Rare 2,800-Year-Old Assyrian Scarab Amulet Found In Lower Galilee

Erez Avrahamov, a 45-year-old inhabitant of Peduel, made an incredible discovery while hiking in the Tabor Stream Nature Reserve located in Lower Galilee. He stumbled upon an ancient seal shaped like a scarab that dates back to the First Temple period.

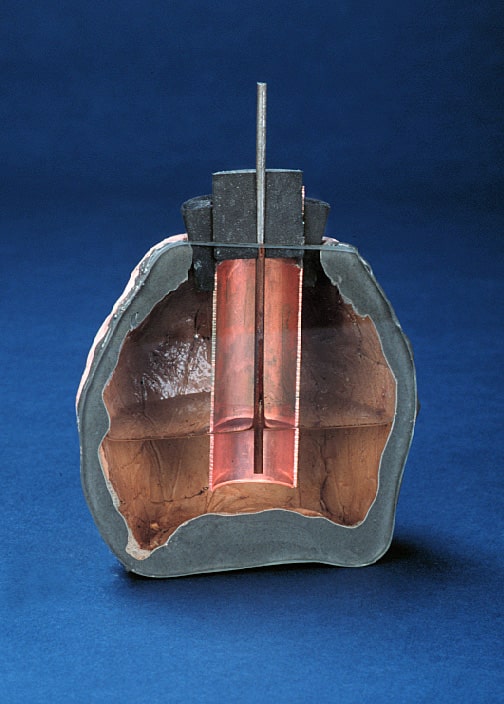

This ancient artifact is as unique as it is stunning. Avrahamov initially mistook it for a bead or an orange stone lying on the ground. However, upon closer inspection, he realized it was intricately engraved, resembling a scarab or beetle.

Recognizing its potential significance, Avrahamov promptly contacted the Israel Antiquities Authority to report this extraordinary discovery.

Nir Distelfeld, an Inspector from the Antiquities Robbery Prevention Unit of the Israel Antiquities Authority, swiftly realized Avrahamov had stumbled upon something extraordinary. He instructed him to carefully examine the other side of the scarab – the flat side – to see if it bore any engravings.

The scarab, an ancient sacred symbol, has a rich history that dates back to the late Paleolithic era when beetle-shaped ornaments were common. By the time of Egypt’s Old Kingdom in the 3rd millennium B.C., scarabs had evolved into aesthetically pleasing objects with deep shamanic symbolism. They played a significant role in early animal worship.

The Egyptian name derives from the verb “to become” or “to be created”, as the Egyptians saw the scarab as a symbol of the creator god. This is corroborated by archaeological findings from King Den’s reign during Dynasty I.

Just as Christians revere the cross today, Egyptian pharaohs profoundly respect dung beetles – likely viewing them as sacred symbols.

”The scarab, made of a semi-precious stone called carnelian, depicts either a mythical griffin creature or a galloping winged horse. Similar scarabs have been dated to the 8th century BCE.” Distelfeld adds that, “the beautiful scarab was found at the foot of Tel Rekhesh, one of the most important tells in Galilee.

The site has been identified as ‘Anaharat’, a town within the territory of the tribe of Issachar (Joshua 19:19),” Professor Emeritus Othmar Keel of the University of Fribourg, Switzerland explained.

Scarabs were crafted from various stones, including semi-precious ones like amethyst and carnelian. However, most were made from steatite – a soft talc stone with a grayish-white hue, typically coated with a blue-green glaze. This glaze could only withstand dry climates like Egypt’s.

Hence, scarabs discovered in Israel seldom show remnants of it. This particular scarab’s deep orange color is uncommon and visually captivating in this scenario.

According to Dr. Itzik Paz, an Israel Antiquities Authority archaeologist who excavated at Tel Rekhesh, the discovery of this significant artifact from Tel Rekhesh, dating back to the Iron Age (7th–6th centuries BCE), is truly noteworthy.

During this period, a large fortress was present on the tell, seemingly under Assyrian rule – the same empire that led to the downfall of the Northern Kingdom of Israel.

The scarab found at the base of the tell could potentially indicate an Assyrian (or maybe even Babylonian) administrative presence at that location.

The griffin design on the seal is a recognized theme in ancient Near Eastern art and frequently appears on Iron Age seals. If we can accurately date this seal, it might provide a direct connection to Assyrian influence in the Tel Rekhesh fortress – an incredibly significant find!