A Massive, Black Sarcophagus Has Been Unearthed in Egypt, And Nobody Knows Who’s Inside

Archaeological digs around ancient Egyptian sites still have plenty of secrets to give up yet – like the huge, black granite sarcophagus just discovered at an excavation in the city of Alexandria, on the northern coast of Egypt.

What really stands out about the solemn-looking coffin is its size. At 185 cm (72.8 inches) tall, 265 cm (104.3 inches) long, and 165 cm (65 inches) wide, it’s the biggest ever found in Alexandria.

Oh, and then there’s the large alabaster head discovered in the same underground tomb. Experts are assuming it represents whoever is buried in the sarcophagus, though that’s yet to be confirmed.

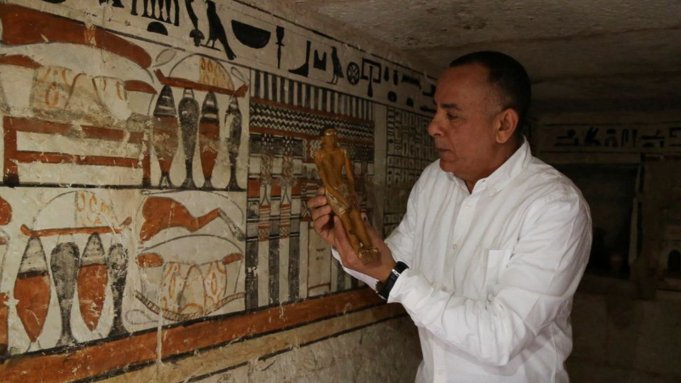

It’s a fascinating find for archaeologists. Ayman Ashmawy from the Egypt Ministry of Antiquities says the layer of mortar still intact between the lid and the body of the coffin indicates it hasn’t been opened since it was sealed more than 2,000 years ago.

That’s particularly rare for a site like this – ancient Egyptian tombs have often been plundered and damaged over the centuries, which means archaeologists rarely find a final resting place that’s still intact like this one appears to be.

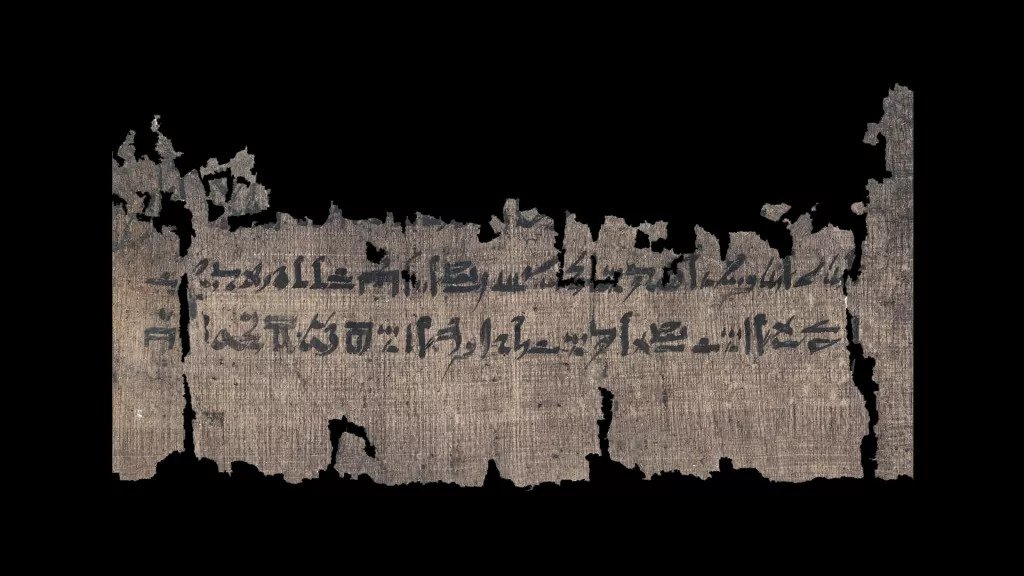

The site as a whole dates back to the Ptolemaic period between 305 BCE and 30 BCE, with this particular, find uncovered five meters (16.4 feet) below the ground.

Originally found while clearing the site for a new building, the tomb is now under guard while experts can work out what exactly lies inside the black sarcophagus. It could almost be the start of a new Indiana Jones film.

As Jason Daley at the Smithsonian reports, down the centuries Alexandria has developed to be such a busy, crowded city that finding relics can be a challenge – anything that has managed to survive is often difficult to get to.

Those are all the details we have of the new find, so we’ll have to wait and see if the identity of the buried Egyptian can be determined. But a sarcophagus of this size could mean someone of pretty high status.

We haven’t been short of incredible finds in Egypt this year.

In February, archaeologists found a hidden network of tombs south of Cairo in the Minya Governorate, which – like the giant granite sarcophagus – have probably lain untouched for 2,000 years. Experts say it’ll take them five years to work through that site.

Then in April, a rare Greco-Roman temple was found. It promises to reveal secrets about the Siwa Oasis, one of the most remote settlements in Egypt, including how foreign rule affected the country between 200-300 BCE.

Every discovery paints a little more detail about how people lived and worked in these ancient times. We’ll be keeping a close eye on this sarcophagus to see what it might reveal.