One of its kind, 1,500-year-old Roman ‘Lorica Squamata’ legion armor restored

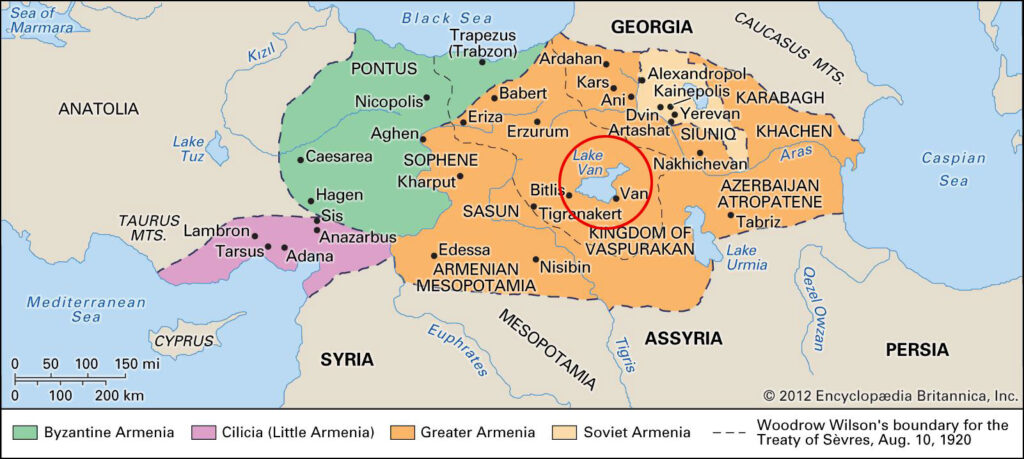

The 1,500-year-old Roman ‘Lorica Squamata’ legion armor, the only known example in the world, found in the ancient city of Satala in the village of Sadak in the Kelkit district of Gümüşhane in the Black Sea region of Türkiye, was restored.

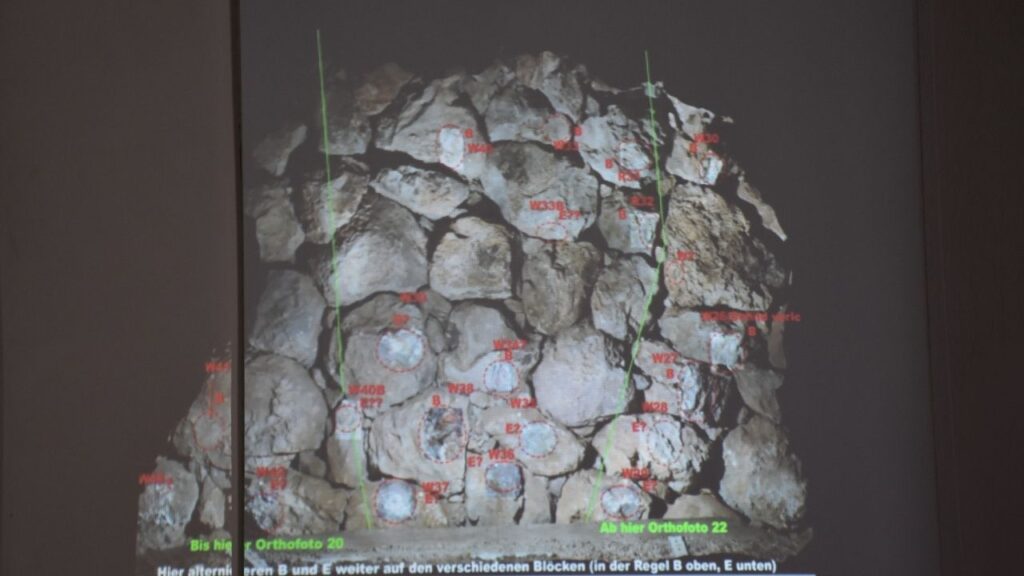

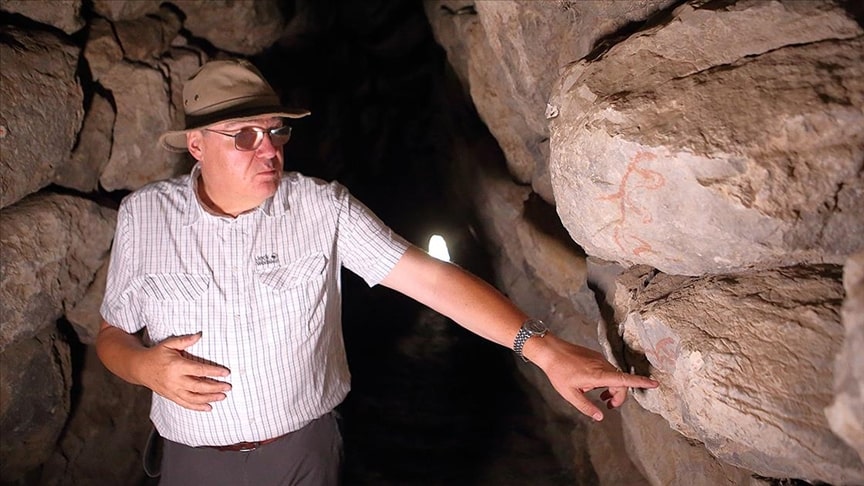

Archaeological excavations continue in the ancient city of Satala, the only surviving castle on the eastern border of the Roman Empire and the only Roman Legion castle in Anatolia that can be excavated. and this unique artifact was unearthed during the 2020 excavation season.

The ancient city of Satala, where the 15th Legion of the Roman Empire, also known as the Apollinaris Legion, ruled for 600 years, is a well-known castle visited by Rome’s five emperors.

In a remarkable feat of preservation, the only known example of a “Lorica Squamata” model Roman legionary armor, dating back 1,500 years, has been successfully restored in Türkiye.

The completion of the restoration was announced by the Turkish Ministry of Culture and Tourism on its social media account.

The armor was first found and removed from the location in 2021 with assistance from the Ankara Regional Laboratory.

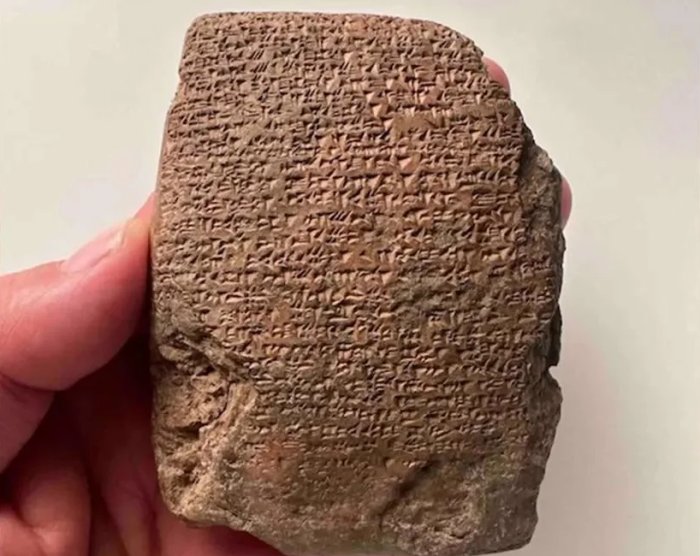

It was then moved to the Erzurum Restoration and Conservation Regional Laboratory. Erzurum Atatürk University carried out a thorough examination, which included tomography and X-rays, to record the armor in its soil-encrusted state.

X-ray results revealed that almost the entire armor was intact. Micro CT imaging of a three-plate block taken from the edges helped determine the armor’s full measurements and partial metallurgical properties.

The conservation and restoration procedures were finished after three years of painstaking labor by the Erzurum Regional Directorate of Restoration and Conservation Laboratory. The armor was then resewn, returning it to its original form.

According to the ministry’s statement, the armor dates back to the Late Roman Period. It is a significant example of the Lorica Squamata type, noted for being the first known to the world.

During the Roman era, legionary armor was not made to order; instead, it was repaired and reused as needed. Surviving examples are extremely rare these days because, once damaged beyond repair, they were melted down and used for new purposes.

During the height of the Roman Empire, the Lorica Squamata was a common type of armor worn by military officers and specialists such as musicians or standard bearers. In certain provinces, it may have also been used to outfit entire regiments of Auxilia infantry, archers, and cavalrymen. Later in the Empire’s history, troops frequently used scaled armor as a form of protection.

Scaled Armor was very difficult to cut through and offered a strong, reliable defense for the wearer. In addition, the armor’s overlapping scales provided some absorptive qualities against concussive force. Usually, the scales were between.5 and.8 mm thick to keep the armor’s total weight under control.

Highlighting the achievement, Turkish Culture and Tourism Minister Mehmet Nuri Ersoy said: “The ‘Lorica Squamata’ model armor, revived by expert hands at the Erzurum Regional Directorate of Restoration and Conservation Laboratory, has reached us almost perfectly preserved.”