What did Homo sapiens eat 170,000 years ago? Roasted, supersized land snails

Slow-motion large land snails made for easy catching and good eating as early as 170,000 years ago. Until now, the oldest evidence of Homo sapiens eating land snails dated to roughly 49,000 years ago in Africa and 36,000 years ago in Europe. But tens of thousands of years earlier, people at a southern African rock-shelter roasted these slimy, chewy — and nutritious — creepers that can grow as big as an adult’s hand, researchers report in the April 15 Quaternary Science Reviews.

Analyses of shell fragments excavated at South Africa’s Border Cave indicate that hunter-gatherers who periodically occupied the site heated large African land snails on embers and then presumably ate them, say chemist Marine Wojcieszak and colleagues. Wojcieszak, of the Royal Institute for Cultural Heritage in Brussels, studies chemical properties of archaeological sites and artifacts.

The supersized delicacy became especially popular between about 160,000 and 70,000 years ago, the researchers say. Numbers of unearthed snail shell pieces were substantially larger in sediment layers dating to that time period.

New discoveries at Border Cave challenge an influential idea that human groups did not make land snails and other small game a big part of their diet until the last Ice Age waned around 15,000 to 10,000 years ago, Wojcieszak says.

Long before that, hunter-gatherer groups in southern Africa roamed the countryside collecting large land snails to bring back to Border Cave for themselves and to share with others, the team contends. Some of the group members who stayed behind on snail-gathering forays may have had limited mobility due to age or injury, the researchers suspect.

“The easy-to-eat, fatty protein of snails would have been an important food for the elderly and small children, who are less able to chew hard foods,” Wojcieszak says. “Food sharing [at Border Cave] shows that cooperative social behavior was in place from the dawn of our species.”

Border Cave’s ancient snail scarfers also push back the human consumption of mollusks by several thousand years, says archaeologist Antonieta Jerardino of the University of South Africa in Pretoria. Previous excavations at a cave on South Africa’s southern tip found evidence of humans eating mussels, limpets and other marine mollusks as early as around 164,000 years ago (SN: 7/29/11).

Given the nutritional value of large land snails, an earlier argument that it was eating fish and shellfish that energized human brain evolution may have been overstated, says Jerardino, who did not participate in the new study.

It’s not surprising that ancient H. sapiens recognized the nutritional value of land snails and occasionally cooked and ate them by 170,000 years ago, says Teresa Steele, an archaeologist at the University of California, Davis who was not part of the work. But intensive consumption of these snails starting around 160,000 years ago is unexpected and raises questions about whether climate and habitat changes may have reduced the availability of other foods, Steele says.

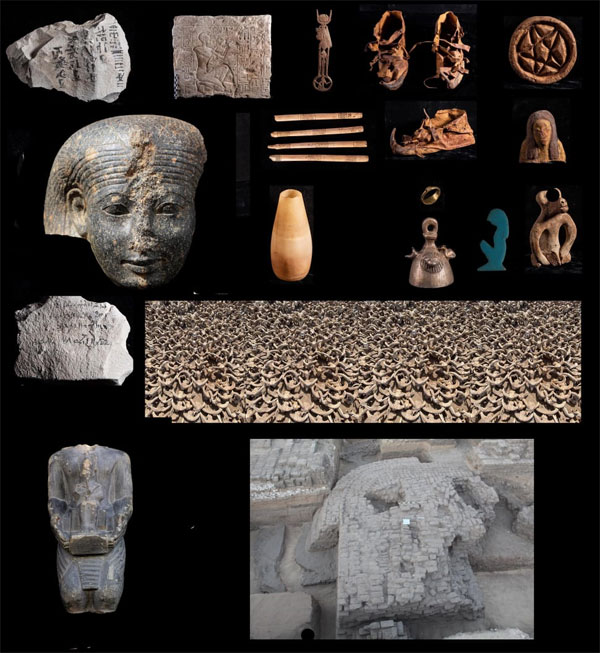

Researchers have already found evidence that ancient people at Border Cave cooked starchy plant stems, ate an array of fruits and hunted small and large animals. The oldest known grass bedding, from around 200,000 years ago, has also been unearthed at Border Cave (SN: 8/13/20).

Several excavations have been conducted at the site since 1934. Three archaeologists on the new study — Lucinda Backwell and Lyn Wadley of Wits University in Johannesburg and Francesco d’Errico of the University of Bordeaux in France — directed the latest Border Cave dig, which ran from 2015 through 2019.

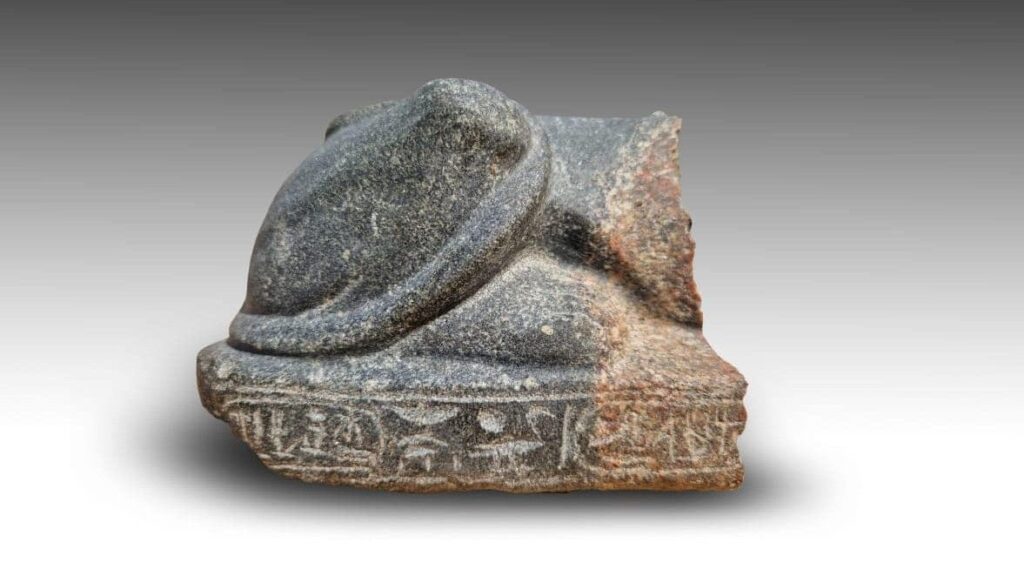

Discoveries by that team inspired the new investigation. Excavations uncovered shell fragments of large land snails, many discolored from possible burning, in all but the oldest sediment layers containing remnants of campfires and other H. sapiens activity. The oldest layers date to at least 227,000 years ago.

Chemical and microscopic characteristics of 27 snail shell fragments from various sediment layers were compared with shell fragments of modern large African snails that were heated in a metal furnace. Experimental temperatures ranged from 200° to 550° Celsius. Heating times lasted from five minutes to 36 hours.

All but a few ancient shell pieces displayed signs of extended heat exposure consistent with having once been attached to snails that were cooked on hot embers. Heating clues on shell surfaces included microscopic cracks and a dull finish.

Only lower parts of large land snail shells would have rested against embers during cooking, possibly explaining the mix of burned and unburned shell fragments unearthed at Border Cave, the researchers say.