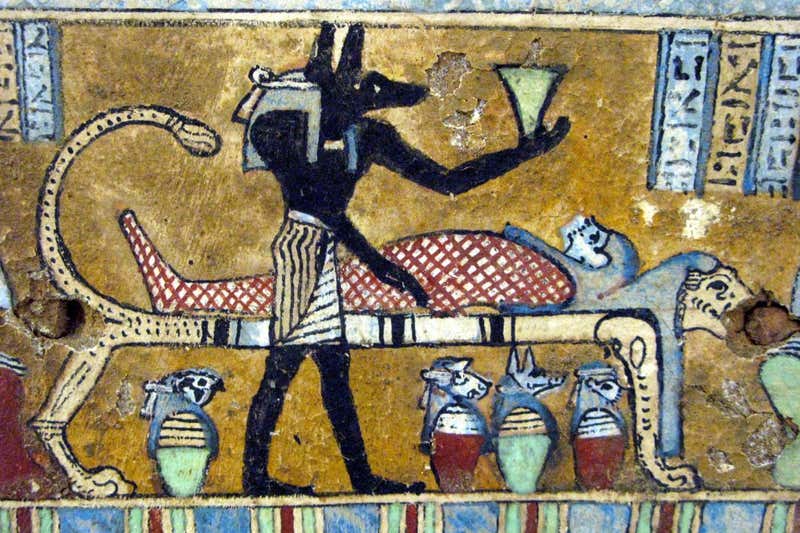

Along with the 26-foot-long sphinxes, the team also uncovered three nearly intact statues of the goddess Sekhmet, the lion-like defender of the Sun god Ra and the remains of a great pillared hall.

And the walls throughout the hall are decorated with ceremonial and ritual scenes. Horosian emphasized the importance of this discovery, as the two sphinxes confirm the presence of the beginning of the procession road where the celebrations of the Beautiful Valley Festival were held every year.

This yearly event was a time when people could visit their deceased loved ones and bring them gifts – and it was only celebrated in the ancient city of Thebes.

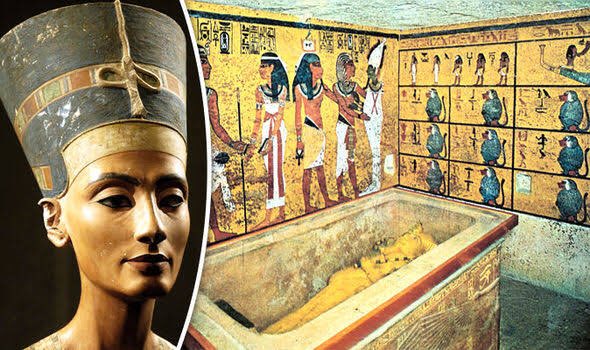

King Amenhotep III was the grandfather of the famed boy-pharaoh Tutankhamun and ruled in the 14th century BC at the height of Egypt’s the New Kingdom and presided over a vast empire stretching from Nubia in the south to Syria in the north.

The 18th dynasty ruler became king aged around 12, with his mother as regent and is believed to have ruled Egypt between 1386 and 1349 BC. Amenhotep III chose the daughter of a provincial official as his royal wife, and throughout his reign, Queen Tiy featured alongside the king.

Amenhotep III died in around 1354 BC and was succeeded by his son Amenhotep IV, widely known as Akhenaten, who was King Tut’s father.

Tut began his reign at the age of eight or nine and ruled for about nine years. However, the young king was plagued with health issues due to his parents being brother and sister – and experts believe the issues led to his death.

Amenhotep III may have left the Earth thousands of years ago, but archaeologists are still uncovering remnants of his past, with the most lavish being the ‘lost golden city.’

In April 2021, archaeologists announced the discovery of a 3,500-year-old city in Luxor, which they said is the largest ancient city ever to be discovered in Egypt.

It was built by Amenhotep III and later used by King Tutankhamun. Luxor, a city of some 500,000 people on the banks of the Nile in southern Egypt, is an open-air museum of intricate temples and pharaonic tombs.

Excavations at the site uncovered bakeries, workshops and burials of animals and humans, along with jewellery, pots and mud bricks bearing seals of Amenhotep III.

The team initially set out to discover Tutankhamun’s Mortuary Temple, where the young king was mummified and received status rites, but they stumbled upon something far greater.

Betsy Brian, Professor of Egyptology at John Hopkins University in Baltimore USA, said ‘The discovery of this lost city is the second most important archaeological discovery since the tomb of Tutankhamun’.

‘The discovery of the Lost City, not only will give us a rare glimpse into the life of the Ancient Egyptians at the time when the Empire was at its wealthiest but will help us shed light on one of history’s greatest mysteries: why did Akhenaten & Nefertiti decide to move to Amarna.’

The city sits between Rameses III’s temple at Medinet Habu and Amenhotep III’s temple at Memnon. Excavations began in September 2020 and within weeks, archaeologists uncovered formations made of mud bricks.

After more digging, archaeologists unearthed the site of the large, well-preserved city with almost complete walls, and rooms filled with tools once used by the city’s inhabitants.