Drowned Stone Age fishermen were examined with a forensic method that could rewrite prehistory

Human bones dating to the Stone Age found in what is now northern Chile are the remains of a fisherman who died by drowning, scientists have discovered.

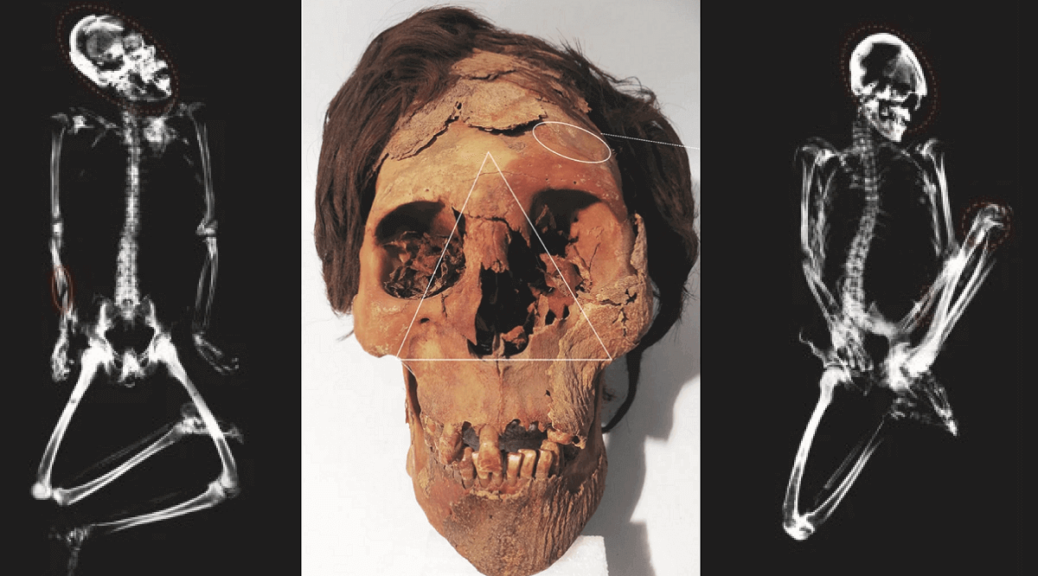

The man lived about 5,000 years ago, and he was around 35 to 45 years old when he died. Scientists found the skeleton in a mass burial in the coastal region of Copaca near the Atacama Desert, and the grave held four individuals: three adults (two males and one female) and one child.

The man would have been about 5 feet, 3 inches (1.6 meters) tall when alive, and his remains showed signs of degenerative diseases and metabolic stress, researchers reported in the April 2022 issue of the Journal of Archaeological Science.

The bones revealed traces of osteoarthritis in his back and both elbows; the back of his skull had evidence of healed injuries from blunt trauma; his teeth and jaws were marred by tartar, periodontal disease and abscesses; and lesions in his eye sockets hinted at an iron deficiency caused by ingesting a parasite found in marine animals, according to the study.

Other marks on the arm and leg bones where muscles were once attached told of repetitive activities related to fishing, such as rowing, harpooning and squatting to harvest shellfish. If the individual was a fisherman, perhaps he died by drowning, the researchers proposed.

When forensic teams examine modern skeletons that were found without any soft tissue attached, experts can confirm drowning as the cause of death by looking inside large bones for delicate microscopic algae, called diatoms, which live in watery habitats and soil.

When a person drowns, inhaled water can enter the bloodstream and travel throughout the body after the lungs rupture, even reaching the “closed system” of bone marrow through capillaries, the authors reported. Looking at diatom species in bone marrow can thereby reveal if the person ingested saltwater. However, this method had never been used to examine ancient bones.

Algae, sponge spines and parasitic eggs

For the new study, the scientists decided that the modern diatom test was too “chemically aggressive,” and in removing bone marrow from samples, it also destroyed small particles and organisms that weren’t diatoms. Such particles could be highly significant for analyzing Stone Age bones, according to the study.

The researchers, therefore, adopted “a less aggressive process” that eliminated residual bone marrow in their samples, while preserving a wider range of microscopic material absorbed by the marrow, which could then be detected by scanning electron microscopy (SEM).

Their SEM scans revealed a microorganism jackpot. While there was no marine material clinging to the outside of the bones, the scans showed that the marrow contained plenty of tiny ocean fossils, including algae, parasitic eggs and broken sponge structures called spicules. This variety of marine life deep inside the man’s bones suggests that he died by drowning in saltwater.

It’s possible that the cause of death was a natural disaster, as the geologic record in this coastal region of Chile preserves evidence of powerful tsunamis dating to around 5,000 years ago, the scientists reported. But with ample skeletal evidence that the person was a fisherman, the more likely explanation is that he died during a fishing accident, they said.

Damage to the skeleton — missing shoulder joints, cervical vertebrae that were replaced with shells and a broken ribcage — could have happened when waves pummeled the drowned man’s body and then washed it ashore, the researchers explained.

As to why the man was buried in a mass grave, “what we can assess from similar contexts is that they probably belonged to the same family group,” said lead study author Pedro Andrade, an archaeologist and a professor of anthropology at the University of Concepción in Chile.

The individuals likely shared an ancestor but weren’t immediate family members, as the dates of the skeletons spanned about 100 years, Andrade told Live Science in an email.

By expanding the range of the modern diatom test to include a broader selection of microscopic marine life in their search through the interior cavities of prehistoric bones, “we’ve cracked open a whole new way to do things,” study co-author James Goff, a visiting professor in the School of Ocean and Earth Science at the University of Southampton in the United Kingdom, said in a statement.

“This can help us understand much more about how tough it was living by the coast in prehistoric days — and how people there were affected by catastrophic events, just as we are today,” Goff said.

Applying this method across other archaeological sites in coastal areas with mass graves could offer game-changing insight into how ancient people survived — and often died — while living under potentially perilous conditions, Andrade told Live Science.

While there are many coastal mass burial sites worldwide that have been investigated by scientists, “the fundamental question of what caused so many deaths has not been addressed,” Goff added.