Homo erectus Fossils and Tools Unearthed in Ethiopia

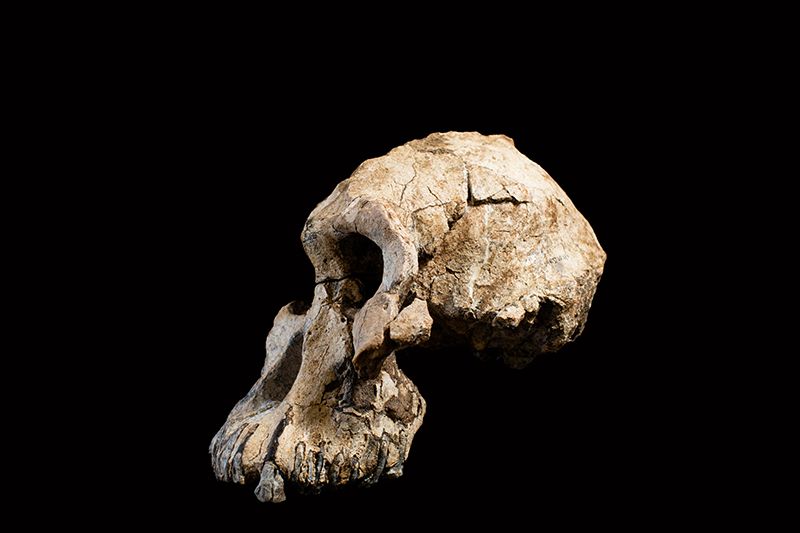

Africa’s smallest Homo erectus cranium and the various stone tools discovered in Gona, Ethiopia, indicate that human ancestors were more varied, both physically and behaviorally, than previously known.

A Cranium was discovered by an international study team headed by the U.S. and Spanish scientists, including a Michigan geologist university, An almost complete hominin cranium is estimated to 1.5 million years, and a partial cranium dated to 1.26 million years ago, from the Gona study area, in the Afar State of Ethiopia discovered by international study team.

All cranies that are assigned to Homo erectus were associated with simple Oldowan-type (Mode 1) and more complex Acheulian (Mode 2) stone tool assemblages. This suggests that H. Erectus had a degree of cultural/behavioral plasticity that has yet to be fully understood.

The team was led by Sileshi Semaw of CENIEH (Centro Nacional de Investigación Sobre la Evolución Humana) in Spain and Michael Rogers of Southern Connecticut State University. U-M geologist Naomi Levin coordinated the geological work to determine the age of the fossils and their environmental context.

The nearly complete cranium was discovered at Dana Aoule North (DAN5), and the partial cranium at Busidima North (BSN12), sites that are 5.7 kilometers apart. The research team has been investigating the Gona deposits since 1999, and the BSN12 partial cranium was discovered by N. Toth of Indiana University during the first season.

The DAN5 cranium was found a year later by the late Ibrahim Habib, a local Afar colleague, on a camel trail. The BSN12 partial cranium is robust and large, while the DAN5 cranium is smaller and more gracile, suggesting that H. Erectus was probably a sexually dimorphic species. Remarkably, the DAN5 cranium has the smallest endocranial volume documented for H. Erectus in Africa, about 590 cubic centimeters, probably representing a female.

The smallest Homo erectus cranium in Africa, and the diverse stone tools found at Gona, show that human ancestors were more varied, both physically and behaviorally, than previously known, according to the researchers.

This physical diversity is mirrored by the stone tool technologies exhibited by the artifacts found in association with both crania. Instead of only finding the expected large handaxes or picks, signature tools of H. Erectus, the Gona team found both well-made handaxes and plenty of less-complex Oldowan tools and cores.

The toolmakers at both sites lived in close proximity to ancient rivers, in settings with riverine woodlands adjacent to open habitats. The low d13C isotope value from the DAN5 cranium is consistent with a diet dominated by C3 plants (trees and shrubs, and/or animals that ate food from trees or shrubs) or, alternatively, broad-spectrum omnivory.

The ages of the fossils and the associated artifacts were constrained using a variety of techniques: standard field mapping and stratigraphy, as well as analyses of the magnetic properties of the sediments, the chemistry of volcanic ashes, and the distribution of argon isotopes in volcanic ashes.

“Constraining the age of these sites proved particularly challenging, requiring multiple experts using a range of techniques over several years of fieldwork,” said Levin, an associate professor in the U-M Department of Earth and Environmental Sciences and in the Program in the Environment.

“This is a great example of scientific detective work and how science gets done, drawing on a community of scholars and their collective knowledge of the geology of eastern Africa,” said Levin, who co-directs an isotope geochemistry lab that conducts studies of ancient environments using carbon and oxygen isotopes.

Along with the University of Arizona geologist Jay Quade, Levin also coordinated the environmental reconstruction of the Gona sites. At the Gona study area in Ethiopia’s Afar State, H. Erectus used locally available stone cobbles to make their tools, which were accessed from nearby riverbeds. Fossil fauna was abundant at the BSN12 site, but cut marks or hammerstone-percussed bones were not identified.

At the DAN5 site, an elephant toe bone was found with stone tool cut marks, and a small antelope leg bone had a percussion notch, implying that H. Erectus butchered both large and small mammals, though it is not clear whether they hunted or scavenged their prey.

There is a common view that early Homo (e.g., Homo habilis) invented the first simple (Oldowan) stone tools, but when H. erectus appeared about 1.8 to 1.7 million years ago, a new stone tool technology called the Acheulian, with purposefully shaped large cutting tools such as handaxes, emerged in Africa.

The timing, causes, and nature of this significant transition to the Acheulian by about 1.7 million years ago is not entirely clear, though, and is an issue debated by archaeologists. The authors of the Science Advances paper said their investigations at DAN5 and BSN12 have clearly shown that Oldowan technology persisted much longer after the invention of the Acheulian, indicative of particular behavioral flexibility and cultural complexity practiced by H. Erectus, a trait not fully understood or appreciated in paleoanthropology.

“Although most researchers in the field consider the Acheulian to have replaced the earlier Oldowan (Mode 1) by 1.7 Ma, our research has shown that Mode 1 technology actually remained ubiquitous throughout the entire Paleolithic,” Semaw said.

“The simple view that a single hominin species is responsible for a single stone tool technology is not supported,” Rogers said. “The human evolutionary story is more complicated.” The DAN5 and BSN12 sites at Gona are among the earliest examples of H. Erectus associated with both Oldowan and Acheulian stone assemblages.

“In the almost 130 years since its initial discovery in Java, H. Erectus has been recovered from many sites across Eurasia and Africa. The new remains from the Gona study area exhibit a degree of biological diversity in Africa that had not been seen previously, notably the small size of the DAN5 cranium,” said study co-author Scott Simpson of Case Western Reserve University.

“The BSN12 partial cranium also provides evidence linking the African and eastern Asian fossils, demonstrating how successful Homo erectus was.”

In Africa, some argue that multiple hominin species may have been responsible for the two distinct contemporary stone technologies, Oldowan and Acheulian. On the contrary, the evidence from Gona suggests a lengthy and concurrent use of both Oldowan and Acheulian technologies by a single long-lived species, H. Erectus, the variable expression of which deserves continued research, according to the researchers.

“One challenge in the future will be to understand better the stone tool attributes that are likely to be passed on through cultural tradition versus others that are more likely to be reinvented by different hominin groups,” Rogers said.