An amazing discovery in Egypt – The bones of a 3600-year-old giant palm

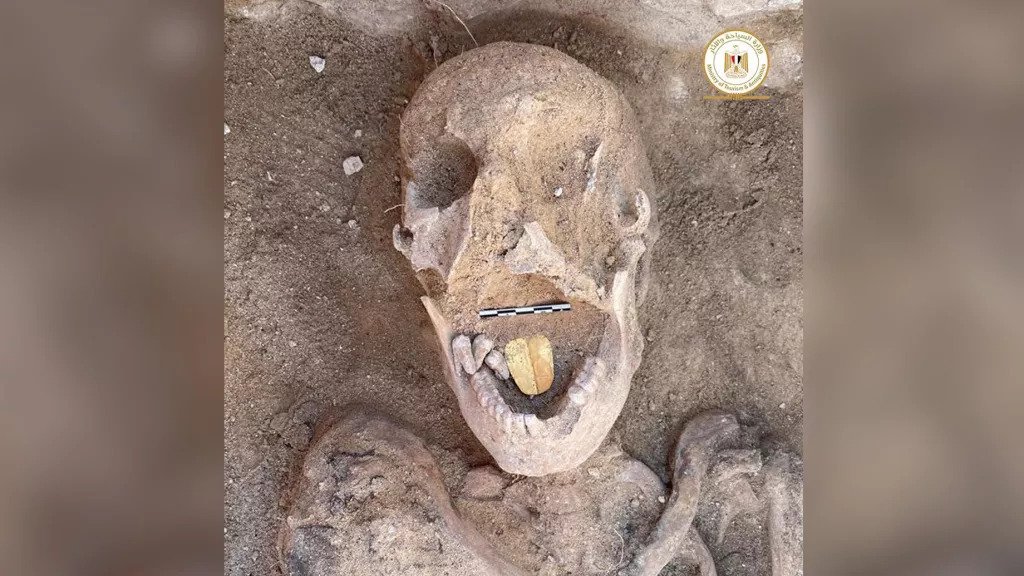

A team of archaeologists has found that one of the palaces in the ancient city of Avaris, in Egypt, has hundreds of human sacrifices hidden beneath the earth. Archaeologists in the past have excavated the skeletons of 16 human hands that were found in four pits.

Two of the pits, located in front of what is believed to be a throne room, hold one hand each. Two other pits, constructed at a slightly later time in outer space of the palace, contain the 14 remaining hands.

They are all right hands; there are no lefts.

“Most of the hands are quite large and some of them are very large,” Manfred Bietak, project and field director of the excavations, told LiveScience.

The finds, made in the Nile Delta northeast of Cairo, date back about 3,600 years to a time when the Hyksos, a people believed to be originally from northern Canaan, controlled part of Egypt and made their capital at Avaris a location known today as Tell el-Daba. At the time the hands were buried, the palace was being used by one of the Hyksos rulers, King Khayan.

The hands appear to be the first physical evidence of a practice attested to in ancient Egyptian writing and art, in which a soldier would present the cut-off right hand of an enemy in exchange for gold, Bietak explains in the most recent edition of the periodical Egyptian Archaeology.

“Our evidence is the earliest evidence and the only physical evidence at all,” Bietak said. “Each pit represents a ceremony.”

Cutting off the right hand, specifically, not only would have made counting victims easier, it would have served the symbolic purpose of taking away an enemy’s strength.

“You deprive him of his power eternally,” Bietak explained. It’s not known whose hands they were; they could have been Egyptians or people the Hyksos were fighting in the Levant. “Gold of valor”

Cutting off the right hand of an enemy was a practice undertaken by both the Hyksos and the Egyptians.

One account is written on the tomb wall of Ahmose, son of Ibana, an Egyptian fighting in a campaign against the Hyksos. Written about 80 years later than the time the 16 hands were buried, the inscription reads in part:

“Then I fought hand to hand. I brought away a hand. It was reported to the royal herald.” For his efforts, the writer was given “the gold of valor” (translation by James Henry Breasted, Ancient Records of Egypt, Volume II, 1905). Later, in a campaign against the Nubians, to the south, Ahmose took three hands and was given “gold in double measure,” the inscription suggests.

Scientists are not certain who started this gruesome tradition. No records of the practice have been found in the Hyksos’ likely homeland of northern Canaan, Bietak said, so could have been an Egyptian tradition they picked up, or vice versa, or it could have originated from somewhere else.

Bietak pointed out that, while this find is the earliest evidence of this practice, the grisly treatment of prisoners in ancient Egypt was nothing new.

The Narmer Palette, an object dating to the time of the unification of ancient Egypt about 5,000 years ago, shows decapitated prisoners and a pharaoh about to smash the head of a kneeling man.

The archaeological expedition at Tell el-Daba is a joint project of the Austrian Archaeological Institute’s Cairo branch and the Austrian Academy of Sciences.