85 ancient tombs unearthed in Egypt

A total of 85 tombs, dating back to the period from the Old Kingdom of Egypt some 4,500 years ago until the Ptolemaic dynasty spanning from 305 BC to 30 BC, were unearthed in the southern province of Sohag, the Ministry of Tourism and Antiquities said.

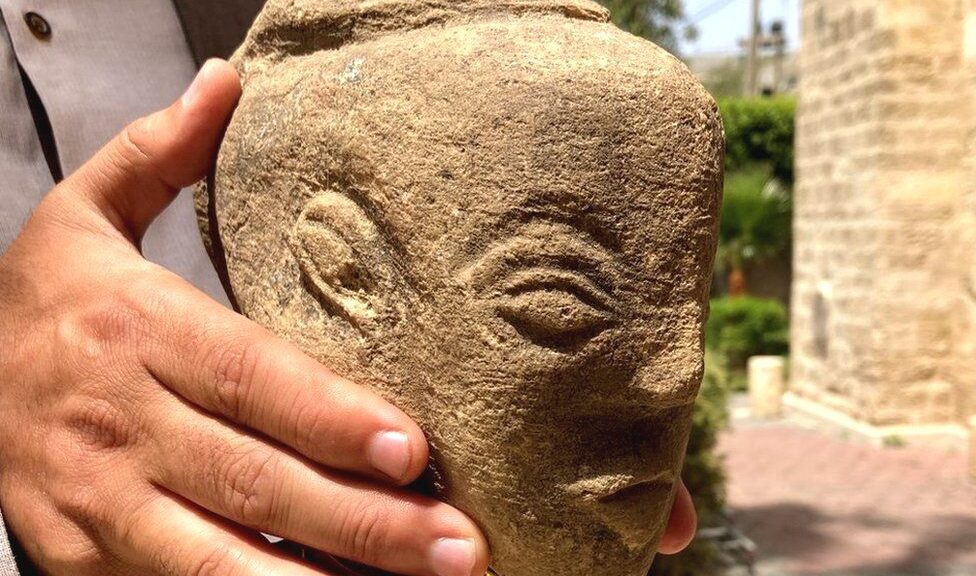

The remains of many mummies have been found inside these tombs, which span an impressive range of time. The earliest burials contain the remains of people who lived in Egypt’s Old Kingdom 4,500 years ago, while the most recent can be traced to the era of the Ptolemaic dynasty, the Hellenistic kingdom that ruled the nation from 305 to 30 BC.

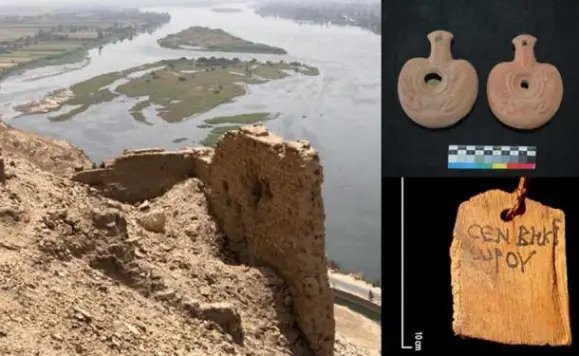

This noteworthy discovery was made by an archaeological mission from Egypt’s Supreme Council for Antiquity, which had been dispatched to the Gabal El Haridi region about 220 miles (350 kilometres) south of Cairo.

The Amazing Artifacts Of The New Egyptian Tomb Area

This is not the first archaeological mission to be deployed in this area. However, the scope of what the archaeologists discovered, 85 new Egyptian tombs spanning nearly 2,500 years of history, has made this one of the more dramatic excavation seasons at Gabal El Haridi in recent memory.

In addition to the mummies they found, the archaeologists also recovered approximately 30 written certificates from inside the tombs that contained personal information about the deceased. These funerary permits included the dead individual’s name, parents’ names, age, and occupation. The information was written in Greek, but some of the permits also included Egyptian hieroglyphics that offered prayers to ancient Egyptian gods.

Many of the new Egyptian tombs unearthed at Gabal El Haridi were dug into the side of a local mountain. Some of the more elaborate tombs had one or more wells that had corridors leading to burial rooms.

Along with the 85 new Egyptian tombs, the archaeologists also uncovered the ruins of a sturdy tower house made from mudbrick. This imposing edifice was constructed during the reign of King Ptolemy III, who served as the third pharaoh of the Ptolemaic line. He ruled Egypt for 24 years, from 246 to 222 BC, under the auspices of a dynasty that was established in 305 BC by its first king Ptolemy I Soter, a Macedonian general who was a close confidant of Alexander the Great.

The tower house was an official structure of the government and would have served as a combination checkpoint and surveillance post. Government functionaries stationed at the tower house would have been responsible for monitoring the comings and goings of people passing over the border, by boat on the Nile River or by foot. They would have also collected taxes from travellers and merchants, plus insurance payments from the owners of ships sailing on the Nile.

The Egyptian archaeological mission also reported on their continued excavation of a Ptolemaic-era temple dedicated to the goddess Isis. In its time the temple would have been extravagant and impressive, not to mention gigantic. It was 450 long and 650 feet wide (140 by 200 meters) when first constructed, with an interior that featured thick columns and large gathering halls. Among the relics found inside the temple were 38 coins from the Roman era, and animal bones that revealed information about the diet of temple priests.

The ruins of the ancient Isis temple were originally discovered during previous excavations at the Gabal El Haridi site. More and more of the buried building has been slowly revealed over the past few years, and archaeologists continue to be impressed by the size and span of this massive religious shrine that was built for worshippers of ancient Egypt’s most famous goddess.

Another noteworthy find during the most recent digs was a house that once belonged to a supervisor of workers. Among the ruins of this structure, the archaeologists salvaged the paper remains of some worker records, which included these individuals’ names, job duties, and salaries. This type of data is highly treasured by historical researchers since it gives them valuable insights into how average people lived long ago.

In Egypt, an Archaeologist’s Job is Never Finished

The archaeologists from the latest Supreme Council mission to Gabal El Haridi have found many important ruins and relics connected to the Ptolemaic dynasty period in particular. This transformational time in Egyptian history saw the nation develop one of the most substantial centres of Greek culture in the ancient world. This represents a remarkable evolution, given everything Egyptians accomplished within the boundaries of their own distinctive culture.

Egypt’s history is colourful and cosmopolitan, and because the land is so rich in ancient artefacts it is a history the world has gotten to know quite well.

No matter how long archaeologists keep digging in Egypt, they keep finding fantastic reminders of the country’s ancient glory. The Gabal El Haridi region in Sohag is just one of many sites that have produced a treasure trove of revealing ruins from an ancient culture that continues to fascinate the world.